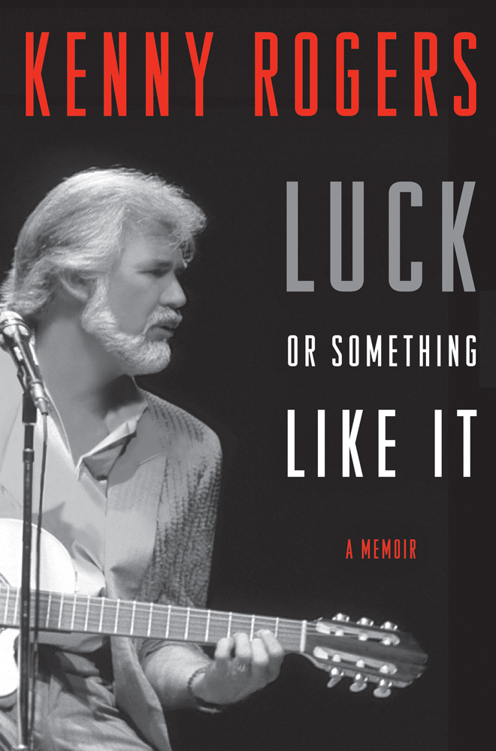

Luck or Something Like It

Read Luck or Something Like It Online

Authors: Kenny Rogers

LUCK

or

Something Like It

KENNY ROGERS

T

O

W

ANDA

, J

USTIN

, J

ORDAN

, K

ENNY

J

R

.,

AND

C

HRIS

.

T

HEY ARE MY ROCK

. T

HEY ARE MY REASON FOR LIVING

.

Contents

Chapter One - A Pair to Draw To

Chapter Two - Music and Country

Chapter Three - Lovesick Blues

Chapter Six - Where It All Began . . . Jazz

Chapter Seven - It’s Not All Wet Towels and Naked Women

Chapter Eight - Just Dropped In

Chapter Nine - Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town

Chapter Thirteen - The Good Life

Chapter Fourteen - A Life of Photography

Chapter Fifteen - Around the World

Chapter Sixteen - After the Gold Rush

Chapter Nineteen - Looking Back

I would like to

offer a special thanks to my friend, Patsi Bale Cox. Without her, this autobiography never would have happened. I had been asked to do a book for at least twenty years, and it was never something I had any interest in doing, for a lot of reasons.

After being persuaded to meet with Patsi for lunch, I found myself discussing and laughing about moments of my life that I hadn’t thought about for years. In that moment, two things happened: I agreed to write the book and I made a new friend. Both were exciting.

Somewhere in the middle of our journey together, Patsi was diagnosed with a form of lung cancer, and I think she knew in her heart it wasn’t going to end well. Instead of stopping and feeling sorry for herself, she committed herself to the completion of my story.

There were times when she couldn’t type or talk on the phone and when she could barely breathe, but she tried. She worked as hard as she could to live up to her responsibility to me and the publishers, but this disease shows no favorites. On November 6, 2011, the disease won the battle. She had fought it with all she had . . . and lost.

She wasn’t fighting so much for me but for what she thought I had to offer to the history of country music. Her first love was music history. As we go on without Patsi, I hope we can do her memory justice and live up to what she had hoped to accomplish in her mission.

I, and all of country music, will dearly miss our friend Patsi Bale Cox.

Special thanks to Allen Rucker for stepping in at an awkward moment and for pulling this whole thing together. Without him, it never would have been finished.

I’d also like to thank Jason Henke for his important contributions to this book. Jason’s tireless efforts, attention to detail, and knowledge of my career were vital to getting this book to where it needed to be.

In addition, I would like to thank Matt Harper at HarperCollins for his unwavering dedication to this project. Matt took remarkable care at every turn to ensure a successful arrival at the finish line, and I’m grateful for all of his hard work.

Special thanks also goes to Kelly Junkermann for his help writing this book, for remembering all the good times we’ve had together, and for taking so many of the terrific photos in this book.

Finally, this book never would have happened without the two people who got the whole process started. Many thanks to Lisa Sharkey at HarperCollins and Mel Berger at WME for helping to convince me that the time was finally right for me to tell my story.

“What in the world

were you thinking, Kenneth Ray?”

