London Folk Tales (2 page)

Authors: Helen East

In a fury, he parted them, locked them all up, and forced them to marry – even those far too young. He found them hard husbands who were heavy handed and harsh-tongued. Men who kept women well under their thumb. But the new brides resisted. The worse they were treated, the stronger they grew. They met with their sisters in secret, and plotted. And one night at a signal from Alba, they acted. All poisoned their husbands – each in their own way.

By the time they were caught and condemned for this crime, it was clear that each one of them carried a child. Not wanting the blame for destroying the seed, their father had all of them put out to sea. He gave them a ship, but no sails and no oars, no rudder, no water and no food at all. No help and no hope, they still sang as they went, and the moon held them tight in her light, like a net.

They drifted without aim for days and days, until they came to the place beyond the waves, the lost land to the west, at the back of the north wind. Cold, fog-smothered cliffs cut sharp into the water. There the ship ran aground, and out stepped the thirty-three daughters.

And from those women came the future of that island, which they called Albion after their sister, and they peopled it with the children that they carried. Alba became the Queen, and she gave birth to a monstrous child, ferocious as his father. But yet she loved him, and she nursed him, and she named him Gogmagog.

Meanwhile across the seas, on southern winds, in warmer waters, a bloody battle brewed and broke. The Trojans and the Greeks turned friends to foes and wives to widows, all for the sake of honour and a single woman – Helen. All know of that story, and of the endless siege, broken by the wooden horse of Ulysses.

When the Trojans had been tricked and their city had been sacked, many died, but some survived. Amongst the ones that did, who fled across the sea to safer lands, was a man named Aeneas; and with him was his son. They took a piece of stone from the walls of Troy, so the memory of its glory should not be wholly lost.

The years passed. New roots grew. The son was married and his wife gave birth. But all the while she struggled, they could hear the Moirae muttering the destiny of the child to come:

This thread of fate winds dark and light.

For mother and father he brings death.

In lands behind the north wind’s breath

He leads a whole new nation into life.

Well the birth was hard and the boy was big, and the mother died from the labour. So that was the first warning come true.

They called the boy Brutus, and he grew swiftly. His father was always his closest companion. But when he was ten years old, the two went hunting and Brutus fired an arrow too much into the wind. It turned in the air and fell straight back, and hit his father in the heart. So that was the second threat proved, too.

Then his grandfather Aeneas decided it was time for him to go on his way; to test the truth of the third prophecy. He gave him a boat, with silver sails, and the boy chose companions to travel with him, and took the piece of stone from Troy also.

Away they went as the winds took them, with the land but a shadow on the horizon.

They sailed for days and for weeks and for years until they were weather-beaten and hardened by their travels. And many adventures they had along the way. But at last they came to a leg of land that jutted out, with nothing beyond but the sea.

There was a harbour town there where they landed, and the lord of the land came out to meet them. When Brutus told him of their quest he begged them to stay with him and rest.

‘And perhaps you will wish to stop here, where it is safe,’ he said. ‘For the land you seek, at the back of the north wind, is the place that we call Death. Beyond the grey cold sea, beyond all life that we know.’

But Brutus said no – he was following his Fate, and had to see if the words he had heard were true.

Then the lord sighed and nodded his head. ‘There are some in this town,’ he said, ‘who are strong, adventurous and young, and would wish to travel with you if you would let them come. And amongst them is my son. Like you, he is destined for more than he will find here, though I have always wanted him to stay.’

Then Brutus was happy, and they met with the young men of the town. And of those that joined them, the strongest and the tallest and the most eager of them all was Corineus, the son of the old lord. He was a giant of a man, and an adventurer after Brutus’ own heart. In no time they were friends, and Corineus became the second in command. And now they were ready to go on.

Together they travelled; teeth into the north wind and with every day it got colder and darker, and the waves rose higher and wilder. Until, at last, they came to tall white cliffs that seemed to reach from the sea to the sky. And when they landed they saw that it was a place of giants.

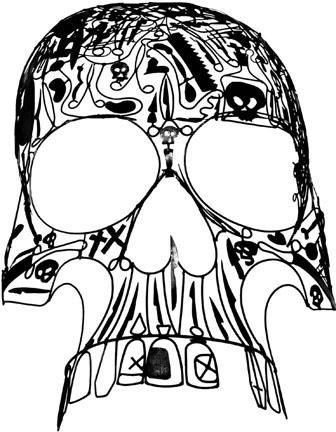

The leader of them all was Gogmagog, twelve cubits high, as hard and harsh as rock. When he saw them climbing up towards him, he laughed with all the force of a storm wind. ‘Come all at once against me,’ he cried, ‘and I will still destroy you with one blow!’

Then Corineus stepped forward and begged Brutus for a chance to prove his strength alone. And when the right was given him, he turned towards great Gogmagog and challenged him.

At once the giant caught him in his arms, and gave Corineus a hug so terrible it broke three of his ribs. But the young hero tore himself away, and then, enraged, ran head to belly, knocking him so hard that Gogmagog fell back and smashed his head against the stony ground. Yet, in a moment he was up again as if he’d merely paused to rest in bed. And so the fighting went, Gogmagog with ever-increasing strength at every fall, until, at last, Corineus, forced down onto his knees, pulled out his sword, and with both hands swung it round. He sliced the giant through, so he was cut in two. Both halves fell down upon the earth, but as they lay, the mangled limbs began to move and creep to meet their other parts, and to grow together into one again.

