Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (22 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

The cartoon starts from reality, goes through time elapse, increases in nervous tension, all efforts are left too late, but during process of working on her, she becomes more and more twisted and when she arrives at the

Ball she is in a dream. She walks like a dreamwalker, being transported into another world.

This document is also striking for its portrayal of Eliza’s emotional journey through the number on the left against the list of lessons on the right; the passage of time is vivid, and on the back of the paper Holm noted: “‘Workmen’ would change very simple accessories at every re-appearance to signify elapse of time.” Evidently she wanted to create a dark vision in which Eliza became so mentally and physically tortured that she lost track of the boundary between dream and reality.

The following description is Holm’s most detailed and final document of the choreography of the ballet:

Higgins finishes singing [“Come to the Ball”]. Lights come up full. He starts metronome and with sadistic look to Liza goes upstairs in rhythm to the tick of instrument. Entrance of first worker can blend with his exit or he can be instrumental with beginning.

[Part 1]

Workers in 1 part:

Trainer, dance master, cobbler, couturier.

Liza: Depressed, she resents all efforts done to her. Her composure falls to pieces and she has a complete fall back in her old self. She is destructive, uncooperative. Fish arrive, cockney. Speak cockney.

All efforts of “workmen” with no—if not contrary result. Trainer + the dancing master work complementary. Work themselves in a sweat over her with disheartening result. Couturier presents material to inspecting eyes. Cobbler finds unwilling feet. Utter resentment, if not illwill to accept.

She signifies defeat + depression.

After this first amount of “workmen,” they retire in despair, only to return with doppeled effort.

Part 2. Liza. Mechanical acceptance. Pup[p]et-like obedience with neither understanding nor interest. Showing signs of being worked on. Trainer brings helper, couturier brings helper so does dance master + cobbler adding Milliner + make up.

Summing up: no result but more commotion + less resistance.

Part 3. “Workmen” come in greater quantities. More concerted efforts fast + furious throwing her in state of confusion + bewilderment.

Extreme + supreme effort of dancing master to perfect her in curtsey + walk + Valse. Tempo increases to whirling speed of feverish racing against time. Milliner brings head dummy, with hat on which was not finished before.

Cobbler bring finished shoes.

Couturier brings fancy negligee.

Trainer + dance master sweat over their efforts + with everybody helping in their own way, only to leave her limp and with a

through the

will feeling, an end of all resistance (kneaded like a dough to be baked).

After all have left she looks well worked over. Mrs. Pearce enters.

During this entire procedure, she speaks to herself practising speech bits like a pup[p]et with the invisible w[h]ip of Higgins above her.

This outline gives an idea of both the ballet’s structure and its content. Part I is the dance’s exposition: the establishment of its function, and in particular the problems Eliza still faces and which the workmen need to overcome. In the second part, Holm notes that no progress is made, but Eliza is less resistant to the workmen’s efforts. Things work up into a frenzy in the final part, when Eliza is completely overcome and the lessons are completed. It is of note that the literal image of Higgins standing over Eliza with a whip mentioned above has turned into a metaphorical image in this later version.

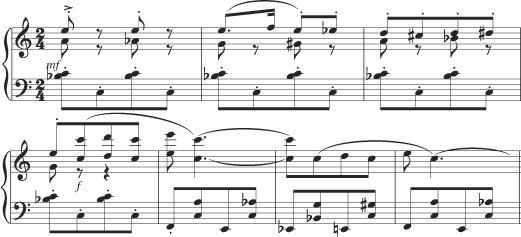

With these choreographic notes in mind, we can approach the musical documents with some idea of the images the score had to accompany. Although it is plain which of the various scores represents the version that was orchestrated and made it to the stage at New Haven, the dance pianist’s copy is also of value for the additional annotations about the dancers’ movements at various points (no doubt to help Freda Miller identify which bars of music went with which parts of the dance). The ballet music started with Rittmann’s eleven-bar “Intro to Dress Ballet” (see

ex. 4.10

); underneath the music, she wrote: “Phil, the above are orchestral exclamations in Higgins’ speech before the dress ballet (no brass).”

33

The music is a simple yet attention-grabbing introduction whose pattern and style—strong accents in the first seven bars followed by the more delicate little scales (slightly reminiscent of the introduction to “I Could Have Danced All Night”)—are not unlike the basic clarity of writing found in nineteenth-century ballet music. Rittmann was lucid in her instructions to the orchestrator: no brass was to be used because Higgins would still be speaking in between the orchestral statements, and the separate parts of the introduction were to be differentiated between by allotting them to alternating instrumental groups. Lang adhered to these instructions almost to the letter whilst adding a little nuance of his own: bars 1–2 and 6–7 were played by strings (and harp) as suggested, but the initial fanfare-type motive in bars 3–5 was given to clarinets, bassoon and horns while bars 8–11 were played by flute, oboe, clarinets, and bassoon (without the horns).

34

Rittmann’s score for the ballet is as fine an example of the dance arranger’s art as could be found. She adheres to themes by Loewe for the majority of the number’s 271 bars, yet makes a fluent composition that is fit to stand on its

own. The ballet begins with a further eight-bar introduction (on top of “Intro to Dress Ballet”) that gives way to a busy expositional passage to accompany the arrival of the Tailor to start work on Eliza. Bars 19–107 are based mostly on two motives from the central section of “Come to the Ball” (the part that returns in “Accustomed to Her Face”):

example 4.11

derives from the line “I

can see you now in a gown by Madame Worth, when you enter ev’ry monocle will crash” in “Come to the Ball”; and

example 4.12

comes from “Little chaps’ll wish they were Atlas, a queen will want you for her son” (which matches the line “She’ll try to teach the things I taught her, and end up selling flowers instead” in “Accustomed”). Rittmann moves freely through keys in her arrangement and goes from

examples 4.11

to

4.12

and back again; this not only reflects the order in which the material appeared in the song—thereby giving the ballet music some structure—but also portrays the music as a ghostly, jumbled-up reminiscence of Higgins’s coaxing words echoing in Eliza’s head. Such a process adds a psychological dimension to the music’s surface task of accompanying the actions of the dancers.

Ex. 4.10. “Intro to Dress Ballet.”

Ex. 4.11. “Dress Ballet,” bars 19–27.

Ex. 4.12. “Dress Ballet,” bars 36–39.

Ex. 4.13. “Dress Ballet,” bars 68–74.

The hairdressers enter at bar 36, then at bar 57 Rittmann changes tack and uses two different motives in quick succession. A hint of the opening line of “Why Can’t the English?” in 68–70 is immediately followed by the “I think she’s got it!” theme from “The Rain in Spain” in 71–74. The effect of this is that Higgins’s song about the inadequacies of education is juxtaposed with his memorable expression of delight at the success of his lessons on Eliza; now she has to aim for the same triumph in a different kind of lesson (

ex. 4.13

). This is repeated a tone higher, then at bar 84,

example 4.12

returns, this time in a much lower register, to herald the entrance of the masseuse. Freda Miller’s score is particularly helpful at this point, marking out gestures such as “prance,” “roll sleeves,” “clap,” and “knee bends.” At the beginning of a rising passage from bar 108, a book is placed on Eliza’s head, presumably to teach her to walk with a better posture, and after the buildup of a repeated accompaniment pattern in double octaves by full strings, the beginning of “Wouldn’t it be Loverly?” is sounded in the trumpets and flute at 120 (

ex. 4.14

).

Ex. 4.14. “Dress Ballet,” bars 120–125.

Ex. 4.15. “Dress Ballet,” bars 154–159.