Lords of Finance: 1929, the Great Depression, and the Bankers Who Broke the World

Read Lords of Finance: 1929, the Great Depression, and the Bankers Who Broke the World Online

Authors: Liaquat Ahamed

Tags: #Economic History, #Economics, #Banks & Banking, #Business & Investing, #Industries & Professions

Contents

10. A B

RIDGE

B

ETWEEN

C

HAOS AND

H

OPE

19. A L

OOSE

C

ANNON ON THE

D

ECK OF THE

W

ORLD

THIS HAS HAPPENED BEFORE.

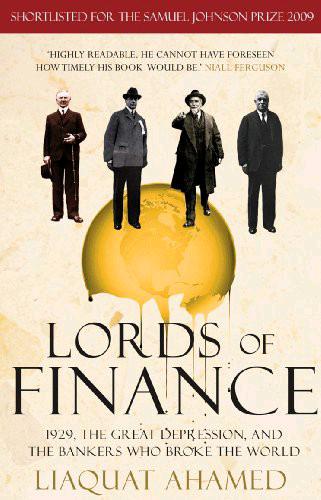

The current financial crisis has only one parallel: the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression of the 1930s, which crippled the future of an entire generation and set the stage for the horrors of the Second World War. Yet the economic meltdown could have been avoided, had it not been for the decisions taken by a small number of central bankers.

In

Lords of Finance

, we meet these men, the four bankers who truly broke the world. Their names were lost to history, their lives and actions forgotten, until now. Liaquat Ahamed’s magisterial

Lords of Finance

tells their story in vivid and gripping detail, in a timely and arresting reminder that individuals – their ambitions, limitations and human nature – lie at the very heart of global catastrophe.

Liaquat Ahamed has been a professional investment manager for twenty-five years. He has worked at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., and the New York-based partnership of Fischer Francis Trees and Watts, where he served as chief executive. He is currently an adviser to several hedge fund groups, including the Rock Creek Group and the Rohatyn Group, is a director of Aspen Insurance Co., and is on the board of trustees of the Brookings Institution. He has degrees in economics from Harvard and Cambridge universities.

Lords of Finance

, which was shortlisted for the BBC Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-fiction and which won the

Financial Times

/Goldman Sachs Business Book of the Year Award, the Spear’s Financial History Book of the Year Award, and the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for History, is Liaquat Ahamed’s first book.

Liaquat Ahamed

TO MEENA

3. U.S.

AND

UK W

HOLESALE

P

RICES

: 1910-33

4. U.S. S

TOCK

P

RICES AND

C

ORPORATE

P

ROFITS

: 1900-26

5. U.S. S

TOCK

P

RICES AND

C

ORPORATE

P

ROFITS

: 1922-36

8. I

NDUSTRIAL

P

RODUCTION

: 1925-36

Read no history

1

—nothing but biography, for that is life without theory.

—B

ENJAMIN

D

ISRAELI

Duchess of York,

August 15, 1931

INTRODUCTION

ON AUGUST

15, 1931,

THE

following press statement was issued: "The Governor of the Bank of England has been indisposed as a result of the exceptional strain to which he has been subjected in recent months. Acting on medical advice he has abandoned all work and has gone abroad for rest and change." The governor was Montagu Collet Norman, D.S.O.—having repeatedly turned down a title, he was not, as so many people assumed, Sir Montagu Norman or Lord Norman. Nevertheless, he did take great pride in that D.S.O. after his name—the Distinguished Service Order, the second highest decoration for bravery by a military officer.

Norman was generally wary of the press and was infamous for the lengths to which he would go to escape prying reporters—traveling under a false identity; skipping off trains; even once, slipping over the side of an ocean vessel by way of a rope ladder in rough seas. On this occasion, however, as he prepared to board the liner

Duchess of York

for Canada, he was unusually forthcoming. With that talent for understatement that came so naturally to his class and country, he declared to the reporters gathered at the dockside, "

I feel I want a rest

2

because I have had a very hard time lately. I have not been quite as well as I would like and I think a trip on this fine boat will do me good."