‘How can this be, against all nature’s laws?’ Corineus cried.

‘But it is not,’ the giant replied. ‘The Earth herself is my great grandmother. In her hold, I will grow whole. She will never see me suffer.’

Then Corineus understood that he would never win by fighting man to man as he had always done. But in that instant too, he knew what he must do. Catching Gogmagog by surprise, he snatched him up before his wounds had time to fully heal, and heaving him over his shoulder, held him up as high as he could. The giant tried to struggle, but, distanced from the ground, he was weakening fast.

Then, balancing his burden as best he could, Corineus turned and ran along a jagged splinter of land that reached far out into the sea. At its sharp tip he caught his breath, and then hurled great Gogmagog over the cliff’s edge, plunging him headlong from that great height into the angry water. Down into the foam he fell, far beyond the Earth’s soft touch, sinking deep into the ocean, subject to the Sea’s dominion. And when his body tore upon the ocean floor, the blood came bubbling forth and lay like sunset froth upon the waves, staining the sea, sand, cliffs and land.

To this day, the earth along that shore is still rich red. And the high point, where Gogmagog fell, is called ‘Langoemagog’. As for that long leg of land touching the sea to the south and the west, it became known as Cornwall, after Corineus, who settled there as governor.

But Brutus and the rest of his men went on their way, towards the setting sun. After some days they found a stream that trickled from a high-pointed hill. They followed this until it widened into a great river, and flowed at last towards the east and into the sea. But before it came to that, there was a place where it was possible to ford the river, and there was good solid ground rising up on the northern side. There they stopped to rest, and Brutus said this was the place to build a settlement.

When they had done that, he marked all around to show the extent of the place, and put up defences where it was needed, and then made an entrance way to come in by. On either side of that they made two great figures, as guardians of the gate, and they were known as Corineus and Gogmagog – in memory of the two great fighters, and the battle between them to win the land of Albion.

And finally Brutus took his talisman, the great stone brought by Aeneas from Troy, and he set it in the centre of the new settlement. Then they named it after the old city, ‘Troynovante’ or New Troy, and Brutus told them that one day it would become a great city too, and the heart of the whole island.

They say that Brutus renamed the island, and it was known from then as Britain, after him, and the race that he founded were called the Brits, or Britons. As for his settlement, it grew as he had prophesised, into a city that eclipsed even Troy in fame; only the name changed again and again until it became known as London.

Some say all of this is nothing but a tale. Yet the Stone of Brutus continues to stands here, and can be seen still within London’s city walls. And the giant guardians are remembered too, although their effigies have had to be remoulded time and again, and their looks and then their names have altered too. Corineus eventually slipped from public memory, and Gogmagog was then split into two. So the images carved in medieval times, guarding the gates of the London Guildhall, or the statues seen today standing in the hallway there, and paraded through the London streets in each Lord Mayor’s show, are now known as brother giants, Gog and Magog, the ancient defenders of the realm.

B

RAN THE

B

LESSED

As night follows day, and light and dark are two halves of the same circle, so was King Bran, the Raven, to his sister Branwen, the White One. Bran the Blessed was king of these isles, a giant of a man, and the last of the great race. Tall as an oak, he could wade halfway across the sea to Ireland in the west, without the need of a boat.

It was to that country he was looking now, and the royal ships arriving from there; for he was hoping that a match between his sister and the king of that land, Matholwch, would bring a union of affection, and a settled peace to them all.

So it seemed to prove, for when the bridal pair met together, in the palace of Harlech, there was a flame of liking lit between them, which promised to grow into love.

But Bran and Branwen had two half-brothers by another father, who were in every way the opposite of each other. Nisien was serene, a listener and peacemaker, while his brother Efnisien was resentful and rash, and the centre of endless disputes.

Because of this Bran decided not to invite Efnisien to the wedding feast. That was his first and his worst mistake – for the circle was broken and Efnisien was insulted. And so, when his chance came, he sowed the seeds of conflict. On the morning of the wedding, he went to the royal stables where the King of Ireland’s beautiful horses were steaming and stamping all ready to ride out with their new friends, the horses of the Isles of Britain.

He went to each of the horses, the finest steeds of Ireland, the guests of his brother, the king, and cut off each and every one of their tails, their ears and their lips.

When Matholwch saw how his horses had been maimed, he was beside himself with grief and rage. Bran gave him equal horses from his own stables, and ten times the value of the animals in gifts of incomparable riches and magical power, which the King of Ireland accepted as compensation for the deed, but the insult cut so deep into the hearts of the Irish, it was never to be healed.

This was the cause of the wars to come. Although the wedding went ahead, and Branwen went with her new husband home to Ireland, and within a year bore him a son and heir, the harm done to the horses festered in the mind of the Irish people. And at last they rose up, and demanded that the insult be repaid.

And so Branwen, the Queen, was stripped of all her honours. Her son was taken from her and she herself was sent down to the kitchens to be the maid of all work, the lowest of the low. And every day the cook, all greasy from his work, would box her ears until her whole head rang and she could scarcely hear. All this she endured without a word, in secret sorrow, all alone.