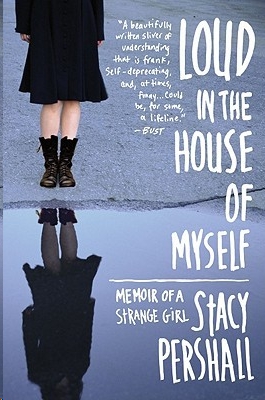

Loud in the House of Myself

Read Loud in the House of Myself Online

Authors: Stacy Pershall

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Psychology, #Personality

MEMOIR OF A STRANGE GIRL

W. W. Norton & Company

New York · London

Copyright © 2011 by Stacy Pershall

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 2012

Throughout this memoir, I have changed names and circumstances of all characters other than my immediate family in order to try to protect the privacy of those with whom I have interacted.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pershall, Stacy.

Loud in the house of myself: memoir of a strange girl / Stacy Pershall.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-393-06692-0 (hardcover)

1. Pershall, Stacy Mental health. 2. Mentally ill—Biography. I. Title.

RC464.P47A3 2011

362.196'890092—dc22

[B]

2010034823

E-ISBN: 978-0-393-08051-3

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For Glenn Becker

While working at a shop in Brooklyn, my tattoo artist Denise had an apprentice named Tasha. One day we were all hanging out in the shop looking at a book of tattoo designs by the legendary artist Sailor Jerry. The drawings were crude but beautiful, and we laughed at three little pieces that had obviously been some sailors’ nicknames years ago. The first one was an eight ball, and beneath it, in plain block letters, it said, “8-ball.” The next was a beer keg, and underneath it said, “Guzzler.” But the best by far was the third, a crossed fork and knife, with the words “Chow Hound.” It didn’t take long before Tasha and I decided that, once she had Denise’s approval, she’d tattoo “Chow Hound” on my butt. And indeed, one night several months later, Tasha got out her machine and half an hour later I had Chow Hound on my ass. While lying there with the two of them cackling over my flesh, I thought, what in God’s name am I doing? Here I am, a former anorexic, getting a tattoo proclaiming that not only do I like to eat, I like to eat a lot.

I am trying on identities again.

It’s 1978, and I’m with my mother in the Kmart in Fayetteville, Arkansas, which, at age seven, seems like the big city to me. I sit at a dressing table, wearing a Farrah Fawcett-style wig (because in those days, Kmart sold wigs) and a large floppy beige hat that is supposed to look like straw but is actually made of cheap nylon. Perched precariously on my nose is a pair of pink-tinted sunglasses several sizes too big. I am eating puffy peppermint meringue candies, for which my mother has not yet paid, and writing in a small blue notebook with yellow pages and a cutesy drawing of a flapper on the cover, for which she also has not yet paid. This is important work. I am taking notes.

Two women pass me and giggle. I glance at their reflections in the dressing table mirror and proceed to record every detail of their appearance and conversation, congratulating myself on how inconspicuous I am. I am Harriet the Spy, and I am training myself to be as surreptitious as possible.

Kmart doesn’t have everything my mother wants, so we make a stop at Wal-Mart, which, besides the various Baptist churches in the area, is the hub of northwest Arkansas social life. My mother stops to chat with someone she knows and I am free. Wigless now, myself again, I run for my next disguise.

The crafts section is in the far right corner of the store, a distant wonderland of rickrack, fake flowers, and cheap fabric. In Wal-Mart, I am a dancer. I have the power to defy gravity. I fold myself into the bolts of multicolored mesh, trying to wrap myself so that it completely obscures my vision. I want to see nothing but my future, nothing but the costume I will wear when I am a decade older and famous and thousands of miles away from my thousand-person hometown of Prairie Grove, twenty miles south of Fayetteville. With age will come grace and sophistication. I will be magically teleported to New York City on waves of talent. I will be carried on a magic carpet of tulle. This is what I live for. It is what I have to believe to survive.

I learned about New York City from an episode of

The Love Boat

featuring Andy Warhol. He prowled around the ship with a Polaroid camera, a silver wig, and a pair of big red plastic glasses. From that point on, I relentlessly compared Prairie Grove to New York and knew it was where I belonged.

