Madame Blavatsky: The Woman Behind the Myth (57 page)

Read Madame Blavatsky: The Woman Behind the Myth Online

Authors: Marion Meade

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs

Irish poet George Russell, 1930. "A.E.'s" work was deeply influenced by H.P.B.'s philosophy, particularly by

The Secret Doctrine,

robert h davis, photographer. New York Public Library picture collection.

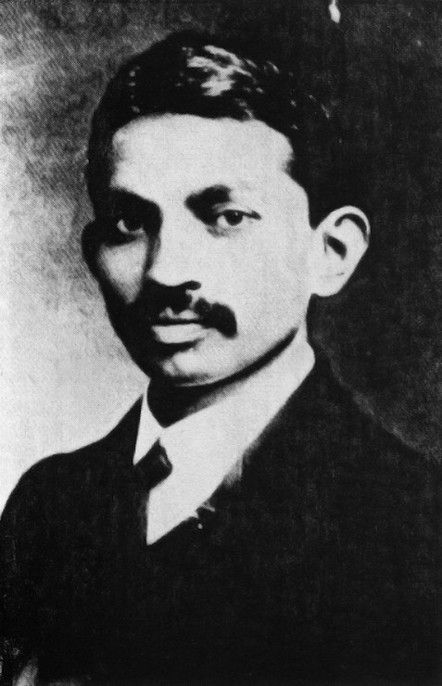

Mohandas K. Ghandi as a young lawyer in East Africa. Earlier, while a student in London, the future Mahatma first read the

Bhagavad Gita

at the suggestion of two of H.P.B.’s disciples. New York Public Library Picture Collection.

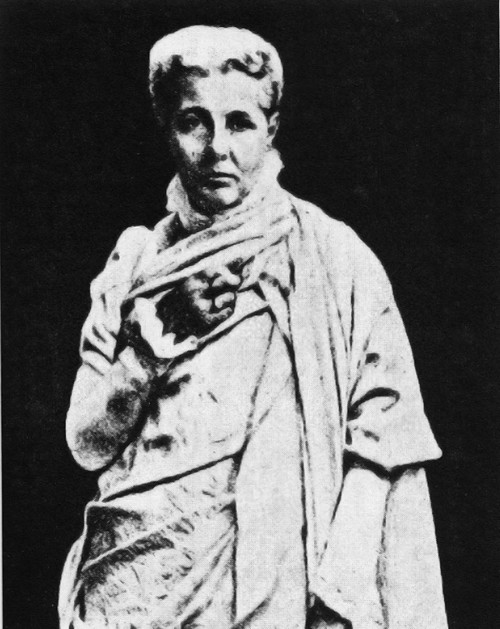

Annie Besant in about 1897, age fifty. H.P.B.’s chosen successor, she became president of the Theosophical Society after Colonel Olcott’s death. New York Public Library Picture Collection.

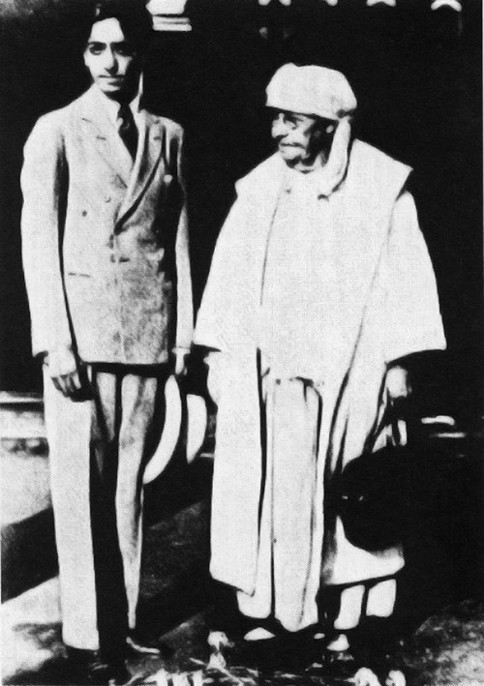

Jiddu Krishnamurti and Annie Besant in the 1920s. Mrs. Besant hailed him as the avatar of the New Messiah. UPI

Garlanded Jiddu Krishnamurti and Annie Besant returning to India in 1927 after a long tour abroad. “I have seen Buddha, I have communed with Buddha, I am Buddha,” he said then. Two years later he resigned from the Society. Wide World Photos.

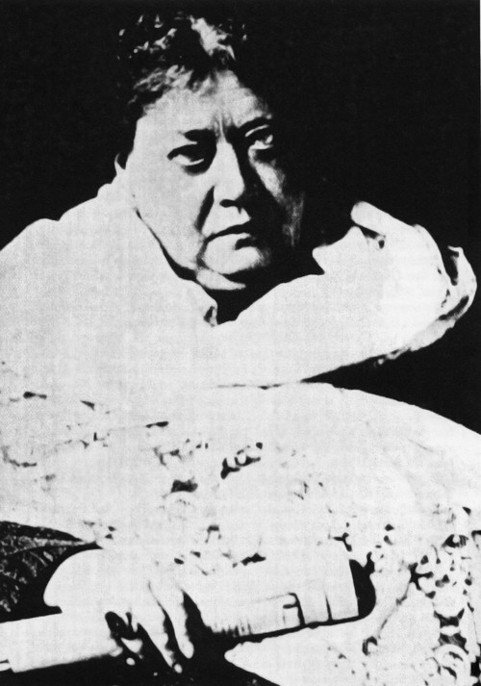

H.P.B. in London, 1889. New York Public Library picture collection.