My mom was on the phone. It was in the early months of 1977 and she had tracked me down on the road. Things had been moving so fast with the release of my new single that I hadn’t talked to her in a while.

“The very idea! What are people going to think when they hear you singing about your mother leaving her family to run off to some bar?”

I couldn’t get a word in edgewise. My mom was on a roll.

“And how dare you write about me having four hungry kids?”

The song was, of course, “Lucille.” And as a matter of pure coincidence, my mother’s name was Lucille. She had not been amused when she heard those lines coming over the radio airwaves: “You picked a fine time to leave me, Lucille, with four hungry children and a crop in the field.”

“Mom, Mom,” I said. “First of all, you have eight kids. Secondly, it’s not about you. And thirdly, I didn’t write it.” I paused for a moment, and my mom jumped back in.

“Imagine what your father would say!” My dad, if he’d still been living, would’ve been having a good time with this one. He really loved to watch my mom squirm.

For a man who had lived a tough and often disappointing life, he could find something funny in nearly everything. My mother had a sense of humor, too, but I could tell she wasn’t having fun with this song I’d recorded.

Earlier, I’d told her the story about the song “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town,” and how the country star Mel Tillis had written it about a real person. So as far as she was concerned, this new song might be close to character assassination for a woman named Lucille.

And she wasn’t the only doubter.

Some of the label executives had questioned the song when they first heard it, thinking it was all wrong for a Kenny Rogers release. But then, the top brass at United Artists had considered me a long shot as a country artist to begin with. It wasn’t surprising that a major label might question offering a country contract to a former jazz and rock musician who was closing in on forty years old. For that guy to make it in country, he’d have to beat some big odds.

In fact, Al Teller, the head man at UA, had told my Nashville producer, Larry Butler, to forget this outrageous idea of signing Kenny Rogers and instead sign some guy without a twenty-year history. Butler, being something of an outrageous character himself, said, “Read my contract, Al. I can sign anyone I want to.” There was dead silence on the phone. “Hello?” Butler asked.

“You better be right,” Teller snapped, and slammed down the phone.

That was the end of the signing debate, and after UA heard our first studio work, they jumped on the bandwagon. But over a year later, we still hadn’t found the breakout song. Two singles—“Love Lifted Me” and “Laura (What’s He Got That I Ain’t Got?)”—had cracked the Top 20, but the one big release that would establish me firmly in country music was elusive. I agreed with Larry Butler that “Lucille” could be big. I did question the original ending, thinking it was a downer. But after some rewriting of the last verse, I thought we had a song that worked for me and would fly on radio as well.

When my manager, Ken Kragen, first heard the song, he burst out laughing. “This will either be written off as a novelty song,” he said, “or it’s going to be the biggest song in the country.” It was a good thing he gave it at least a fifty-fifty shot, because, once again, the UA execs disagreed. They thought it was “too country” for what they considered my middle-of-the-road image. Of course, when I’d walked in the door, I wasn’t country enough. I couldn’t win. This time it was Kragen who stepped in.

“Release it,” he said. And they did.

After one performance of “Lucille” on the

Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson,

Butler got a call from Atlanta: “We just got a reorder for ten thousand copies of that single.”

“What?”

“You heard right—ten thousand.”

Butler called me and said, “It’s exploding.”

Seemingly overnight, we went from two shows on weeknights and three on Sunday in Las Vegas lounges to the main showrooms. Things moved fast. It seemed like just a couple of weeks earlier, our road manager, Keith Bugos, was having to get to our shows early to make sure someone hadn’t mistakenly put up an old Kenny Rogers and the First Edition poster or gotten me confused with Kenny Loggins, who was just beginning a solo career separate from Loggins and Messina. Keith also had to deal with the fact that we only had the sound equipment for an audience of two to three thousand. Now the venues had overflow crowds of ten thousand.

“Lucille” changed everything. It went to No. 1 and stayed there for two weeks. It won a Grammy, the Academy of Country Music Song and Single of the Year, and the Country Music Association Single of the Year. In 1977, I was named the ACM Male Vocalist and in 1978 took home that honor again along with the ACM Entertainer of the Year. But maybe the most telling awards came from the jukebox operators, because jukebox sales reflect people going into cafés, drugstores, and bars, dropping their quarters into the slot, and paying to hear a song. It was listeners like that who grabbed ahold of “Lucille” and made it a monster hit.

