Losing Mum and Pup (23 page)

Read Losing Mum and Pup Online

Authors: Christopher Buckley

Conor led his grandfather’s coffin into the church. The pews were all filled with Buckleys. They had been well worn over the

years by my family’s knees. Lucy gave the first reading, Psalm 121, a favorite of her lovely Episcopalian family, who, charmingly,

recite it aloud together every time a family member leaves on a trip. They call it the “Going Away” prayer.

I will lift up mine eyes to the hills, whence cometh my help….

Conor did the second reading, from Ecclesiastes: “Vanity of vanity, saith the preacher, all is vanity.”

*

Father Kevin gave the homily, in which he related a conversation he’d had with Pup some years earlier, on the subject of

religious doubt. Father Kevin had said to Pup at the lunch table, “Everyone at

some

point has doubts,” and Pup had looked up from his borscht and said, “

I

never did.”

I gave the eulogy and managed to lose it halfway through the first sentence. I recovered. When I told everyone about putting

Mum in the coffin with him, saying, “It was the only way we’d get her back to Sharon,” the church exploded with laughter.

Mum had stopped coming up for Thanksgiving, well, a long time ago. At first she gave excuses, and then she stopped bothering

even with those.

It was still pouring rain, so we did the military ceremony at the entrance to the church. A citation was read. The rifleman

fired the volley. A bagpiper played “Amazing Grace.” The flag was folded into a triangle and presented to me, with the thanks

of a grateful nation. As it was handed to me, I heard sobs from behind me. The sergeant then presented Conor, standing beside

me, with the empty cartridges from the rifle volley. “Cool,” I whispered. Then a bugler sounded “Taps.” Eight of us carried

Pup out into the rain and loaded him back into the hearse. “Good-bye, my friend,” said Danny, but it wasn’t good-bye quite

yet.

21

There’s a Mr. X, Apparently

T

wo mornings later, around nine, I was in bed, groggy, still on the first cup of coffee, Pup’s dogs, Daisy and Rupert, chewing

on each other at my feet—it seemed I had inherited them along with the other stuff—when the phone rang. A voice like a sonic

boom:

“Is this Christopher Buckley?”

I stammered yes, though I was sure my affirmation could only come as a letdown to someone with such an august voice.

“This is Car-dinal Egan.”

I sat bolt upright. (Once an altar boy, always an altar boy.) “Yes,” I said, trying frantically to remember the correct ecclesiastical

title, “Your”—

Grace? Excellency?

…

quickly, man!—aha—

“Eminence.”

Pup and I had discussed funeral arrangements some years ago. He’d said, “If I’m still famous, do it at Saint Patrick’s.

*

If not, just do it in Stamford at Saint Mary’s.” To judge from the amount of ink and TV coverage his death was generating,

he was very much “still famous.” I’d sent word through a priest friend up the chain of command to the archdiocese, asking

if the cathedral might be available. Now the cardinal was calling. I was impressed by the fact that he’d dialed the number

himself. None of that “I have His Eminence. Please hold, you miserable, sinful wretch.” He was jovial and we joked about our

common priest friend, whom he called (in jest) “a

thoroughly

disreputable character.”

The pope was coming to town, and Easter loomed, but the cardinal found a spot on the cathedral calendar between this rock

and that hard place. Mother Church can be a bureaucracy, to be sure, but when she moves, she moves with sureness.

†

My first call was to Henry Kissinger. “Well, Henry,” I said, “I seem to do little else these days but ask you to give eulogies.”

He choked up and said that it would be an honor. I mean this as a compliment: For a Teuton with a steel-trap mind who was

once more or less in charge of the world, Henry Kissinger has a heart of Jell-O. He is a certifiable member of the Bawl Brigade.

He said he wasn’t sure he’d be able to get through it. I said I’d sit in the front pew and make faces at him, if he’d do the

same for me while I gave mine.

Word went out, and once again I was impressed with the celerity of our Internet age. Calls started coming in right away. I

had decided to make the funeral open to the public, partly for good, partly for selfish reasons. I’d spent a great many man-hours

on Mum’s (of necessity) invitation-only memorial service, and it’s no fun at all having to tell so-and-so that, no, sorry,

Aunt Irma and Cousin Ida can’t come, even if they were great admirers. I didn’t want to play rope-line bouncer at St. Pat’s.

You—okay. No, you can’t come in. Oh, yes, Mr. Vidal, we’ve been expecting you. We have you right up front, next to Norman

Podhoretz.

The White House called. The president could not attend but would like Vice President Cheney to attend; moreover, he would

like Vice President Cheney to speak. This was very thoughtful of the White House, but problematic. I envisioned two thousand

people standing in line waiting to file through Secret Service metal detectors—and in the rain, almost certainly, since it

had so far poured on every event connected with Pup’s departure from this vale of tears. I said to the White House,

That’s very thoughtful, and I am sincerely touched, but given the security requirements, perhaps it would be best to pass.

The White House called back and said,

We’re not trying to “sell” you, but we do this all the time. The vice president attended Mike Deaver’s and Jeane Kirkpatrick’s

services, and the disruption was minimal.

I thought,

How I wish I could discuss this with Pup!

Pup just loved dilemmas of this kind. He would not have been blasé about being paid tribute to by a sitting vice president

of the United States. But having myself been through many a Secret Service metal detector, I know very well that the disruption

is not exactly “minimal,” and the prospect of two thousand well-wishers having to empty their purses and being spread-eagled

and wanded at the church door was not a consummation devoutly to be wished.