The fragility of his mental constitution had long been an open secret within financial circles. Few members of the public knew the real truth—that for the last two weeks, as the world financial crisis had reached a

crescendo and the European banking system teetered on the edge of collapse, the governor had been incapacitated by a nervous breakdown, brought on by extreme stress. The Bank press release, carried in newspapers from San Francisco to Shanghai, therefore came as a great shock to investors everywhere.

It is difficult so many years after these events to recapture the power and prestige of Montagu Norman in that period between the wars—his name carries little resonance now. But at the time, he was considered the most influential central banker in the world, according to the

New York Times,

the "

monarch of [an] invisible empire

3

." For Jean Monnet, godfather of the European Union, the Bank of England was then "

the citadel of citadels

4

" and "Montagu Norman was the man who governed the citadel. He was redoubtable."

Over the previous decade, he and the heads of the three other major central banks had been part of what the newspapers had dubbed "

the most exclusive club

5

in the world." Norman, Benjamin Strong of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, Hjalmar Schacht of the Reichsbank, and Émile Moreau of the Banque de France had formed a quartet of central bankers who had taken on the job of reconstructing the global financial machinery after the First World War.

But by the middle of 1931, Norman was the only remaining member of the original foursome. Strong had died in 1928 at the age of fifty-five, Moreau had retired in 1930, and Schacht had resigned in a dispute with his own government in 1930 and was flirting with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. And so the mantle of leadership of the financial world had fallen on the shoulders of this colorful but enigmatic Englishman with his "waggish" smile, his theatrical air of mystery, his Van Dyke beard, and his conspiratorial costume: broad-brimmed hat, flowing cape, and sparkling emerald tie pin.

For the world's most important central banker to have a nervous breakdown as the global economy sank yet deeper into the second year of an unprecedented depression was truly unfortunate. Production in almost every country had collapsed—in the two worst hit, the United States and

Germany, it had fallen 40 percent. Factories throughout the industrial world—from the car plants of Detroit to the steel mills of the Ruhr, from the silk mills of Lyons to the shipyards of Tyneside—were shuttered or working at a fraction of capacity. Faced with shrinking demand, businesses had cut prices by 25 percent in the two years since the slump had begun.

Armies of the unemployed now haunted the towns and cities of the industrial nations. In the United States, the world's largest economy, some 8 million men and women, close to 15 percent of the labor force, were out of work. Another 2.5 million men in Britain and 5 million in Germany, the second and third largest economies in the world, had joined the unemployment lines. Of the four great economic powers, only France seemed to have been somewhat protected from the ravages of the storm sweeping the world, but even it was now beginning to slide downward.

Gangs of unemployed youths and men with nothing to do loitered aimlessly at street corners, in parks, in bars and cafés. As more and more people were thrown out of work and unable to afford a decent place to live, grim jerry-built shantytowns constructed of packing cases, scrap iron, grease drums, tarpaulins, and even of motor car bodies had sprung up in cities such as New York and Chicago—there was even an encampment in Central Park. Similar makeshift colonies littered the fringes of Berlin, Hamburg, and Dresden. In the United States, millions of vagrants, escaping the blight of inner-city poverty, had taken to the road in search of some kind—any kind—of work.

Unemployment led to violence and revolt. In the United States, food riots broke out in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and across the central and southwestern states. In Britain, the miners went out on strike, followed by the cotton mill workers and the weavers. Berlin was almost in a state of civil war. During the elections of September 1930, the Nazis, playing on the fears and frustrations of the unemployed and blaming everyone else—the Allies, the Communists, and the Jews—for the misery of Germany, gained close to 6.5 million votes, increasing their seats in the Reichstag from 12 to 107 and making them the second largest parliamentary party after the Social Democrats. Meanwhile in the streets, Nazi and Communist gangs

clashed daily. There were coups in Portugal, Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Spain.