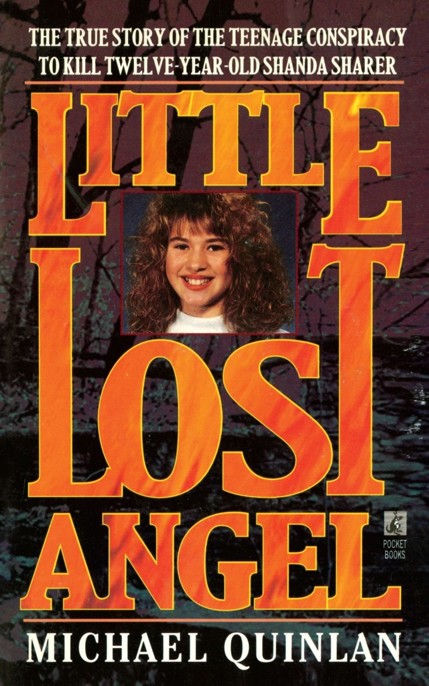

Little Lost Angel

Thank you for purchasing this Pocket Books eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Pocket Books and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Epilogue

Photographs

For Jacque and Steve

and in memory of

Shanda

Many people deserve my thanks but none more than Detective Steve Henry and Prosecutor Guy Townsend. Their graciousness never wavered during my lengthy interviews and my dozens of phone calls to their homes and offices.

My appreciation to Judge Ted Todd and his staff, especially Jenny Redwine. Thanks to Sheriff Buck Shipley, Sgt. Curtis Wells, Deputy Randy Spry,

Madison Courier

reporter Wayne Engle, photographer Joe Trotter, and attorneys Russ Johnson, Wil Goering, and Bob Donald. Also thanks to Donn Foley, Marc Botts, and everyone else who helped me gather the facts, and to Eileen and Mike for their computer help.

At the

Louisville Courier-Journal

, thanks to editors Hunt Helm and Karen Merk, reporters Pam Runquist and David Goetz, and the photo and library staffs.

Thanks to my literary agent, Ann Rittenberg, and my editors at Pocket Books, Claire Zion and Amy Einhorn, for guiding me through uncharted waters.

And thanks to my family for their love and support.

Most of all, thanks to Jacque and Steve and the rest of Shanda’s family for sharing their memories and friendship.

This is a true story. In order to tell it in narrative form I re-created some dialogue and descriptive details from my interviews with one or more of the people involved or from police reports, depositions, and court testimonies.

All of the names, places, dates, and events in this book are real.

Jealousy is cruel as the grave; the coals thereof are coals for fire, which hath a most vehement flame.

—Song of Solomon 8:6, Old Testament

U

nder cover of darkness, the blood-stained sedan moved slowly along the narrow, winding roads of the southern Indiana countryside. With each turn the car’s headlights threw a momentary flash of illumination through a black forest of pines, hickories, and elms. The silence of the cold winter night was marred by the constant growl of the sedan’s broken tailpipe.

As a pair of headlights approached from the other direction, the driver let up on the gas, easing the tailpipe’s rumble. It might be a police car, and they couldn’t take the chance of being stopped for a noisy muffler. A nosy cop might notice the scarlet handprints on the trunk or find the bloody tire iron lying under the seat. Holding their breath, the driver and front-seat passenger watched the car pass them by. The driver’s steely eyes shifted to the rear-view mirror, following the car’s tail lights until they disappeared over a hill.

The sedan picked up speed as it passed through a small town with the biblical name of Canaan, then entered the woods again and drove deeper into the darkness. They drove for hours, searching the edges of the road for a place

to dump the body of the twelve-year-old girl locked in the trunk.

Tired of arguing, they traveled now in silence. The driver, a hard-edged blonde, had wanted to throw the body off a bridge into a creek. But the passenger, a slim brunette, had called the driver a fool. “Don’t you know she’ll float.”

They were far from Canaan, in a stretch of deep woods, when they heard a noise barely audible over the tailpipe’s roar, a soft thumping coming from the trunk.

The blonde stopped the car in the middle of the road and left the engine idling. She pulled the trunk key from the key chain and reached under the seat for the tire iron, then stepped out into the cold air. She instructed the brunette to slide over behind the steering wheel. “Rev it,” she said, “in case she screams again.”

The blonde walked stiffly, purposefully, to the rear of the car and opened the trunk where Shanda Sharer lay imprisoned, still clinging to life.

S

handa Sharer’s normally neat bedroom was in disarray.

The closet door hung open, and skirts, blouses, and jeans were strewn about. A cassette tape of Mariah Carey blared in the background as the twelve-year-old primped in front of her mirror, studying her latest outfit from every angle. After three years of drab Catholic school uniforms, she was in a tizzy deciding what to wear the next day—her first day at Hazelwood Junior High.

“Ta-da!” Shanda announced as she slowly descended the stairway, mimicking the elegant style of a Paris fashion model.