There was this, too: If Mr. Cheney came, he must be allowed to give remarks. But His Eminence had made it clear—gently—that

there would be a limit of two eulogies. Over the years, there’s been an inflationary tendency to pile on the eulogies, and

Mother Church has started to put down her foot, on the perfectly reasonable principle that a funeral or memorial mass is a

sacrament, not a meeting of the Friars Club. (

Let’s save the roasting for the afterlife, shall we?

) The archbishop of Newark, New Jersey, had recently issued a ukase to the effect that there would be

no

eulogies at all in his archdiocese. (A bit harsh, methinks, but there it is.) At any rate, this left me with a Hobson’s choice:

Tell Henry Kissinger to step aside or give up my own slot. So there was nothing to do but decline the White House, as gently

as I could.

There was a lively presidential campaign going on at the time (you may have heard about it). Pup being who he was, I wondered

if we would be hearing from the presumptive Republican nominee, Senator John McCain. We never did, not a peep; odd, I thought,

as he and I are old acquaintances. But presidential campaigns are, God knows, busy times.

*

Also odd, but very sweetly so, were the calls that did come in. One of the first was from Senator John Kerry. There was zero

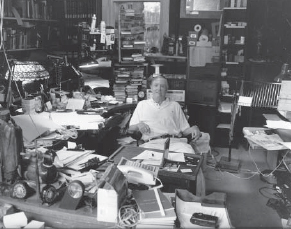

reason for him to have done that; it was a grace note, pure and simple. And then, one day as I was sitting in Pup’s study

feeling sorry for myself as I set about the (truly) enormous task of clearing it out, the phone rang. A gentle, sandpapery

voice came on the line: “I’m looking for Christopher Buckley.”

Yes, this is he.

“Oh, Chris, it’s George McGovern calling.”

Pup and George McGovern were political antipodes, but they had become good friends a decade earlier after engaging in a series

of public debates. I remembered Pup grinning one day over lunch, announcing, “Say, have I told you about my new best friend?”

(Pause. Twinkle of the eyes.) “

George McGovern!

He turns out to be the single nicest human being I’ve ever met.”

I recall my jaw dropping. When he ran for president in 1972, Pup had written and spoken some pretty tough things about George

McGovern. As I winched my lower mandible back into place, I reflected that it wasn’t all that improbable. Some of WFB’s great

friendships were with card-carrying members of the vast left-wing conspiracy: John Kenneth Galbraith, Murray Kempton, Daniel

Patrick Moynihan, Ira Glasser (head of the ACLU, for heaven’s sake), Allard K. Lowenstein, and so on. But there were piquant

ironies to the friendship with McGovern.

As I’ve previously noted, Pup’s boss at the CIA in 1951 was E. Howard Hunt. Howard was, as you know, arrested in June 1972

whilst jimmying open the door to the Democratic National Headquarters at the Watergate, in an effort, among other things,

to put paid to George McGovern’s presidential campaign. (A Pyrrhic bit of burglarizing, given what happened the following

November, when only one state went for McGovern.) Pup had left the CIA’s employ in 1952, but had remained friends with Hunt

and was godfather to—and, indeed, trustee on behalf of—several of his four children.

As Watergate unfolded, I found myself, home on some weekends from college, in the basement sauna with Pup after dinner, listening

as he confided his latest hush-hush phone call from Howard. This was dramatic stuff. The calls would come at prearranged times,

from phone booths. One night, Pup looked truly world-weary. Howard’s wife, Dorothy, had just been killed in a commercial airline

crash while on a mission delivering hush fund money.

It turns out that there’s a safety deposit box…

I was twenty-one, an aspirant staff reporter on the

Yale Daily News

. Watergate was a huge story. No, make that the biggest story since the sack of Rome.

Oh

, how my little mouth salivated. Not that I could repeat a single word of any of this.

A safety deposit box?

There’s a Mr. X, apparently. The way it works is this: I don’t know his identity, but he knows mine. Howard has given him

instructions: If he’s killed—

Killed? Jesus….

If

something

happens—whatever—in that event, Mr. X will contact me. He has the key to the safety deposit box. He and I are to open it together.

And?

Pup looked at me heavily.

Decide what to do with the contents.

Jesus, Pup.

Don’t swear, Big Shot.

What… sort of contents are we talking about?

This next moment, I remember very vividly. Pup was staring at the floor of the sauna, hunched over. His shoulders heaved.

He let out a sigh.

I don’t know, exactly, but it could theoretically involve information that could lead to the impeachment of the president

of the United States.

This conversation was taking place in December 1972. In the post-Clinton era, the word

impeachment

has lost much of its shock value, but back then, before the revelation of the Oval Office tapes or the defection of John

Dean, the phrase

impeachment of the president of the United States

packed a very significant wallop. I was speechless. Pup was, to be sure, a journalist, but he took no pleasure in possessing

this odious stick of dynamite. His countenance was pure Gethsemane:

Let this cup pass from me.

He would later recuse himself publicly, in the pages of his own magazine, from comment on Watergate, pleading conflict of

interest based on his status as trustee of the Hunt children.

And now George McGovern, whose campaign had been the target of Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy and the “plumbers,” was on the

phone from South Dakota, to condole someone he had never met and to say that he was planning to come to the memorial service,

adding with what sounded like a grin, “If I can make my way through this fifteen-foot-high snowdrift outside my house.” I

put down the phone and wept.