Prairie Grove is one of those small towns that seem removed from time. Fayetteville is, like the rest of America, being subsumed by subdivisions and strip malls, but Prairie Grove has hardly changed at all. There is still no McDonald’s, no Starbucks. There are still only two traffic lights. They still hang the same battered light-up Santas and snowmen they’ve used for at least thirty years on the light poles of Main Street at Christmas.

You can still stroll past Lou Anna Bellman’s flower shop, and if the door is open you’ll smell carnations. You can fill prescriptions at Rexall Drug, where the same cracked orange plastic sign still announces the place, and the same three bottles of Lemon-Up shampoo sit on a half-empty shelf, a layer of dust cascading like snow down their plastic lemon caps. There are still cowboy boots and stiff indigo Wrangler’s to be bought at Crescent’s, where the dressing room still has pine paneling.

At the other end of the street is the Farmers & Merchants Bank and the Beehive Diner, where the air is saturated with countless years of cigarette smoke, cooking grease, and stale coffee, and the same faded photos of chimps in human clothing, dumping plates of spaghetti over their heads, still hang on the wall. The old Laundromat is still there, but the front of it is now a beauty shop.

Once you’ve ridden your bike through the ditch outside the Dersams’ house enough times, and made multiple barefoot treks to the One-Stop Mart to get the same slightly overfrozen Rocky Road ice cream cones, and worn a path through the overgrown field that is a shortcut between Marna Lynn Street and home, you’ve basically seen it all. If you’re a strange and sensitive kid, you’re ready to blow the joint by the time you’re seven.

And I was that kid, the weird kid, the strange girl, the crazy one. In a town of a thousand people, reputations are hard to live down. There was a forced intimacy there I am deeply grateful not to have today, in New York City, where even though I’m a tattooed lady with flaming red dreadlocks, I can exist in relative anonymity on a day-to-day basis. In Prairie Grove, people thought nothing of going to the gas station barefoot or with perm rods in their hair; they knew their neighbors well enough they might as well have been in their own living room. When you went to town, you saw the same characters, like the old lady who rode around with her poodle in the basket of her bike, or Mary Frances the square-dance teacher, or the unsmiling Hendersons, with their five kids lined up in the driveway half an hour before all the garage sales opened. And, most spectacularly and terrifyingly, there was Susannah, the March of Dimes poster child.

Susannah was the younger sister of Sheridan, one of the most popular girls in school, and she had a disease called Apert syndrome, which meant her face was all messed up, the middle part sunken in and her eyes bulging. They hung her posters in the window of Dillon’s grocery store, and although they terrified me, I had an intense urge to steal one. I wanted to do with it what Ramona Quimby did with her Halloween mask, hiding it under the couch cushions so she could sneak peeks at it and scare herself when she chose. I wanted to have Susannah’s picture all to myself, knowing that just beneath my butt on the sofa was her crumpled weird eye. I wanted to stare at her face until I could almost see her reaching out to nub my own with her fused-together fingers, their one large nail growing straight across, then safely turn away at the last possible second. Most of all, I wanted to use her image as a tool, a barometer, that would help me test how off things were inside my head. I would know by how long it took before her picture started to look like it was going to come to life—I often thought photographs or inanimate objects might just do so. As a child, my grasp on reality was tenuous, and it only became more so as I got older. (I spent a lot of time staring at my stuffed animals and looking away just before they turned into demons, as I felt certain they would if I stared too long. I felt compelled to do this most nights before falling asleep, perhaps as a way of assuring myself I had some degree of control over my terror.)

When I saw Susannah’s mother pushing her around town in her tiny wheelchair, goose bumps swam to the surface of my skin. Anytime I left the house, I took the chance of seeing her, which meant I sometimes wanted to leave the house and sometimes didn’t. It depended on how out-of-control my thoughts already were that day.

Make me crippled,

I prayed at night,

make me like Susannah: make it able to be seen

.

Give me bright shiny crutches with gray plastic cuffs and free me from living in this brain. Make me pretty or hideous but nothing in between. Pose me on matted beige carpet, save me on film, hang me in the window so my birth defects can be seen. Make it bad enough that parents will tell their kids teasing me isn’t funny.

