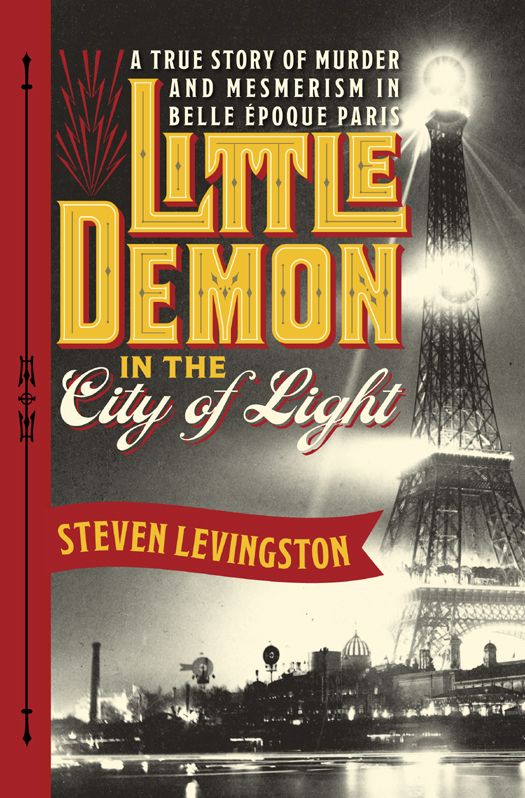

Little Demon in the City of Light: A True Story of Murder and Mesmerism in Belle Epoque Paris

Authors: Steven Levingston

Copyright © 2014 by Steven Levingston

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

DOUBLEDAY

and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Book design by Maria Carella

Jacket design by Roberto de Vicq de Cumptich

Eiffel Tower photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress,

Prints and Photographs Division

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Levingston, Steven.

Little demon in the city of light: a true story of murder and mesmerism in Belle Époque Paris / Steven Levingston.—First edition.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Murder—France—Paris—Case studies. 2. Gouffé, Toussaint-Augustin, 1840–1889. 3. Eyraud, Michel, 1843–1891. 4. Bompard, Gabrielle, 1868–1920. 5. Paris (France)—Social life and customs—19th century.

I. Title.

HV6535.F8P364 2014

364.152′3092—dc23

2013020525

ISBN 978-0-385-53603-5

eBook ISBN 978-0-385-53604-2

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

v3.1

FOR SUZANNE, KATIE, AND BEN

The experiments were chilling. In one, a woman was hypnotized and ordered to shoot a local government official. When handed a gun, she walked directly up to him and pulled the trigger, firing a blank she imagined was a real bullet. After the official—playing along—fell to the floor, she stood calmly over him hallucinating that he was dying in a pool of blood. Under interrogation she admitted to the crime with utter indifference, parroting what the hypnotist-researcher had planted in her head: that she simply didn’t like the man. In another experiment, a hypnotized woman was told to dissolve a white powder she believed was arsenic in a glass of water and offer it to a man nearby. If anyone were to ask, she was to say the glass contained sugar water. She did exactly as she was told, and the man quaffed the tainted drink. After she was brought out of her trance, she dutifully followed the hypnotist’s final command: She told her interrogator that she didn’t remember a thing; she hadn’t given a drink to anyone. Most disturbing, she couldn’t name anyone who had directed her to do anything.

In the late nineteenth century, doctors, scientists, and professors were desperate to answer an alarming question: Could a person be persuaded under hypnosis to commit a terrible crime, even murder? At risk was the very foundation of law and order. If researchers discovered that hypnotic crime was possible, then who was safe? Thievery, assault, arson, and murder—secretly directed by evil hypnotists—became nightmarish possibilities. And what if a madman launched an army of hypnotized automatons on a presidential palace? Revolution was not out of the question.

In the Paris of the 1880s, the setting for our tale, hypnosis was in its heyday. Doctors had corralled its mysterious powers to treat

a range of complaints. In medical clinics, doctors softly encouraged their patients:

“Look at me. Think of nothing but sleep … sleep. Your lids are closing. Your arms feel heavy. You are going to sleep … sleep … sleep.” While concentrating on the doctor’s voice, the patient stared at a bright light, or gazed into his eyes, or watched his hands pass several times in front of her face until she drifted off. When she left the clinic, she was free of back pain, or menstrual cramps, or chronic headaches.

Hypnotism was an ornament of the city’s daily life. Society ladies, demonstrating that they were au courant, hosted hypnotism salons. Amateurs learned the techniques and threw their friends into trances. Traveling hypnotists wowed audiences with astonishing stage shows. The famous traveling hypnotist Professor Donato put his bejeweled assistant through the human-plank trick, in which she would lie between two chairs stiff as a board, defying gravity. He hypnotized audience volunteers and had them disrobe to their underclothing and dance in imaginary ponds and bite into potatoes that they believed were apples. Europeans delighted in the cures and the endless amusement. But the excitement was tinged with fear. No one really knew how powerful hypnosis was, and whether or not it could lend itself to nefarious uses. Courts already had ruled on a few instances of hypnosis-assisted rape. In one notorious case in 1879, a dentist in Rouen was sentenced to ten years in prison for having sex with a twenty-year-old patient he had hypnotized in the dental chair. No court, however, had yet seen a case in which an accused murderer blamed a hypnotist for his crime. That was about to change.

