Long Time No See (3 page)

Authors: Ed McBain

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #United States, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Hard-Boiled, #Series, #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Police Procedurals

She was wearing a long flannel nightgown, she always wore a gown in the winter months, slept naked the minute it got to be spring; Jimmy said he liked to find her boobs without going through a yard of dry goods. She got out of bed now, her feet touching the cold wooden floor. They turned off the heat at 11:00, and by midnight it was fiercely cold in the apartment. She put on a robe and walked toward the bedroom doorway, avoiding the chair on the right, her hand outstretched; she did not need her cane in the apartment. She went through the doorway into the parlor, the sill between the rooms squeaking, past the piano Jimmy loved to play, played by ear, said he was the Art Tatum of his time, fat chance. It was funny the way she’d cried. She had stopped loving him a year ago—but her tears had been genuine enough.

She was in the kitchen now. She stopped just inside the door. Whoever was out there was still knocking. The knocking stopped the moment she spoke.

“Who is it?” she said.

“Mrs. Harris?”

“Yes?”

“Police department,” the voice said.

“Detective Carella?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Who is it, then?”

“Sergeant Romney. Would you open the door, please? We think we’ve found your husband’s murderer.”

“Just a minute,” she said, and took off the night chain.

He came into the apartment and closed the door behind him. She heard the door whispering into the jamb, and then she heard the lock being turned, the tumblers falling. Movement. Floorboards creaking. He was standing just in front of her now.

“Where is it?”

She did not understand him.

“Where did he put it?”

“Put what? Who…who are you?”

“Tell me where it is,” he said, “and you won’t get hurt.”

“I don’t know what you…I don’t…”

She was about to scream. Trembling, she backed away from him and collided with the wall behind her. She heard the sound of metal scraping against metal, sensed the sudden motion he took toward her, and then felt the tip of something pointed and sharp in the hollow of her throat.

“Don’t even breathe,” he said. “Where is it?”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Do you want me to kill you?”

“No, please, but I don’t know what—”

“Then where is it?” he said.

“Please, I—”

“Where?” he said, and slapped her suddenly and viciously, knocking the sunglasses from her face. “Where?” he said, and slapped her again. “Where?” he said. “

Where

?”

“You can’t explain to anyone about seasons,” Meyer said. “You take your average man who lives in Florida or California, he doesn’t know from seasons. He thinks the weather’s

supposed

to be the same—day in, day out.”

He did not look much like a sidewalk philosopher, though he was indeed on the sidewalk, walking briskly beside Carella, philosophizing as they approached the Harris apartment. Instead, he looked like what he was: a working cop. Tall, burly, with china-blue eyes in a face that appeared rounder than it was, perhaps because he was totally bald and had been that way since before his thirtieth birthday.

The baldness was a result of his monumental patience. He had been born the son of a Jewish tailor in a predominantly Gentile neighborhood. Old Max Meyer had a good sense of humor. He named his son Meyer. Meyer Meyer, it came out. Very comical. “Meyer Meyer, Jew on fire,” the neighborhood kids called him. Tried to prove the chant one day by tying him to a post and setting a fire at his sneakered feet. Meyer patiently prayed for rain. Meyer patiently prayed for someone to come piss on the flames. It rained at last, but not before he’d decided irrevocably that the world was full of comedians. Eventually, he learned to live with his name and the taunts, jibes, wisecracks, and tittering comments it more often than not provoked. Patience. But something had to give. His hair began falling out. By thirty his pate was as clean as a honeydew melon. And now there were other problems. Now there was a television cop with a baldpate. If one more guy in the department called him…

Patient, he thought. Patience.

The flurries had stopped by midnight. Now, at 10:00 on Friday morning, there was only a light dusting of snow on the pavements, and the sky overhead was clear and bright. Both men were hatless, both were wearing heavy overcoats. Their hands were in their pockets, the collars of their coats were raised. As Meyer spoke, his breath feathered from his mouth and was carried away over his right shoulder.

“Sarah and I were in Switzerland once,” he said, “this was late September a few years ago. People were getting ready for the winter. They were cutting down this tall grass, they were using scythes. And then they were spreading the grass to dry, so the cows would have that to eat in the winter. And they were stacking wood, and bringing the cows down from the mountains to put in the barns—it was a whole preparation scene going on there. They knew it would start snowing soon, they knew they had to be ready for winter. Seasons,” he said, and nodded. “Without seasons there’s a kind of sameness that’s unnatural. That’s what I think.”

“Well,” Carella said.