THIS IS THE

story of how a strange girl from Prairie Grove discovered she had a multitude of disorders and how she survived. The names of my disorders came later, and start with

b

: borderline, bipolar, bulimic. The only

a

was anorexia. These disorders have a chicken-and-egg quality. Was I bulimic because I was borderline, anorexic before bulimic, is the bipolar even real? Some physicians and researchers suggest that borderline personality disorder should be reclassified as a mood, rather than personality, disorder, and that in fact it may live on the bipolar spectrum. The symptoms overlap. If your mood swings last a week, you’re bipolar; if they last a few hours, you’re borderline. This is of course a drastic oversimplification, and when you’re in the midst of colossal emotional overwhelm, you don’t care what your disorder is called, you just want it to stop—or, in the case of early mania, go on forever.

It’s only slightly better as an adult. You give your feelings melodramatic names, grandiose status, because melodramatic and grandiose are how you’re feeling. You’re the most depressed person EVER, or, on the rare good days, the happiest—no, not happy, ECSTATIC. There is no gray, there is only the blackest black and shimmering white. The white, for which you live, is like being illuminated by a god in whom you have long since stopped believing. The black is what you more often get.

If you are this child, or this hypersensitive, emotionally skinless adult who might as well be a child, there will be therapists, long lines of them, each offering drugs and, if you have no health insurance, as much counseling as they can offer before their internships expire. Then it’s on to the next one, who may or may not have a different diagnosis and/or different drugs. The drugs usually make you gain weight and sleep a lot—or not at all—but if you’re lucky they lift the blackness for a while. If you’re bipolar, you tend to only show up in therapists’ offices when depressed, which means you will likely be diagnosed with unipolar depression and fed a steady stream of antidepressants, which will send you into glorious hypomania for a while before bottoming out and leaving you desolate again. It will generally take quite some time before someone works with you long enough to see that you have more than just depression, that there is a cycle to your moods.

I was diagnosed in this order: bulimia, major depression, attention deficit disorder (briefly, in 1993, when it first became trendy; it was later discounted), bipolar disorder, anorexia, borderline personality disorder. The first and last diagnoses were most accurate. In the spring of 2005, I entered a three-day-a-week Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) program for borderlines at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. The skills learned in the four modules of DBT—Mindfulness, Distress Tolerance, Emotion Regulation, and Interpersonal Effectiveness—are things most people learn as children. Borderlines, however, due to having been raised in what DBT creator Marsha Linehan calls an “invalidating environment,” need help figuring out how not to drown in the undertow of our own feelings.

It is embarrassing to admit I didn’t begin to acquire these skills until the age of thirty-four, when after a breakdown I began to get my life together through medication, therapy, and tatooing.

Borderline

means you’re one of those girls who walk around wearing long sleeves in the summer because you’ve carved up your forearms over your boyfriend. You make pathetic suicidal gestures and write bad poetry about them, listen to Ani DiFranco albums on endless repeat, end up in the emergency room for overdoses, scare off boyfriends by insisting they tell you they love you five hundred times a day and hacking into their email to make sure they’re not lying, have a police record for shoplifting, and your tooth enamel is eroded from purging. You’ve had five addresses and eight jobs in three years, your friends are avoiding your phone calls, you’re questioning your sexuality, and the credit card companies are after you. It took a lot of years to admit that I was exactly that girl, and that the diagnostic criteria for the disorder were essentially an outline of my life:

[

Borderline Personality Disorder is characterized by

]

a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affect, and marked impulsivity beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

1. Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Note: Do not include suicidal or self-mutilating behavior covered in criterion 5.

2. A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation

3. Identity disturbance: markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of self

4. Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging (e.g., spending, sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, binge eating). Note: Do not include suicidal or self-mutilating behavior covered in criterion 5.

5. Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats, or self-mutilating behavior

6. Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood (e.g., intense episodic dysphoria, irritability, or anxiety usually lasting a few hours and only rarely more than a few days)

7. Chronic feelings of emptiness

8. Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger (e.g., frequent displays of temper, constant anger, recurrent physical fights)

9. Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms

The first time I read these criteria, I felt like someone had been following me around taking notes. DBT and tattoos taught me how to accept and survive pain, a lesson I needed to learn physically as well as emotionally. Tattooing, like therapy, has allowed me to control the occasions on and degree to which I experience discomfort. I would not go back to my life before age thirty-five for anything in the world, but life after is shaping up to be pretty good.