Louis S. Warren (75 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

The cooperation of the Wild West camp suggested that the most primitive and potentially violent of peoples could be brought to the benefits of public health through the governance of white men like Cody and Salsbury.

79

Most of all, the complacent acceptance of the needle among the show's Germans, Indians, and other “savage” or “half-civilized” peoples implied messages for the white-collar enterpreneurs and managers who were the show's primary audience. Brooklyn's troublesome immigrants might yet be brought into the new medical and scientific order which the city's English-speaking professional bureaucracy were applying to the cities. For the reading public, the multiracial and potentially violent city teeming at the show gates could also be tamed by the proper application of authority, managerial skill, and frontier spirit.

The popular interest in public health was accompanied by professional interest in the show's infrastructure. In the historical narrative of the show's arena, old technologies like the Deadwood Stage rumbled their last before crowds anticipating new technologies. But that story came to the public through application of those new technologies, and fascination with them made Cody's camp seem both an exhibit of the primitive and a cutting-edge outfit, particularly in its use of the revolutionary technology of electricity.

Buffalo soldiers, vaqueros, Indians, and the rest of the cast in

1896.

The diningtent was the center of the show community and a frequent subject of commentary, as a place where the heterogeneous community of the Wild West

show was welded into social order. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Edison, Westinghouse, and others began to light up the cities during the early years of Cody's show. Urban dwellers had once feared nighttime in the city as frightening, dangerous, and potentially lewd. Then, in 1886, the Statue of Liberty lit up with electric light (as did the stage lighting in Cody's

Drama of Civilization,

at Madison Square Garden), and in 1893 the electrical lighting and electrical amusement rides of Chicago's White City startled and impressed millions of visitors, and thousands of columnists.

80

Electrification of the city engendered a new order of night life and public entertainments. Not only did lights make the city safer, but they created a new landscape of visual wonder, brilliant electric advertisements and white illumination which simultaneously brought new attractions into being and seemingly cleansed the city of grit and dirt which so alarmed reformers during daylight hours. In important ways, urbanites knew the working hours were over, and the time for entertainment and leisure had arrived, when the city's new electric lamps blinked on, creating the nighttime, illuminated world of “the Great White Way.”

81

In Brooklyn, electric lighting had begun to alter the city's nightscape by the early 1880s, and shortly before the Wild West show came to Ambrose Park, in the early 1890s, electric trolleys began to run on Brooklyn's busy streets.

82

The trolley was the vehicle of the modern era (the name “trolley” came from the device that conveyed the electric current from wires overhead to the car), and it soon became a ubiquitous feature of the urban landscape in Brooklyn as elsewhere. New York City had 776 miles of trolley track by 1890, and even St. Louis had 169. By 1902, Americans took 4.8 billion rides on the trolley.

83

The transformation was not easy. Because trolleys were both faster and quieter than stage coaches, wagons, and the old horse cars, pedestrians often misjudged them and paid with their lives. In 1893â94, seventeen people were killed by Brooklyn's Atlantic Avenue Rapid Transit Railroad alone, and public anxieties about the new technology ran high. Ultimately, it gave rise to the nickname “trolley dodgers” for Brooklynites (later inscribed into the city's public amusements when it was applied to their baseball team, the Brooklyn Dodgers). Nonetheless, electrification continued, and Brooklynites could take the Third and Fifth Avenue trolley lines to the Wild West show's front gates.

84

In fact, a not insubstantial crowd of observers made this trip to see the show's electrical works. The Wild West show, exhibition of vanishing skills and organic technique, was literally, and paradoxically, a beacon for electrical engineers. More than two hundred members of the New York Electrical Society accepted invitations to tour the camp's electrical works and watch the show under its new floodlights, installed and maintained by the Edison Electrical Illuminating Company. Popular newspapers and journals of electrical associations alike recounted these visits and explored the electrical circuitry of the showâ“The grounds are lighted by seventy seven 2,000-c.p. [candle power] incandescent arcs, while the buildings and tents require over 800 16-c.p. incandescent lamps.”

85

As newspaper writers were fond of reporting, the “Texas,” the electrical generating plant at Ambrose Park, was “said to be the largest for the purpose in the world.” Given the size of the area to be illuminated (the arena comprised two acres), the challenge of providing illumination had been especially great, and the generators reportedly cost $30,000.

86

The skillful attentions to the show's electrical apparatus were the culmination of efforts made by Cody and Salsbury at least since the 1880s. Circuses attempted the use of electrical generators as early as 1879, but they soon abandoned them because they were too difficult to transport. In his earliest letters to Doc Carver, Cody had broached the subject of electrical lighting for the show as a way of making more money, and their performance at Coney Island in 1883 included “Grand Pyrotechnic and Electric Illuminations.”

87

The show incorporated electric lights at long stands in Europe, in London and in Glasgow, but the 1894 season marked the beginning of the show's almost consistent electrification. By 1896, Cody and Salsbury acquired electric generators to travel with the show, and the Wild West “Electrical Department” employed eleven people. In cast parades through the streets, the mobile, gleaming, steam-powered electrical generating plants, called the “Buffalo Bill” and the “Nate Salsbury,” rolled along between contingents of frontiersmen. “The enormous double electric dynamos used to illuminate the Wild West performances are well worth inspecting, as a scientific and mechanical triumph,” trumpeted the 1898 show program. “They are the largest portable ones ever made.”