“What do you think, Steve?”

“I don’t know,” Carella said. He was thinking he was cold. He was thinking this was very goddamn cold for November. He was thinking back to the year before when the city became conditioned to expect only two different kinds of weather all winter long. You either woke up to a raging blizzard, or you woke up to clear skies with the temperature just above zero. That was the choice. He was not looking forward to the same choice this year. He was thinking he wouldn’t

mind

living in Florida or California. He was wondering if any of the cities down there in Florida could use an experienced cop. Track down a couple of redneck bank robbers, something like that. Sit in the shade of a palm tree, sip a long frosty drink. The thought made him shiver.

The Harris building seemed more welcoming in broad daylight than it had the night before. There was grime on its facade, to be sure—this wouldn’t be the city without grime—but the red brick showed through nonetheless, and the building looked somehow cozy in the bright sunlight. That was something people forgot about this city. Even Carella usually thought of it as a place tinted in various shades of black and white. Soot-covered tenements reaching into gray sky above, black asphalt streets, gray sidewalks and curbs, a monochromatic metropolis, ominous in its gloom. But the absolute opposite was true.

There was color in the buildings—red brick beside yellow, brownstone beside wood painted orange or blue, swirled marble, orange cinder block, pink stucco. There was color in the billboard posters—overlapping and blending and clashing so that a wall of them advertising attractions varying from a rock concert to a massage parlor achieved the dimension of an abstract painting. There was color in the traffic and the traffic lights—reds, yellows, and greens flashing on rain-slick pavements reflecting the metallic glow of Detroit’s fancy, every color in the spectrum massed here in these crowded streets to create a moving mosaic. There was color in the debris—this city had more garbage than any other in the United States, and more often than not it went uncollected because of yet another garbage strike. It lay in plastic bags against the walls of apartment buildings, the greens, beiges, and pale yellows of modern technology enclosing the waste product of a city of eight million—or torn open by rats to spill in putrefying hues upon the sidewalks. There was color, too—God help the subway rider—in the graffiti that was spray-can-painted onto the sides of the shining new mass transit cars. Latin curlicues advertising this or that

macho

male, redundant, but then, so was spraying your name fourteen times on as many subway cars. And lastly, there was color in the people. No simple blacks or whites here. No. There were as many different complexions as there were citizens.

Both men were silent as they climbed the steps to the entrance lobby. One of them was thinking about seasons, and the other was thinking about colors. Both were thinking about the city. They climbed the steps to the third floor and knocked on the door to apartment 3C. Carella looked at his watch, and knocked again.

“Did you tell her ten o’clock?” Meyer asked.

“Yes.” Carella knocked again. “Mrs. Harris?” he called. No answer. He knocked again, and put his ear to the door. He could hear nothing inside the apartment. He looked at Meyer.

“What do you think?” Meyer said.

“Let’s get the super,” Carella said.

They went downstairs again, found the super’s apartment where most of them were, on the ground-floor landing at the end of the stairwell hall. He was a black man named Henry Reynolds, said he’d been superintendent here for six years, knew the Harrises well. Apparently, he did not yet know that Jimmy Harris had been slain last night. He talked incessantly as they climbed the steps again to the third floor, but he did not mention what he would most certainly have considered a tragedy had he known of it, nor did he ask why the police wanted access to the apartment. Neither Meyer nor Carella considered this strange. Often, in this city, the citizens did not ask questions. They knew cops only too well, and it was usually simpler to go along and not make waves. Reynolds knocked on the door to apartment 3C, listened for a moment with his head cocked toward the door, shrugged, and then unlocked the door with a passkey.

Isabel Cartwright Harris lay on the floor near the refrigerator.

Her throat had been slit, her head was twisted at an awkward angle in a pool of her own blood. The refrigerator door was open. Crisping trays and meat trays had been pulled from it, their contents dumped onto the floor. There were open canisters and boxes strewn everywhere. Underfoot, the floor was a gummy mess of blood and flour, sugar and cornflakes, ground coffee and crumpled biscuits, lettuce leaves and broken eggs. Drawers had been overturned, forks, knives, and spoons piled haphazardly in a junk-heap jumble, paper napkins, spaghetti tongs, a corkscrew, a cheese grater, place mats, candles all thrown on the floor together with the drawers that had contained them.

“Jesus,” Reynolds said.

