Louis S. Warren (91 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

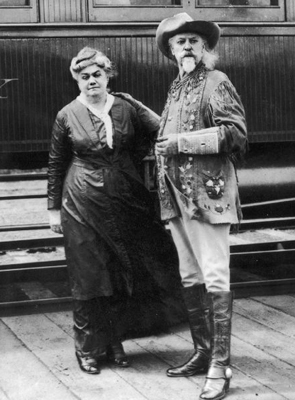

William F. and Louisa Cody, c.

1915.

They traveled together in his

later show days. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

The tedious plot was one factor which undermined the film's appeal. Another was that film was a less than ideal medium for Buffalo Bill Cody. The dispute between Cody and Miles over how best to achieve authentic scenes reminds us of Cody's arena successes and suggests why film worked poorly as a vehicle for his own myth. He had pioneered an art form in which he danced across the line between fake and real, emerging from painted backdrops and then disappearing back into them, surrounding himself with frontier relics and fakery, real frontier people and actors dressed up like them, and begging audiences to separate the two.

Early filmmakers often constructed narratives about real historical figures. Marshall Bill Tilghman, of Oklahoma, made films about his exploits starring himself. To enhance the middle-class appeal of his movies, he toured with them and lectured boys in the audience to stay away from crime. Likewise, Cody toured with

The Indian Wars

for three weeks in 1916, once appearing onstage with Sioux warriors.

62

But Cody was so aged by this time that he appeared less the frontier hero and more the grizzled Plains veteran. He was still interesting. But film was not as effective a form for testing the borders of truth and fiction, simply because it did not allow him to step out of the projection the way that arena performance did. Film worked best when it deployed scenery, lighting, props, and physical types to cue audiences, not necessarily when it showed “real” people on a flat screen.

Unfortunately the film remains a mystery, because the nitrate stock on which it was recorded disintegrated over time. Only a few fragments of it are known to exist.

As he waited for the film to debut, Cody endured more trouble with Tammen. After Cody had toured with the Sells-Floto Circus for two years, Tammen told him his debt was paid, then reneged and told him he still owed $20,000 and that he would have to pay it back with his salary. Cody wrote an old friend, “This man is driving me crazy. I can easily kill him but as I avoided killing in the bad days I don't want to kill him. But if there is no justice left I will.”

63

When Tammen arrived in Lawrence, Kansas, to meet with Cody, he was afraid to go into the old scout's tent. When he finally did, they had a tense conversation, the upshot of which was that Cody agreed to finish the 1915 season with Sells-Floto. Tammen refused to cancel the loan, but he agreed to stop taking payments out of Cody's salary. At the end of the season, Cody was without employment for the first time since entering show business.

64

Not to be deterred, he scrambled to put together a new show. Tammen claimed ownership of the name “Buffalo Bill's Original Wild West,” so Cody combined with the 101 Ranch in Oklahoma to create the “Buffalo Bill (Himself) Pageant of Military Preparedness and 101 Ranch Wild West.” He enjoyed the year. His nephew, William Cody Bradford, toured as his assistant. Cody rode in the saddle again, shattering amber balls with his rifle from horseback as he had in days gone by.

Even now he struggled for the ambivalent middle ground. The country was fiercely divided on the subject of American neutrality. Military preparedness was a conservative slogan of those who favored U.S. intervention in World War I, on the side of Britain and France. When the new show played Chicago, home to thousands of German Americans, the proprietors changed the show's name to “Chicago Shan-Kive and Round-Up.” (“Shan-Kive” was said to be an “Indian word” for “good time.”) The event, which resembled a rodeo and featured bulldogging by the likes of legendary black cowboy Bill Pickett, was a huge success.

Outside of Chicago, the show reverted to its Wild West format, with Pancho Villa's raid on Columbus, New Mexico, as its crowning spectacle.

65

The show closed in November. Cody was not feeling well. He arrived in Denver on November 17, “sick with a bad cold and played out from the long hard season,” according to his nephew. He stayed with his sister May for two weeks, then returned to the TE Ranch, where he hoped to recuperate. He continued to fail, and he returned to Denver to seek medical help in the middle of December. His health “was up and down all the time,” recalled Bradford. To the end, he put on a show. “He did not want the papers to get a hold of the news and publish his sickness.”

Cody went to Glenwood Springs, hoping a mineral bath would restore his health. But he returned four days later, none the better. He died January 10, 1917. Louisa was with him, as well as his sister May and her family. Johnny Baker, his longtime assistant and virtual foster son, raced from the East where he had been trying to raise money for the next season's show, but arrived too late to say farewell. Six weeks after Cody died, his longtime press agent, John Burke, also passed.

Cody left instructions to have himself buried on a hill overlooking the town of Cody, but Henry Tammen offered to pay for a funeral if the burial occurred in Denver. Some say Louisa took the publisher's offer to revenge herself on the town of Cody, which she resented like one of her husband's mistresses. Others say she had no money to bury him. In any case, the following June, William Cody was interred in a hole blasted into the summit of Lookout Mountain, overlooking the city of Denver and the Great Plains beyond, as a gigantic crowd of journalists, tourists, and sightseers looked on.

STILL HE RIDES, across our imagined horizon. In the years since his death, he has become, like so many other symbols, detached from his original context, a free-floating icon that may be, and has been, attached to different causes and ideologies. But this process was evident long before he died. By the time 1916 rolled around, Cody had been a theater and arena performer for forty-four years. His face and image, printed on innumerable posters, programs, and other show ephemera, were ubiquitous. He may have been the most photographed man of the period, and although the currency of the Cody face kept him in the public eye, it had a dark side. A person who has been through a historic event, whether a fight on the Plains, the march on Washington of 1963, or September 11, has more historical meaning and authority than has a mere drawing or photograph of that person or event. Reproduced images of authentic people cannot have the authority of real people. A mechanical reproduction, like a photograph, can be put to practically any use its owner can devise, as somber art or decoration, framed portrait or place mat.