The belle époque, stretching from 1871 to the start of World War I in 1914, is remembered for its pleasures and eccentricities, but it was also a time of magnificent ambition and spectacle and unrelenting dread. The Eiffel Tower went up on the Champ de Mars in 1889, at the time the tallest man-made structure in the world, and served as the centerpiece of the Paris International Exposition, then the largest world’s fair in history. Paris was a stage, and its inhabitants were actors, dressed for show and behaving outrageously. There was the theatrical star Sarah Bernhardt, who kept a pet tiger and slept with a coffin at the foot of her bed. There were the throngs who strolled past the recently dead at the Paris morgue as if viewing a museum exhibit; the French had a weakness for the macabre, which Sigmund Freud, a

young, cocaine-dependent medical student discovered as he explored the city. At night, bizarre indulgences awaited in the music and dance halls: At the Folies-Bergère there was a boxing match between a man and a kangaroo, and at the Moulin Rouge a sidesplitting act by a vaudevillian in a red silk coat and white butterfly tie, who sang “Au clair de la lune” through his anus.

Although the period before World War I was an era of champagne bubbles, men in top hats and monocles, and carefree strolls along the boulevards, it was not the golden age people wished to remember years after the carnage. As the historian Barbara Tuchman put it,

“It was not a time exclusively of confidence, innocence, comfort, stability, security and peace. Our misconception lies in assuming that doubt and fear, ferment, protest, violence and hate were not equally present.”

Hypnotism reflected not only the era’s giddiness but also the unease. France’s Republican government was fragile, anarchist rage was brewing, syphilis mercilessly attacked the well-born and the underclass alike. Newspapers sensationalized the bloodiest crimes; in some neighborhoods, people went to bed worrying that teenage thugs would slash their throats while they slept. Parisians looked upon the present with uncertainty and gazed toward the new century with a fear that their glorious nation was sliding into degeneracy. Crime under hypnosis added to French anxieties about the fragility of modern life. But just how serious a danger it posed was a matter of intense debate.

A battle raged between two opposing camps, one based in Paris, the other some two hundred and forty miles east in the city of Nancy. Comforting assurances came from the world’s foremost neurologist, Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot, and his disciples at the Salpêtrière Hospital in the thirteenth arrondissement. The forbidding Charcot, described as

“half-Dante, half-Napoleon,” had a smooth beardless face, deep-set dark eyes, and long hair combed back over his head. He asserted that the outcries over hypnotic crime were exaggerated: An individual in a trance could not be coerced into abandoning her moral resolve and led into deviant behavior. Charcot’s research revealed that there were limits to what a hypnotized person would do—dancing like a silly drunk was one thing, murder quite another.

Charcot had bestowed upon hypnotism a new respectability, rescuing

it from the scientific hinterlands. Most scientists had denied legitimacy to hypnotism for a hundred years after the early practitioner Dr. Franz Anton Mesmer destroyed its credibility with his wild claims of medical success. Mesmer was a brilliant eccentric who dressed in a lilac silk coat and believed that a universal magnetic fluid flowed through everything, pulling on the tides, on human blood, on the nerves, and that he could heal suffering by controlling the magnetic currents inside his patients. His powerful personality attracted a passionate following; and his influence was so profound that hypnosis is still sometimes called mesmerism. His claims of curing epilepsy, paralysis, and even blindness were ultimately insupportable, however, and he died alone in disrepute, his only companion being his pet canary which, according to rumor, had been trained to drop lumps of sugar into his coffee.

Only a scientist of unassailable credentials could have healed the wounds Mesmer inflicted on hypnotism, and now Charcot’s doctrines on the science of hypnosis were accepted as dogma throughout Europe. But on the question of hypnotic crime, he faced a challenge. Professors at the University of Nancy were undaunted by his authority or by the sovereignty of Paris. Among their ranks was the leading expert on hypnotic crime, a professor of law named Jules Liégeois who had poured his findings into a seminal book on the subject in 1884. His conclusions left no doubt about where he stood. A hypnotized individual, in Liégeois’s view, lost her faculties of reason, judgment, morality, and will and became

“the plaything of a fixed idea,” in essence, an automaton acting at the whim of the hypnotist. In such a state, she would carry out a criminal suggestion unhesitatingly and then forget who had placed the notion in her head. The hypnotic subject in Liégeois’s scenario is no more culpable than a pistol or knife; the responsible party is the hypnotist who used this human weapon to carry out his evil deed.

“All conscience has disappeared in a hypnotized subject who has been forced to commit a criminal act,” Liégeois asserted. “Only he who has given the suggestion is guilty, and only he should be pursued and punished.”