Jacque Ott turned her attention from the television and smiled in appreciation at her daughter, something she’d done a dozen times that night. “That’s it. I like that one best,” she said with a hint of finality, hoping her daughter would get the point. The modeling had dragged on for hours, and Jacque was eager for Shanda to go to bed.

“Me too,” Shanda said with a sigh, relieved to have finally settled on the perfect ensemble for her debut into Hazelwood society.

Putting things away wasn’t nearly as much fun as getting

them out. Exhausted, Shanda flopped onto her bed and reached for her diary.

“Well, this year I’m going to a different school,” she wrote. “I’m sort of scared I won’t fit in because I heard that there were hoods, pretty girls, and ‘all-that’ guys. I wish my mom would understand that I don’t want to be twelve. I want to be thirteen. I wish I could tell everyone at Hazelwood I’m thirteen but I know my mom won’t go along with it.”

Shanda could easily have pulled off such a charade. She’d just celebrated her twelfth birthday that June and was already losing the awkwardness of adolescence. She had a trim, athletic figure, long blond hair, dark eyebrows, wide hazel eyes, and a dimpled smile. These pleasant attributes had not gone unnoticed by the boys at her previous school, St. Paul Catholic. They’d flirted with all their young charms and she’d enjoyed the attention, often giggling about the young Romeos with her girlfriends.

But that seemed so long ago now. She and her mother had moved across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky, to the small town of New Albany, Indiana, and tomorrow she would walk into an unfamiliar school filled with unfamiliar faces. Through her uncertainty, Shanda clung to the thought that her life would be so much easier if she were only a little older.

“I love my mom very much but she doesn’t understand how much I want to be thirteen and have people spend the night on school nights,” Shanda wrote. “I can’t talk on the phone past ten. At everybody else’s house I can but not here. I love my mom but sometimes she doesn’t understand. But I still love her!!!!!!”

Shanda had slipped the diary under her bed and was snuggled beneath the covers when Jacque entered the room and sat down beside her. For what must have been the tenth time that day, Shanda lamented, “I don’t know anybody at Hazelwood.” Then she asked the usual follow-up question: “Mom, do you think everybody will like me?”

Shanda was exaggerating a bit when she said she wouldn’t know anyone. Her cousin Amanda Edrington went to Hazelwood,

and just the day before Shanda had met a girl in the neighborhood, Kristie Farnsley, who was also starting the seventh grade there.

“You’ll meet friends just like you did at St. Paul,” Jacque assured her. “You’ve never had any problem making friends. You know that.”

The comforting words seemed to ease Shanda’s worries. Jacque didn’t let on that she too had reservations about Hazelwood Junior High.

Shanda had thrived at St. Paul, where she’d made good grades, had many friends, and participated in cheerleading, volleyball, gymnastics, 4H, and Girl Scouts. But Jacque worried that Shanda would be lost in the crowd at Hazelwood, which had twice as many students in just the seventh and eighth grades than St. Paul had in the entire school. She’d wanted to enroll Shanda at Our Lady of Perpetual Help in New Albany, but the tuition was more than she could afford. She’d just gotten divorced—for the third time—and money was scarce.

Jacque’s first marriage had been to her high-school sweetheart, Mike Boardman. Their marriage had lasted only two years after their daughter, Paije, was born. Her second marriage had been to Shanda’s father, Steve Sharer, and she still thought of her early years with Steve as the best times of her life. But that marriage too had ended in failure.

Shanda was seven when Jacque had married Ronnie Ott, who, at forty-one, was ten years older than Jacque and offered the financial security that she felt she and her two daughters needed. That marriage had fallen apart after four years, and now Jacque, an attractive thirty-six-year-old blonde, was once again a single mother. Paije, now nineteen, lived with Jacque’s sister, Debbie, in an apartment across the street from Jacque’s townhouse. Despite the differences that had led to their divorce, Jacque remained on friendly terms with Steve Sharer, who had remarried and now lived with his wife, Sharon, and her two children in nearby Jeffersonville. They saw each other at Shanda’s school activities. Shanda’s home life was as stable as could be expected for a child with divorced parents. She enjoyed her

visits to her father’s house and was pleased that she and her mother now lived so close to Paije.

“Shanda was thrilled about her and I having our own place,” Jacque said. “She used to say that we were roommates. I think it made her feel grown up.”

* * *

Hazelwood Junior High School sat behind New Albany High School in a neighborhood of older, well-kept, wood-frame houses. A military cemetery was just south of the school. From the third-floor windows of the main classroom building, students could see the hundreds of identical white gravestones, arranged in neat rows, that marked the resting places of New Albany’s war dead from the Civil War through Vietnam.

One of three public junior highs in the city of 30,000, Hazelwood drew many of its eight hundred students from blue-collar areas on the east side of town. The parents of most students worked in Louisville or in the stores and light industry of New Albany or its two sister cities, Clarksville and Jeffersonville. The three cities, nestled together on the Indiana side of the Ohio River, shared common boundaries and were so alike in size and character that visitors from Louisville often confused one with the other.