Long Time No See (26 page)

Authors: Ed McBain

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #United States, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Hard-Boiled, #Series, #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Police Procedurals

The magistrate to whom Carella presented his application was the same one he’d asked for permission to open the Harris safety deposit box. He read the application carefully, and then signed the search warrant attached to it.

The sentry at the main gate would not let Carella through.

Carella showed him the warrant, and the sentry said he would have to check it with the provost marshal. He dialed a number and told somebody there was a detective here with a search warrant, and then he handed the phone to Carella and said, “The colonel wants to talk to you.”

Carella took the phone. “Hello,” he said.

“Yes, this is Colonel Humphries, what’s the problem?”

“No problem, sir,” Carella said. “I’ve got a court order here, and your man won’t let me through the gate.”

“What kind of court order?”

“To search the person of Major John Francis Tataglia.”

“What for?”

“A dog bite, sir.”

“Why?”

“He’s a murder suspect,” Carella said.

“Put the sentry on,” the colonel said. Carella handed the phone through the car window to the sentry. The sentry took it, said, “Yes, sir?” and then listened. “Yes, sir,” he said. “Yes, sir,” he said again, and put the receiver back on its wall hook. “Third building on your right,” he said to Carella. “It’s marked Military Police.”

“Thank you,” Carella said, and drove through the gate. He parked the car in the gravel oval in front of a redbrick building, and then went inside to where a corporal was sitting behind a desk. He asked for Colonel Humphries, and the corporal asked him who should he say was here, and Carella told him who he was, and the corporal buzzed the colonel and announced Carella, and then told him it was the door just ahead, please go right in.

Colonel Humphries was a man in his early fifties, tall and suntanned, with a firm handclasp and a voice that sounded whiskey-seared. He explained to Carella that he had just spoken to the post commander, who had authorized the body search, provided an Army legal officer and an Army physician were present when the order was executed. Carella understood this completely. The Army was protecting the rights of one of its own.

The five of them assembled in the post dispensary—a lieutenant colonel, who was the appointed legal officer; a major, who was the Army physician; Colonel Humphries, who was the senior military police officer on post; Carella, who was beginning to feel a bit intimidated by all this brass; and Major John Francis Tataglia, who read the court order and then shrugged and said, “I don’t understand.”

“It gives him the authority to search for a dog bite,” the legal officer said. “General Kihlborg’s already approved the search.”

“Would you mind stripping down?” Carella said.

“This is ridiculous,” Tataglia said, but he began disrobing. There were no wounds on either of his arms, but there was a bandage on his left leg, just above the ankle.

“What’s that?” Carella asked.

Standing in his khaki undershorts and tank-top undershirt, Tataglia said, “I cut myself.”

“Would you take off the bandage, please?” Carella said.

“I’m afraid it’ll start bleeding again,” Tataglia said.

“We’ve got a doctor here,” Carella said. “He’ll remove the bandage, if you prefer.”

“I’ll do it myself,” Tataglia said, and slowly unwound the bandage.

“That’s not a cut,” Carella said.

“It’s a cut,” Tataglia said.

“Then what are those perforations?”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Those are teeth marks.”

“Are you a doctor?” Tataglia asked.

“No, but anyone can see those are teeth marks.” He turned to the medical officer. “Major,” he said, “are those teeth marks?”

“They could be teeth marks,” the major said. “I would have to examine them more closely.”

“Would you do that, please?” Carella asked.

The major went to a stainless-steel cabinet, opened the top drawer of it, and took out a magnifying glass. “Would you get up on the table here?” he asked. Tataglia climbed onto the table. The doctor adjusted an overhead light so that it illuminated the wound on Tataglia’s leg. He peered through the magnifying glass. “Well,” he said, “the wound

could

have been caused by the action of canine teeth and cutting molars. I can’t say for sure.”

Carella turned to the legal officer. “Colonel,” he said, “I’d like to take this man into custody for further examination by the medical examiner and for questioning regarding three homicides and an attempted assault.”

“Well, we’re not sure that’s a dog bite,” the legal officer said.

“It’s

some

kind of an animal bite, that’s for sure,” Carella said.

“That doesn’t make it a

dog

bite. Your court order specifically authorizes search for a

dog

bite. Now, if this isn’t a

dog

bite—”

“Your medical officer said the wound might have been caused—”

“No, I said I couldn’t be sure,” the medical officer said.

“All right, what the hell’s going on here?” Carella asked.

“You want me to release this man from military jurisdiction,” the legal officer said, “and I’m just not—”

“Only pending the outcome of our investigation.”

“Yes, well, I’m not sure I can do that.”

“Do I have to get a district attorney out here?” Carella said. “Okay, I’ll call the city and get one out here. Where’s the phone?”

“Take it easy,” Colonel Humphries said.

“Take it easy,

shit

!” Carella said. “I’ve got a man here who maybe killed three people, and you’re telling me to take it

easy

? I’m going to arrest this man if I’ve got to get the president on the phone, now how about that? He’s commander in chief of the—”

“Just take it easy,” Humphries said again.

“What’s it going to be?” Carella said.

“Let me talk to the general,” Humphries said.

“Go ahead, talk to him.”

“I’ll be back,” Humphries said, and went into the next room.

Carella could hear the sound of a telephone being dialed. He began pacing. The Army officers looked through the window to the quadrangle beyond, avoiding his eyes. Tataglia had re-bandaged his leg and was putting on his clothes again when Humphries came back into the room.

“The general says it’s okay,” he said.

It wasn’t that easy.