Once “Lucille” became a worldwide hit, it didn’t bother my mom that she happened to have the same name. It didn’t have to be about a real person just because “Ruby” was. My mom was nothing if not pragmatic.

More important, she wanted me to be happy and to succeed at whatever I tried. She was never one of those people who drilled it into her kids’ heads that they could do anything they set their minds to, but she did believe life was full of possibilities. You just had to be open to opportunity when it showed up.

My mom saw lessons in almost every experience. She had advice for nearly any situation, and it was one of the old adages she so loved that convinced me making music was the life for me: “Find a job you love . . . and you’ll never work a day in your life.”

One time a journalist asked her if she was proud of me, and she said, “You know, I’m truly proud of all my sons. My other boys had jobs Kenneth probably couldn’t do. . . . All that boy ever did was sing.”

“Kenneth . . . Kenneth . . .

Kenneth Ray!”

That sound still rings in my ears when I think of my mom. Like most kids, I could usually count on being in trouble when my mom used both my names together like that. So I ask you: Why would a mother yell this name at her son all his life, after signing a document that says his name was Kenneth Donald? I ask because I actually saw the birth certificate with my mom’s and dad’s signatures, which I recognized as theirs, with the name Kenneth Donald on it

,

and I had never, ever heard anyone in my family call me by that name. It was always Kenneth Ray.

I was born on August 21, 1938, at St. Joseph’s Infirmary in Houston, Texas, the fourth child of Edward Floyd and Lucille Lois Hester Rogers. I am told that I have Irish and Native American heritage, and I always assumed that my Native American blood came from my grandmother Della Rogers, with her high cheekbones and her once dark black hair that she pulled back in a severe bun in her later years. Whether it was Grandmother Della or someone else, I can’t say for sure, but I just took it for granted that I was part Irish, part Indian, and that was that.

I grew up in the San Felipe Courts housing projects of Houston’s Fourth Ward. San Felipe Courts, which was later renamed Allen Parkway Village, was built by the city of Houston in the early 1940s. San Felipe Courts consisted of a series of long, two-story brick buildings that faced inward to a courtyard with benches where people gathered to talk and children played. Over the years, many journalists have listed me as growing up in the Houston Heights area, but it was actually San Felipe Courts. The Heights was more upscale than my family could afford.

We were poor people, but living in the projects, we really didn’t know it because we were all in the same boat. Our apartment had two bedrooms upstairs, one downstairs, and a kitchen. We basically had a revolving door with people always coming and going; as the older kids moved out, the younger kids came in. I was closest to my sister Barbara, who was two years older than me. The problem was that she beat me up every day of my life. Finally, the day I reached the breaking point, I had her by her hair and was banging her head on the fridge door. Thank God my dad walked in when he did or I would have killed her. Barbara could be both my best friend and my worst enemy.

My brother, Lelan, was ten years older and was gone all the time. Lelan was really slick, smooth talking, a very sharp dresser with his hair slicked back, and one thing was for sure—he knew the streets. Lelan left home at seventeen. My sister, Geraldine, was thirteen at the time, and my sister, Barbara, was nine. My younger brother Billy was four, and Roy was just a baby. At this point the twins, Randy and Sandy, weren’t born, but we knew with Mom and Dad, more were coming.

No matter what age we were, our parents would send us outside to play. They had no worries about us being harmed by strangers. We played all over that area of town with no fear. Seems hard to imagine now, and I regret, for most kids today, both that loss of innocence and that loss of freedom.

Prior to the time the city built San Felipe Courts, the Fourth Ward area had been primarily African American, including Freedmen’s Town, so named because freed slaves had populated it in the late 1800s. The land was cheap because much of it was low swampland prone to flooding. Initially, there were rumors that African Americans were going to be included in parts of this public housing, but after the Courts were built, the city put up a fence between the Courts and what was left of the black section. At that young age, I didn’t know why people were separated or even think to ask. It was just the way things were. I’m sure there must have been some bad feelings among the African Americans about that fence, but I never felt any hostility. I spent quite a bit of time in the black section, going to the friendly, always welcoming Italian store, Lanzo’s Grocery, for my mom or cutting through the yards on my way to school, and my memories were of friendly faces, elderly people sitting on their porches and waving as I passed. I’d like to think I’ve always been color-blind, and my relationship with the people in the black neighborhood next to San Felipe Courts is probably the reason. I can only speak for my family, but in our case, we were all poor people and felt a certain kinship.

