Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (2 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

CHAPTER ONE

THE TIGER AND THE HEDGEHOG

WHERE WAS GEORGES CLEMENCEAU?

The day of the French election had arrived—Sunday, April 26, 1914—and the newspaper

Gil Blas

announced in astonishment that the seventy-two-year-old former prime minister had disappeared from Paris. “His departure does not fail to cause surprise,” reported the paper. “Is this vigorous polemicist no longer interested in the political battle?”

1

Gil Blas

was always remarkably well informed about the comings and goings of Clemenceau, whose fearsome personality had earned him the nickname the Tiger. Two years earlier the paper had reported how firefighters came to Clemenceau’s rescue when his bathroom caught fire as he took a hot soak; another time it informed readers how, despite the fact that he was France’s most notorious anti-Catholic, he had recuperated from an operation at a convalescent home run by nuns.

2

And indeed, on this occasion, the paper quickly managed to track him down, reporting that he had gone to enjoy springtime in the countryside. “It is whispered that he wants rest at all costs, and that, little concerned with electoral results, he will sleep late, in rustic silence.”

Clemenceau’s rustic retreat was fifty miles northwest of Paris, in the Normandy village of Bernouville. Six years earlier, while still prime minister, he had bought a half-timbered hunting lodge whose garden he planted with white poplars and Spanish broom, and whose ponds he stocked with trout and sturgeon. A few weeks after he left office in the summer of 1909,

Gil Blas

ran an admiring poem describing how, “spry as a stripling,” he was hard at work in his garden.

3

It was no doubt this love of gardening that, as the election loomed, drew him to Bernouville and that, so he could talk flowers instead of politics, then took him to Giverny to see his friend, the painter Claude Monet.

*

GIVERNY WAS TWENTY

miles from Bernouville, but the chauffeur would have covered the distance quickly: Clemenceau, who loved speed, always urged his drivers to go faster, racing along bone-shaking country roads at speeds in excess of 100 kilometers (62 miles) per hour.

4

He often unhooked the speedometer to allay the alarm of his passengers.

5

The car would have entered the tiny village of Vernonnet and then, as it reached the right bank of the Seine, turned left for Giverny along a road bordered on the right by meadows and, on the left, by the steep flank of a hill. The hill was gouged with whitish streaks from sandstone quarries and sown here and there with vines that produced the local vintage. To the right was the river Ru, a thin rivulet in which, not long ago, a visiting journalist had marveled at the sight of washerwomen.

6

Beyond, a line of tall poplars snaked across meadows that in May were stippled by poppies and that in autumn were populated by towering stacks of wheat.

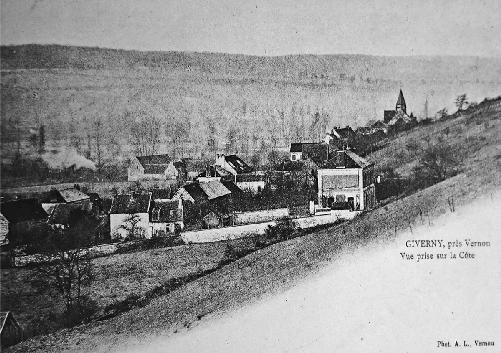

A couple of miles from Vernonnet, a cluster of houses suddenly appeared. Clemenceau’s driver would have swung left at the fork, heading toward a small church with a squat, octagonal tower and a black witch’s hat of a steeple. Giverny was a village of some 250 inhabitants, with one hundred or so rustic cottages interspersed with more imposing homes set in orchards behind moss-covered walls.

7

The effect, especially for someone coming from Paris, was magical. Visitors unfailingly described Giverny as charming, quaint, picturesque, and an “earthly paradise.”

8

One of Monet’s visitors later enthused in her journal: “This is the land of dreams, the realization of a fairyland.”

9

Monet had first arrived in Giverny three decades earlier, at the age of forty-two. The village was forty miles as the crow flies northwest of Paris, in the valley of the Seine. In 1869 a set of railway tracks had appeared beside the Ru, and a railway station sprouted in the shadow of the two windmills on Giverny’s eastern outskirts, where the willows lazily arranged themselves over the riverbank. Soon four trains were puffing through the village every day except Sunday. Early in the spring of 1883, one of them carried a house-hunting Monet. He was then a widower with two boys to think about, along with a middle-aged mistress

and her own brood of six children. From his seat he watched, entranced, as the steam train hissed to an unscheduled halt beside a wedding party waiting by the side of the road. Led by a violinist, the newlyweds and their guests happily embarked, oblivious that their festivities decided the painter on his domestic surroundings.