The legal officer went along with Tataglia to protect his rights, as was usual in this country—and which wasn’t so bad when you got right down to it. Because supposing Tataglia

wasn’t

the man who’d killed Jimmy and Isabel Harris, not to mention Hester Mathieson, huh? Suppose he

wasn’t

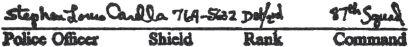

the man who’d attacked old Eugene Maslen and been bitten by his dog Ralph? Suppose he’d been bitten instead by his wife or his pussycat, huh? That was why it was necessary to have Lieutenant-Colonel Anthony Loomis there to make certain the cops of the 87th did not work Tataglia over with rubber hoses—which cops nowadays didn’t do, but which Loomis didn’t know.

When Carella asked that a sample of Tataglia’s blood be taken to compare with the blood that had been found on the sidewalk outside the Mercantile Bank on Cherry and Laird, Lieutenant-Colonel Loomis said he felt this was a violation of Tataglia’s rights. An assistant district attorney named Andrew Stewart was up at the squadroom by then because this looked like real meat and they didn’t want a multiple murderer to get away with murder even if his counsel

was

a hard-nosed career Army officer who also objected to a medical examiner taking a look at the wound to determine whether or not it was a dog bite. Stewart was a hard-nosed career man who hoped one day to become governor of the state. He had served with the United States Army during one of his nation’s many wars, and he did not like officers and he especially did not like lieutenant-colonels.

“Colonel,” he said, because that’s what lieutenant-colonels were called in the United States Army, “I think I ought to let you in on a few secrets here before you find yourself behind enemy lines without support.” He smiled like a chipmunk when he said this because he thought it was a pretty good metaphor, which in fact it was. “I am going to tell you all about Miranda-Escobedo and the rights of a prisoner. Or rather, since everybody nowadays talks about the rights of prisoners, I am going to tell you about the rights of law-enforcement officers. So pay attention, Colonel—”

“I don’t like your condescending air,” Loomis said.

“Be that as it may,” Stewart said, and smiled his chipmunk smile again. “Let me inform you that a police officer may properly ask a prisoner to submit to a blood or Breathalyzer test, to take his fingerprints or to photograph him, to examine his body, to put him in a lineup, to ask him to put on a hat or a coat, or to pick up coins, or put his finger to his nose, or anything of the sort

without

warning him first of his privilege against self-incrimination or the right to counsel.”

“That is

your

interpretation,” Loomis said.

“No, that is the interpretation of the Supreme Court of this land, Colonel. The difference between any of these actions and a statement in response to interrogation is simply the difference between non-testimonial and testimonial responses on the part of the prisoner. The first need

not

be preceded by the warnings; the second must

always

be. So, Colonel, whether you like it or not, we’re going to take a sample of Major Tataglia’s blood, and we’re also going to have an assistant ME look at that wound in an attempt to determine whether or not it was inflicted by a dog. Now that’s it, Colonel, and we’re well within our rights, and you can object till hell freezes over, but we’re

still

going to do it. Is that clear?”

“I

am

objecting,” Loomis said.

“Fine. And

I’m

calling the Medical Examiner’s Office to arrange for a man to get here right away.”

The assistant ME arrived some forty minutes later. It was now close to 9:00

P.M.

He looked at the wound and said it appeared to be a dog bite. He then asked if the dog was rabid.

“Yes,” Carella said.

The lie came to his lips suddenly and brilliantly. There was nothing in the rules that said you could not lie to an assistant medical examiner, so he instantly embroidered the lie. “The Canine Unit cut off the dog’s head and tested the brain,” he said. “The dog had rabies.”

“Then this man had better be treated right away,” the ME said, and then did an a cappella chorus on this dread disease, explaining that the incubation period might be anywhere from two to twenty-two weeks, after which the major could expect severe pains in the area of the healed wound, followed by headaches, loss of appetite, vomiting, restlessness, apprehension, difficulty swallowing, and eventual convulsion, delirium, coma—and death. He said the word “death” with a finality altogether fitting.

Tataglia remained unperturbed. He had no reason to believe that any of this was prearranged, which indeed it wasn’t. Carella wasn’t the one who’d called the Medical Examiner’s Office, nor had he said a single word to the ME before the man asked if the dog was rabid. The question seemed a natural one, the answer seemed entirely truthful, and the ME’s concern seemed only professional, that of a physician giving medical advice to a man in possible danger. But Tataglia didn’t even blink.

Carella took Stewart aside, and the men held a brief whispered consultation.

“What do you think?” Carella asked.

“I think he’s a cocky little bastard and we can break him.”

“What about the colonel?”

“Loomis doesn’t know his ass from his elbow when it comes to criminal law.”

“Do

you

want to handle the Q and A?”

“No, you take it. You know more about the case than I do.”

“Shall I show him the letter?”

“Advise him of his rights first.”

“He may decide to clam up.”

“No. When they’re this fuckin’ smart,” Stewart said, “they’re only dumb.”

Both men walked back to where the others were clustered about Genero’s desk. Genero had gone home long ago, but the blue bikini panties were still resting near his telephone.

“Major Tataglia,” Carella said, “in keeping with the Supreme Court decision in

Miranda versus Arizona

, we are not permitted to ask you any questions until you are warned of your right to counsel and your privilege against self-incrimination.”

“What is this?” Loomis asked suspiciously.

“This is known as warning your client of his rights,” Stewart said, and smiled.

“First,” Carella said, “you have the right to remain silent if you so choose. Do you understand that?”

“Yes, of course I do,” Tataglia said.

“Good. Second, you do not have to answer any questions if you don’t want to. Do you understand that?”