The body was removed by 12:00 noon. The laboratory boys were finished with the place by two, and that was when they turned it over to Meyer and Carella. The rest of the apartment was in a state of disorder as violent as what they had found in the kitchen. Cushions had been removed from the sofa and slashed open, the stuffing pulled out and thrown onto the floor. The sofa and all the upholstered chairs in the room had been overturned, their bottoms and backs slashed open. There was only one lamp in the living room, but it was resting on its side, and the shade had been removed and thrown to another corner of the room. In the bedroom, the bed had been stripped, the mattress slashed, the stuffing pulled from it. Dresser drawers had been pulled out and overturned, slips and panties, bras and sweaters, gloves and handkerchiefs, socks and undershorts, T-shirts and dress shirts scattered all over the floor. Clothing had been pulled from hangers in the closet, hurled into the room to land on the dresser and the floor. The closet itself had been thoroughly ransacked—shoe boxes opened and searched, the inner soles of shoes slashed; the contents of a tackle box spilled onto the floor; the oilcloth covering on the closet shelf ripped free of the thumbtacks holding it down. It seemed evident, if not obvious, that someone had been looking for something. Moreover, the frenzy of the search seemed to indicate he’d been certain he would find it here.

Carella and Meyer had no such definite goal in mind, no specific

thing

they were looking for. They were hoping only for the faintest clue to what had happened. Two people had been brutally murdered, possibly within hours of each other. The first murder could have been chalked off as a street killing; there were plenty of those in this fair city, and street killings did not need motivation. But the second murder made everything seem suddenly methodical rather than senseless. A man and his wife killed within the same twenty-four-hour period, in the identical manner, demanded reasonable explanation. The detectives were asking why. They were looking for anything that might tell them why.

They were hampered in that both the victims were blind. They found none of the address books they might have found in the apartment of a sighted victim, no calendar jottings, no shopping lists or notes. Whatever correspondence they found had been punched out in Braille. They collected this for translation downtown, but it told them nothing immediately. There was an old standard typewriter in the apartment; it had already been dusted for prints by the lab technicians, and neither Carella nor Meyer could see what other information might be garnered from it. They found a bank passbook for the local branch of First Federal on Yates Avenue. The Harrises had $212 in their joint account. They found a photograph album covered with dust. It had obviously not been opened in years. It contained pictures of Jimmy Harris as a boy and a young man. Most of the people in the album were black. Even the pictures of Jimmy in uniform were mostly posed with black soldiers. Toward the end of the album was an eight-by-ten glossy photograph.

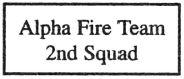

There were five men in the obviously posed picture. Two of them were white, three of them black. The picture had been taken in front of a tentlike structure with a wooden-frame lower half and a screened upper half. All of the men were smiling. One of them, crouching in the first row, had his hand on a crudely lettered sign. The sign read:

Among some documents scattered on the bedroom floor, they found the dog’s papers. He was a full-blooded Labrador retriever and his name was Stanley. He and his master had been trained at the Guiding Eye School on South Perry. The other documents on the floor were a marriage certificate—the two witnesses who’d signed it were named Angela Coombes and Richard Gerard—a certificate of honorable discharge from the United States Army and an insurance policy with American Heritage, Inc. The insured as James Harris. The primary beneficiary was Isabel Harris. In the event of her death, the contingent beneficiary was Mrs. Sophie Harris, mother of the insured. The face amount of the policy was $25,000.

That was all they found.

The phone on Carella’s desk was ringing when he and Meyer got back to the squadroom at twenty minutes past 4:00. He pushed through the gate in the slatted wooden railing and snatched the receiver from its cradle.

“87th Squad, Carella,” he said.

“This is Maloney, Canine Unit.”

“Yes, Maloney.”

“What are we supposed to do with this dog?”

“What dog?”

“This black Labrador somebody sent us.”

“Is he okay?”

“He’s fine, but what’s his purpose, can you tell me?”

“He belonged to a homicide victim,” Carella said.

“That’s very interesting,” Maloney said, “but what’s that got to do with Canine?”

“Nothing. We didn’t know what to do about him last night—”

“So you sent him here.”

“No, no. The desk sergeant called for a vet.”

“Yeah,

our

vet. So now we got ourselves a dog we don’t know what to do with.”

“Why don’t you train him?”

“You know how much it costs to train one of these dogs? Also, how do we know he has any aptitude?”

“Well,” Carella said, and sighed.

“So what do you want me to do with him?”

“I’ll get back to you on it.”

“When? He ain’t out of here by Monday morning, I’m calling the shelter.”

“What are you worried about? You haven’t got a mad dog on your hands there. He’s a seeing-eye dog, he looked perfectly healthy to me.”