10

Postcard of Giverny in Monet’s time

A short time later, Monet and his blended family took possession of one of the largest homes in the village, an old farmhouse known as Le Pressoir (the Cider Press). For the next seven years he rented the property from Louis-Joseph Singeot, a trader with dealings in Guadeloupe. Pink with grey shutters, it overlooked on its north side the rue de Haut (High Street), and on its south side a walled garden planted with vegetables and an apple orchard. Monet soon painted the shutters green, a color that quickly became known in the village as “Monet green.”

11

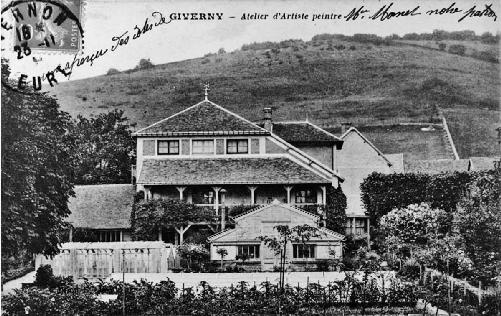

For a studio he took over a dirt-floored barn connected to the house. In 1890, a few days after his fiftieth birthday, he purchased Le Pressoir from Singeot, adding an adjoining plot of land a few years later. He began

uprooting the vegetables and apple trees, replacing them with irises, tulips, and Japanese peonies. On the northwest corner of the property he constructed a two-story building—described by one visitor as a “rustic pavilion”

12

—on whose top floor he arranged a high-ceilinged, skylit studio. On the ground floor was an aviary stocked with parrots, turtles, and peacocks, as well as a photographer’s darkroom and a garage for his collection of motorcars.

Postcard of Monet’s second studio with the greenhouses in the foreground

The large house, the light-filled studio, the fleet of automobiles—such luxuries had come late. Monet’s early years as a painter occasionally featured irate landlords and shopkeepers, out-of-pocket friends and enforced economies. “For the past eight days,” he lamented in 1869, aged twenty-nine, “I’ve had no bread, no wine, no fire for the kitchen, no light.”

13

That same year he claimed to have no money to buy paints, and bailiffs seized four of his paintings from the walls of an exhibition to settle his numerous debts. Over the next decade his canvases sometimes went for as little as 20 francs each—at a time when a blank canvas cost 4 francs. He was once forced to give paintings to a baker in return for

bread. A draper proved “impossible to appease.” His laundress sequestered his bedsheets when he failed to pay her bill. “If I don’t come up with 600 francs by tomorrow night,” he wrote to a friend in 1877, “my furniture and all I own will be sold and we’ll be thrown into the street.”

14

When a butcher sent round the bailiffs to impound his possessions, Monet vengefully slashed two hundred of his canvases. He once, so the legend went, spent a winter living on potatoes.

15

Monet often exaggerated his plight. Even in the early days, his paintings had sometimes attracted astute collectors and fetched respectable prices. In 1868 the esteemed critic Arsène Houssaye paid 800 francs for one of his paintings—enough to pay the rent on a house for an entire year. Moreover, his privations were offset by generous friends: the painter Frédéric Bazille; the novelist Émile Zola; a pastry chef and novelist named Eugène Murer; and Dr. Paul Gachet, who would later have on his hands another frustrated and even more impecunious artist, Vincent van Gogh. All of them, over the years, received begging letters detailing Monet’s allegedly precarious financial state and his miserable prospects. In 1878, aged thirty-eight, he lamented to another benefactor, Georges de Bellio, a homeopath: “It’s sad to be in such a situation at my age, always obliged to ask for favours.” Then, a few months later: “I’m absolutely disgusted and demoralized by this existence that I’ve led for such a long time...Each day brings new sorrows and new difficulties from which I’ll never extricate myself.”

16

Monet’s career had actually begun with great promise. In 1865 his two views of the Normandy coast caused a sensation at the Paris Salon: one critic called them “the finest seascapes seen in recent years,” while another declared them the best in the entire exhibition.

17

However, the following years proved difficult as subsequent works—whose blurry images and seemingly casual brushwork violated prevailing conventions—were regularly spurned by Salon juries. His critical notoriety seemed to be sealed when, in 1874, he showed work in Paris with a group of artistic rebels who included Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Paul Cézanne. They were pejoratively dubbed “Impressionists,” with one of Monet’s seascapes mockingly denounced as “less skilful than

crude wallpaper.”

18

Conservative critics condemned his paintings as “incoherent,” as “false, unhealthy and comical” and as “studies in decadence.” “When children amuse themselves with paper and crayons,” sniffed one of his critics in 1877, “they do a better job.”

19

Monet kept a scrapbook of these reviews—a veritable catalogue, a friend observed, of “shortsightedness, ignorance and indifference.”

20

An 1880 interview called him “one of those wild beasts of art.”

21

A collector who bought one of his canvases was so ridiculed by his friends that, according to Monet, he removed the work from his wall.

22