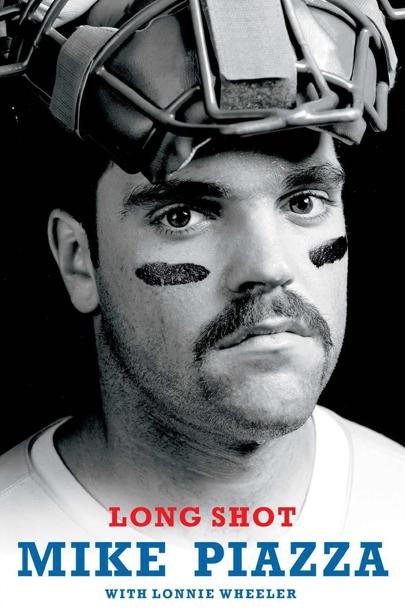

Long Shot

Authors: Mike Piazza,Lonnie Wheeler

Thank you for purchasing this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C

LICK

H

ERE

T

O

S

IGN

U

P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

This book is dedicated to my incredible family.

To my mom, who gave me a firm foundation and the gift of faith; my dad, who believed in me even more than I believed in myself; and my brothers, Vince, Danny, Tony, and Tommy, whose support was unfailing

and unconditional.

To my wife, Alicia, the most beautiful and generous person I ever met.

And to our daughters, Nicoletta and Paulina, to whom I say: words cannot describe the love I feel for you. I pray that you will find peace and love in your lives always.

God bless you.

PROLOGUE

Including Pudge Rodriguez, who was dressed for work in his Detroit Tigers uniform, the greatest living catchers were all gathered around, unmasked, on the grass of Shea Stadium. From the podium, where my stomach tumbled inside the Mets jersey that I had now worn longer than any other, the Cooperstown collection was lined up on my right. Yogi Berra. Gary Carter. Johnny Bench, the greatest of them all. And Carlton Fisk, whose home run record for catchers I had broken the month before, which was the official reason that these illustrious ballplayers—these idols of mine, these

legends

—were doing Queens on a Friday night in 2004.

I preferred, however, to think of the occasion as a celebration of catching. Frankly, that was the only way I

could

think of it without being embarrassed; without giving off an unseemly vibe that basically said, hey, thanks so much to all you guys for showing up at my party even though I just left your asses in the dust. I couldn’t stand the thought of coming across that way to those four. Especially Johnny Bench. As far as I was concerned, and still am, Johnny Bench was the perfect catcher, custom-made for the position. I, on the other hand, had become a catcher only because the scouts had seen me play first base.

Sixteen years after I’d gladly, though not so smoothly or easily, made the switch, the cycle was doubling back on itself. Having seen enough of me as a catcher, the Mets were in the process of moving me to first. It was a difficult time for me, because, for one, I could sense that it signaled the start of my slow fade from the game. What’s more, I had come to embrace the catcher’s role in a way that, at least in the minds of my persistent doubters and critics, was never returned with the same level of fervor. As a positionless prospect who scarcely interested even the team that finally drafted me, catching had been my lifeline to professional baseball—to this very evening, which I never could have imagined—and I was reluctant to let it go. To tell the truth, I was afraid of making a fool of myself.

It was a moment in my career on which a swarm of emotions had roosted, and it made me wish that Roy Campanella were alive and with us. Early on, when my path to Los Angeles was potholed with confusion, politics, and petty conflict, Campy, from his wheelchair in Vero Beach, Florida, was the one who got my head right. Back then, I hadn’t realized what he meant to me. By the time I did, I was an all-star and he was gone. I surely could have used his benevolent counsel in the months leading up to my 352nd home run as a catcher, when detractors who included even a former teammate or two charged me with overextending my stay behind the plate in order to break the record (which I ultimately left at 396).

That, I think, was the main reason I wanted to understate the special night. If it appeared in any fashion that I was making a big thing out of passing Fisk, it would, for those who saw it that way, convict me of a selfish preoccupation with a personal accomplishment. Jeff Wilpon, the Mets’ chief operating officer, had gone beyond the call of duty to put the event together, and had assured me that it would stay small. At one point, as the crowd buzzed and the dignitaries settled in and my brow beaded up, I muttered to Jeff, “So much for a small ceremony.” General Motors, the sponsor, gave me a Chevy truck. (Maybe

that’s

why my dad, a Honda and Acura dealer, was wiping away tears up in our private box.) Todd Zeile and Braden Looper had graciously mobilized my teammates, and, on their behalf, John Franco presented me with a Cartier watch and a six-liter bottle of Chateau d’Yquem, 1989, which will remain unopened until there’s a proper occasion that I can share with a hundred or so wine-loving friends. Maybe when the first of our daughters gets married.