Parents know their families are poor, but kids don’t until rich kids at school notice. And they did notice and were quick to make fun. My defense was developing a lifelong habit of blocking out painful memories. Not too long ago, though, I got a letter from a grade school friend that brought back one very hurtful moment. Her name was Mary Gwynne Davidson (now Ridout) and we were in the first grade together. She remembered me as someone who kept to himself and was very quiet and very polite. And very self-conscious, I might add.

The occasion that Mary Gwynne remembered was an event in Mrs. Monk’s first grade class called May Fete. The tradition was that each girl got to pick a boy as her May Fete partner. For a six-year-old, this was a big deal, and Mary Gwynne has been kind enough to let me share her letter here:

It was April of 1944 in Mrs. Monk’s first-grade class at Wharton Elementary School in Houston, Texas.

We were lined up, girls in alphabetical order. The teacher had given us instruction for the girls to select their May Fete partner. My last name was Davidson so I was close to the beginning of the line, which gave me a pretty good position. I remember clearly that I selected Walton Elson for my partner.

I then watched as one by one the other girls selected their partners. It became very clear to me that a shy blond boy was going to be the last choice. The girls in the line had begun to snicker and talk about Kenny as he didn’t have any shoes and wore black-and-white-striped overalls. Kids can be so cruel.

I watched as Kenny fidgeted and tried to not show his embarrassment. He was very polite and kept up a brave front, even with all the snickering. His mannerism was very gentle. I began to try to imagine how he must have felt. It hurt!

Kenny was from a family of nine or ten children and lived in a tenement district in Houston called San Felipe Courts. He helped his mother support his brothers and sisters by selling newspapers on the street corner and doing odd jobs that a young lad could do. In his adult life Kenny’s mom moved to Crosby, Texas, where Kenny built an adult center where seniors could go and socialize and enjoy life. I understand he provided everything they might need to enjoy their leisure time together and that he also provided for food for the needy in the community.

In 1962 I ran into Kenny again at a little place called “The Coffee House” on Bellaire Blvd. across from the Shamrock Hilton Hotel. He was playing bass fiddle with the Bobby Doyle Three. Bobby played piano and sang, but that night Bobby had a really bad cold and in the middle of a song he stopped and said, “I have punished my throat and my audience enough. We will now find out if these other guys can sing . . . Kenny, it’s your turn.” When Kenny sang, I knew he “HAD IT.” Yes, he had what it takes to make it because Kenny is none other than Kenny Rogers, my old May Fete partner and friend.

Wishing you well . . . you deserve it. I’ve always admired you . . . your classmate and friend.

MARY GWYNNE DAVIDSON RIDOUT

It did hurt. It took Mary’s letter to jar my memory about this particular incident, but I never forgot the pain.

We were always short on money. Meals were usually simple poor-folks food: pinto beans and rice, corn, and collard greens that we picked with our mom along the banks of Buffalo Bayou.

Thinking back, I never had the feeling that our mom really enjoyed cooking. She worked too many jobs and had too many kids to see preparing meals as much more than a daily chore. She worked as a nurse at Jefferson Davis Hospital, and she worked cleaning offices at the Gulf Building; on Sunday, she worked at the church. As for cooking, she

was

proud of her banana pudding, and she did love to sit and have a glass of iced tea.

My dad was easy to please when it came to food. He was truly happy as long as there was a mason jar full of long jalapeños on the table. Every night he’d crumble his beans and rice with a fork, take a bite, then grab a jalapeño and bite it off at the stalk. He would literally break into a sweat, his face turning so red it looked like it was on fire. He couldn’t utter a word for a while after each one. I watched him do that over the years and never failed to marvel at his ability to eat those things. I tried it once or twice and that was it. Once, in grade school, I finally asked him why he ate them. He just smiled, and as soon as he could talk again, he said, “I just love ’em, son. I just love ’em.”