88

Even on the road, managers arranged tours of the electrical equipment, followed by performances, for visiting groups of electrical engineers and utility company officers.

89

Nighttime illumination meant the possibility of two shows a day, one in the afternoon and one in the evening, doubling gate receipts without increasing salary outlays. But it had a larger cultural meaning, too. When the show acquired the sanction of leading “scientists” (as electrical engineers were called at the time), it enhanced its mythic relevance for its audiences as both spectacle of the past and harbinger of the future, a complete reenactment of civilization's rise from nature to technology, the maturation of her people from buffalo hunters to electrical engineers.

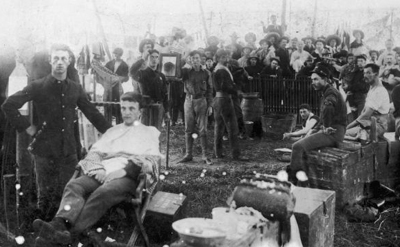

Barbershop, Buffalo Bill's Wild West, c.

1890.

A widely diverse, orderly

company town, the Wild West camp came to represent America itself. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

The electrification of the Wild West show thus implied a symbolic parallel between show and nation, each of which originated on the frontier and advanced to modernity. The machinery that made the show possible was itself a popular wonder, calling forth a collective emotional and unifying response from observers that approached what the historian David Nye and others call the “technological sublime.”

90

In some ways, the Wild West show's stature was similar to that of the railroad circus. During the 1890s, railroad circuses both imitated and symbolized modern business. They were corporate, technological, hierarchical organizations in which white male owners and operators managed the diverse and the freakish and waged near-constant advertising “wars” in which they plastered entire regions with their posters and handbills, consolidating smaller entertainments beneath ever larger tents and undercutting one another in relentless pursuit of profits. William Cody's show business career, with its beginnings in a small independent theater company and its culmination in a huge, corporate entertainment, paralleled those of the Ringling brothers, P. T. Barnum, James A. Bailey, W. T. McCaddon, and other circus impresarios who bought, sold, and consolidated traveling road shows in efforts to monopolize the industry. The circus and Wild West show business paralleled still larger developments in the American economy, where smaller concerns and entrepreneursâshopkeepers and artisansâwere shunted aside by the behemoth corporations of Vanderbilt, Morgan, and McCormick in the process that historian Alan Trachtenberg calls “the incorporation of America.”

91

Like these monopoly capitalists, Cody was, in the eyes of newspaper correspondents, a captain of industry, a modern business colossus. Nate Salsbury, the managing partner, was responsible for the tedious but essential tasks of routing the show through North America and Europe and tending to its external business matters, such as provisioning and transport. But correspondents preferred Buffalo Bill's pose as owner, director, and manager of the Wild West show, “the guiding hand of the entire enterprise,” whose “orders were obeyed” with alacrity. His creative vision and control wrought “realism, naturalism, and precision of detail” from a “heterogenous mass of human beings, representing nearly all the nations on the earth.”

92

As the 1890s progressed, Cody's publicists made ever more of his supposed managerial acumen as a “Great Manager,” “the organizer of the great exhibition which bears his name.”

93

Other circus owners received similar approbation, and thereby benefited from the era's fascination with corporate directors, but Cody had a special place. He was a frontiersman, a rustic who through his own efforts rose from common men and frontier nature to command what was at once a nostalgic show of the past and a large, modern business with a sharp technological edge. Electricity at the Wild West show underscored this managerial prowess. Unlike the few surviving scouts and old-time westerners, he was not just an aging frontiersman. He was the boss of his own industrial concern. His employees were at least as alien, recalcitrant, and potentially violent as the slew of immigrants who worked for the industrial barons of the age. And in some ways he was better at managing his crew than they were. In a nation roiled by strikesâthe Pullman strike occurred that very summerâ Wild West show employees continued to perform. Strikers in Chicago faced off against the U.S. Army. At a camp party to celebrate the elevation of Cody and Salsbury to thirty-second-degree masons in Brooklyn, John Burke joked about a strike at the Wild West show. Salsbury, with the Pullman Strikers in mind, took the opportunity to warn the show's workers against any similar “disloyalty” to the nation's armed forces. “He makes the best citizen,” he told the assembled cast, “who is most loyal to his Government. So long as you claim a Government as yours, obey its laws implicity; be loyal to that Government.”

94

The fact that Cody had no formal training as a manager, that his attributes were natural genius that came to him through experience with the show, made him all the more alluring for the new generation of white-collar managers who had little in the way of formal business training themselves, whose multiracial subordinates must have seemed at least as unruly, and potentially as violent and dangerous, as Cody's, and whose jobs were so cerebral and new that many wondered if managing was real work at all. In implying and embodying the modern corporation, Buffalo Bill's Wild West lent the corporationâthis most modern and undemocratic of business organizationsâboth a profoundly American, frontier past and a glorious future as the culmination of progress.

95