Meanwhile, the irony of the evening—and, to me, its greatest gratification—was that, in this starry tribute to catching (as I persisted in classifying it), the center of attention was the guy who, for the longest time, only my father believed in. The guy whose minor-league managers practically refused to put behind the plate. The guy being moved to first base in his thirteenth big-league season. The guy whose defensive work the cabdriver had been bitching about on Bench’s ride to the ballpark.

But Bench understood. So did Fisk. “This is a special occasion for us catchers,” he explained to the media. “Only we as catchers can fully appreciate what it takes to go behind the plate every day and also put some offensive numbers on the board.”

Fisk had kindly called me on the night I broke his record, then issued a statement saying that he’d hoped I’d be the one to do it. That had made my week; my

year

. “I’m blessed,” I told reporters. “I’ve lived a dream.”

I also mentioned that I might write a book someday.

CHAPTER ONE

I celebrated my first National League pennant in 1977, in the clutches of Dusty Baker, who played left field for the Dodgers and had just been named MVP of the League Championship Series against the Phillies. Wearing a grin and a Dodgers cap, I was hoisted up in Dusty’s left arm, and my brother Vince was wrapped in his right. My parents have a picture of it at their house in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

It was through the graces of my father and his hometown pal, Tommy Lasorda—who was in his first full year as a big-league manager—that we were permitted inside the Dodgers’ clubhouse at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia. I had just turned nine and was well along in my fascination with baseball. The season before was the first for which we’d had season tickets to Phillies games, box seats situated a few rows off third base—a strategic location that offered a couple of key advantages. One, I had a close-up look at every move and mannerism of my favorite player, Mike Schmidt. And two, Lasorda, that first year, was coaching third for Los Angeles.

He was already something of an icon around Norristown, Pennsylvania, where he had been a star left-handed pitcher, idolized especially by Italian kids like my dad, who was quite a bit younger. But I knew almost nothing about Tommy until we settled into our seats one night, the Dodgers came to bat in the top of the first inning, and my father suddenly bellowed out, “Hey, Mungo!” (When they were kids, Tommy and his buddies took on the names of their favorite big-leaguers. Lasorda’s choice was Van Lingle Mungo, a fireballer for the Brooklyn Dodgers whom he mistakenly thought was left-handed.) Tommy shouted back, and it went on like that, between innings, for most of the night. I’m sure it wasn’t the first time I was impressed by my dad, but it was the first time that I distinctly recall.

Even more pronounced is my memory of that clubhouse celebration in 1977. In addition to Dusty Baker’s uncle-ish pickup, I remember the trash

can full of ice and the players pouring it over the head of my dad’s friend. I remember my first whiffs of champagne. I remember all these grown men in their underwear and shower shoes. (This, of course, was an old-school clubhouse, prior to the infiltration of female reporters and camera phones.) I remember being startled by the sight of Steve Yeager, the Dodgers’ catcher, naked. And the last thing I remember from that night is my dad driving us home to Phoenixville—it was before his dealerships had taken off and we moved to Valley Forge—and then heading back out to party some more with the Dodgers’ manager.

In those years, my mom would hardly see him when Lasorda was in town.

• • •

When he was sixteen, having dropped out of school by that time, my father took a job grinding welded seams at the Judson Brothers farm equipment factory in Collegeville, where

his

father was a steelworker. At the end of each week, he’d shuffle into line, just behind his old man, to collect his twenty-five dollars in cash. Then, on the spot, he’d hand over twenty-four of them to my grandfather.

That was the culture he grew up with. As a younger kid, he had a paper route and various other little jobs, and turned over most of

that

money to his father. Maybe he’d get a nickel back for some ice cream. At twenty, on the way to the train station, headed off to basic training after being drafted for the Korean War, my father, having nothing left of what he’d earned, asked my grandpa, “Hey, Dad, I don’t really know if I’m gonna come back . . . but if I do, what will I have to come home to?”

His father told him, “You were put on this earth to take care of me.”

My grandfather’s first name was Rosario, but he became known as Russell when he immigrated to the United States from the southern coast of Sicily at the age of eleven. I should probably start with him.

I associated my grandfather with Sundays. Every week, my mom would take the five of us—all boys—to St. Ann Church in Phoenixville, and afterward my dad would say, “Let’s go visit Grandma and Grandpa.” Vince, in particular, looked forward to those afternoons, and made them better for the rest of us. He had a way of bringing people, and the family, together. We nicknamed him “United Nations.”