Remembering my father is important to me, but it’s also painful. I actually knew little about him. Like most men of his day, he was pretty shut down. That was hard, but what was really difficult was that he did not have a happy life and he drank to bury his feelings about it. My older brother, Lelan, once described him as a bitter man. I think that the Floyd Rogers Lelan knew and the one I knew were different, though; by the time I really got to know my father, he seemed more beaten down than bitter.

My dad was an alcoholic, and alcohol costs money—money we didn’t have, money that should have gone to buying food and clothes. Drinking controlled his life, and he was always looking for a way to pay for it. After Lelan had left home, my dad would always hit him up for some cash when he came for a visit, sticking out his hand and saying, “Will this be a ten-dollar or a twenty-dollar visit?” It was his game, and we always knew it was coming.

On one occasion when he panhandled Lelan, Lelan snapped back, “You know what, Dad? That question really offends me. I spent a hundred and fifty dollars on a plane ticket to come here. I rented a car in Houston, drove here to Crockett, and took you and Mom out to dinner. Next time would you rather I just send you the money and not come at all?”

My dad thought this over and finally got a little grin on his face and said, “Oh God, son. Don’t make me make that choice.” He would’ve hated to admit it, but I think he was truly conflicted over that question.

When I was older and started making a little money, my dad began to treat me the same way—as the golden goose. It evolved into another game he would play to get liquor money. He would start out talking about money in general.

“If I could just get together a hundred dollars . . . ,” he’d say.

Or he might mention something specific, like “If a man just had an electric saw.”

I’d play along. “So if this hypothetical man had an electric saw, what would you saw with it? Would you build anything?”

Usually my questions didn’t get much of a response, but one time my dad said, “I’d build birdhouses.”

“Really!” I said. “What’re you going to do with them? Put them in the yard?”

“No, I’m gonna sell birdhouses.”

“How many of them could you make in a day?”

My dad shrugged. “I don’t know. Two or three.”

“So at the end of the week you’re going to have maybe twelve or fifteen birdhouses. Where are you going to sell them?”

“Somewhere, maybe on the street.”

“What if it’s raining? Or are you just going to sell them in good weather?”

“Well,” he’d say, “hell, son, I don’t know!” and off he’d go with some new on-the-spot cockamamie plan. “If a man had a violin . . .”

He knew I was just messing around, but he really did want the money. We both knew it, and we also knew that I would end up giving him money even though I knew I shouldn’t because of the drinking. I knew it enabled him. When he brought a paycheck home, if my mom got ahold of it quickly enough, she kept the money to help pay household bills. This was painful to watch because I knew my dad felt completely emasculated at those moments, and I hated seeing him like that. Between us, it was just a couple of guys kidding around. But when my mom stepped in, he felt like less of a man.

Someone once brought to my attention that every time I spoke of my father, the first thing I’d say was “He was an alcoholic.” He was an alcoholic, for sure, but the guy then asked, “Was that the most important thing about your father?” That stopped me in my tracks, because suddenly I realized that he was right. Though his alcoholism was a destructive constant in our lives, it was only a part of my father’s personality.

For one thing, he was a damn good fiddle player and, for another, he was a damn good storyteller. Although his drinking certainly hurt him, I don’t think it left any of his kids permanently damaged. I’m sure my mom didn’t love this side of him, but she loved him. Unlike many couples today, when things got bad, they didn’t split up. They stayed together. And honestly, he was the best father he could have been, given his addiction and his inability to find a steady job.

I certainly couldn’t say his drinking ruined my life or the lives of any of my brothers and sisters. If anything, it kept me from any real degree of substance abuse. I never wanted to get out of control like I saw my dad and his drinking buddies do back in the projects. My dad never beat us and was never violent on any level. He was in fact a good-natured drunk, except when he would argue with his best friend, Mr. Knoe, another alcoholic who lived across the courtyard from us. They’d get into it and yell at each other for hours, then stagger off home to sleep it off. By morning they’d both have forgotten they even argued the night before. It was never about anger with my dad. His drinking and his all-night arguments were about frustration and disappointment.

My father was never much of a disciplinarian. I only remember a few times when he punished any one of us. One occasion involved my younger brother Roy and my dad’s precious liquor stash at home. My dad hid his liquor in one of the closets, where one day Roy happened to find a bottle. He knew that the minute our dad got finished with dinner, he would slide into the closet, close the door, and take a big hit from his bottle of whiskey.