Thus, when images of people or landscapes are mass-produced and widely distributed, the authority of the real is devalued. The face, the hair, the pose become symbols with meanings to spectators, but in the process they are often divorced from the history of the person or their setting. Americans who savored the proximity of the Wild West show's real frontier heroes confronted a paradox. They placed images of Cody and his Wild West show in bedrooms, living rooms, and hallways to bring them closer, to claim some element of their frontier authenticity for themselves. But in substituting copies for the unique people and things in the show, and redistributing them in a private arrangement with private meanings, they diminished the power of the very history and tradition which Cody and other real people conveyed.

66

Many of the fans who bought souvenir photographs, books, and programs, to say nothing of Buffalo Bill toy guns, board games, puzzles, tin whistles, dime novels, buttons, and postcards, knew him more from this show business flotsam than from his arena performances. Inevitably, as his fame mounted, he lost authenticity.

67

In this sense, William Cody fomented a mountain of representations of his own face and story to draw a following, then represented himself before crowds who came to watch. The show was not just an adventure of the hinterland. It was a heroic stand of the original against the dead hand of the copy. Cody's optimistic, forthright confrontation with the artifice of modernity, in day-to-day life and in the painted, landscaped, eye-tricking arena which resembled the frontier but whose deceptions evoked the city, made him both the premier symbol of the natural frontier and a hero of artifice among the most modern people on earth. Reproducing his own image and selling it widely was a means of reminding audiences of his importance. But it also meant that by his last decade, the vast majority of his audiences knew him only as a showman with a putative link to the frontier. His ability to generate a flood tide of self-promotion helped ensure his renown. Then it washed him away, like a faded poster in the rain.

The peculiarities of Cody's story, as a popular celebrity who hailed from the frontier West, so confound show business stereotypes that many have suspected, or believed, that he must have been the creation of somebody else. The debate over whether he was a frontiersman or a showman has continued in every Cody biography since he died. But as we have seen, during Cody's life, even as he advanced to ever greater successes, many rivals and partners, from Doc Carver to Nate Salsbury, argued that Cody did not fashion his own success. Against these imputations, Cody partisans, then and now, have maintained that he was a genuine frontier hero who stumbled into fame, an innocent abroad in the world of modern amusements.

But as I have argued throughout this book, neither of these positions illuminates the vibrant culture of artful deception and imposture that characterized nineteenth-century American culture and especially that of the Far West where Cody came of age. True, he was influenced and shaped by many people and forces, but he was neither a simple creation of publicists and press agents, nor was he a lifelong ingenue. In his rise to fame and his long tenure as America's premier showman, his own vision, talents, and burning ambition played the largest role. Hailing from a West that was practically a borderland between real and fake, full of charlatans posing as heroes and of everyday people invited to assume heroic poses, Cody learned the allure of that tense space between authentic and copy, regeneration and degeneration.

Americans imbued that space with a story about the ascent of civilization, and that narrative was so pervasive that settlers easily adopted it as their own, making themselves the protagonists of upward development, from hunting, to ranching, to farming, and commerce. Following that story, and claiming to live it, made Cody's show resonate with public desires, even as audiences might question how real it actually was. Was he a frontiersman or a showman? Clearly, he was both.

In the end, we might say that Cody was partly a trickster, a boundary-crossing figure who appears in the myths of many cultures. Tricksters are usually clowns, monsters, ogres, or spirits. As various scholars have observed, they violate sensual taboos, and societies venerate them partly for the vicarious pleasure they provide. They also destroy old institutions and codes as they erect new ones. P. T. Barnum's biographer, Neil Harris, calls Barnum a trickster because of the ways he loosened the grip of elite knowledge and encouraged Americans to enjoy their own powers of discernment. In elevating western history to a respectable show, in allowing Americans to believe that their frontier fantasies were not only real but embodied in his person, and in providing a means for Americans to accept frontier stories as an art form that was as respectable as any European play, Cody did much to destroy older notions of art and performance, and to usher in a new national mythology for the coming American century.

But tricksters are so dangerous they must be contained in the realm of myth and story. As flesh and blood, Cody could not remain a trickster. The failure of his suit for divorce was, among other things, a signal that he could not violate taboos with impunity. At the end of the day, he had to drape his life in standard morals.

68

Louisa Cody died in 1921, shortly after completing her own memoir of her marriage, a deceptive if not artful book in which she recalled no bitterness, no mistresses, only a warm and loving marriage to the man she helped invent the Wild West show.

69

Many have accepted Cody's publicity that eulogized him as, in his sister's words, “the Last of the Great Scouts.” By this estimation, there could be no more like Cody, because the frontier had passed. While he lived, seeing his show became ever more imperative for those who would witness the fading West.

But if the death of William Cody and his generation of Lakota warriors, American fighters, and scouts severed historical connections between modern America and the frontier of history, there was still another, perhaps more powerful reason why there could be no more quite like Buffalo Bill. This was the demise of the story of progress itself. Indian war was never universally accepted among Americans even while it was going on. But progress, the rise of technology over nature and of settlement over the wild, seemed inevitable. Almost until the year of Cody's death, it was yet possible to believe that western industrial society was the apogee of human development, the beginnings of a more peaceful, humane world, and even to fantasize that one person could embody its promise.