EUROPE

1884

I

Paris

The sea voyage seemed exceptionally calm and pleasant to Helena, even though the first day out Mohini and Babula “brought up their dinners for the whole year 1883,”

1

while she suffered not a single minute of seasickness. In fact, her health improved so drastically once they left Bombay that Henry remarked on her miraculous recovery. They had day after day of fine weather, but Helena sat cloistered in the captain’s quarters, working on a French translation of

Isis Unveiled.

By the time they reached Suez, she had almost finished the first volume. She would have been completely relaxed if not for Olcott’s angry nagging about her extravagance; specifically, one particular bill of which he had learned shortly before leaving Bombay: apparently she had taken seven hundred rupees from the communal account and spent it on her personal suite. At Suez, Henry wrote to Alexis Coulomb that he was “tired of this haphazard, unsystematic and compromising way in which our whole financial affairs have been conducted,”

2

and that Madame Blavatsky had promised to assume total financial responsibility for her own quarters in the future. His continued harping on money bored Helena, and when he told her of his reticence about accepting St. George Lane-Fox’s offer to endow the Society “lest... in becoming rich... it... should become vicious and proud,”

3

she tossed her head in furious frustration.

Arriving at Marseilles on the twelfth of March, she was greatly exasperated at being quarantined for twenty-four hours because of, as Henry called it, “the sanitary sins of Bombay.”

4

Not until the following day were they able to continue on to Nice where they were met by Lady Marie Caithness, Countess of Caithness, and Duchess de Pomar. A year older than H.P.B., Lady Marie was a Spaniard who had survived two husbands to become an extremely wealthy widow with palaces in Paris and Nice. Now she had begun to use her fortune to finance her interest in occultism. Both a Spiritualist and a Theosophist, she believed herself to be a medium for the spirit of Mary, Queen of Scotland, who “came through” in automatic writing and at the weekly seances Marie hosted at her Paris palace, appropriately called Holy-rood. Lady Caithness was a singularly charming woman renowned for her kindness and boundless hospitality, and when H.P.B. arrived in France, Lady Caithness was so pleased to meet her that she insisted upon underwriting many of her expenses.

At Nice, Mohini and Padshah were sent on to Paris while Helena and Olcott got a taste of fashionable Riviera society at Lady Marie’s Palais Tiranty. Marie did everything in her power to make them feel at home by arranging soirees for vaguely noble locals to meet Madame, but Helena found her energies sapped by a host of minor maladies. Upon landing at Marseilles, she had suffered an upset stomach and then, dragged to the theater one evening, she felt so exhausted that she slept through three acts and caught a cold that turned into bronchitis. As if that were not aggravating enough, she suddenly erupted with “gum boils, neuralgia, rheumatics and sciatica, with fever in my ears and diphtheria in my toes.”

5

Gum boils notwithstanding, she was immensely pleased to find a colony of Russian aristocrats wintering in Nice, among them a Dolgorukov cousin and a woman Helena had played with as a child at Saratov. “She knew me by name, having heard of my felicitous marriage with old father Blavatsky, and fell this morning into my arms weeping and wiping her nose on my sympathetic bosom,” wrote H.P.B, but she was clearly delighted to be carried off to their palaces for dinners and luncheons, “accepting my dressing gowns and evening deshabilles, cigarettes and compliments with a Christ-like forbearance doing great honour to their patriotic feelings.” Everyone invited her to visit them in Russia, to which she commented cynically in a letter to Alfred Sinnett, “I wish they may get it,”

6

and they gushed over the picturesque Babula whom H.P.B. had dressed in flaming yellow livery and earrings. Helena jokingly remarked that before going to Paris she would have an extra earring put in his nose.

In the meantime she was not surprised to see dribbling in a half-dozen invitations from London Theosophists: Francesca Arundale, Isabelle de Steiger, the Sinnetts, and others whom she had never met were all urging her to visit. Since the letters were obviously sincere, she devised a standard reply saying that although she was deeply touched, they nonetheless must not expect her. She was crumbling into pieces like an old sea biscuit, she quipped, and “all that I hope to be able to do is mend my weighty person with medicines and will-power and then drag this ruin overland to Paris.” Besides, she was not fit to meet civilized people, for “in seven minutes and a quarter I should become perfectly unbearable to you English people if I were to transport to London my huge, ugly person. I assure you that distance adds to my beauty...”

7

Nobody agreed more emphatically with those last words than Alfred Sinnett, who was privately bewailing the appearance in Europe of both H.P.B. and Olcott. After his departure from India, Sinnett had hurried back to London, where he had established a Theosophical Society to his own taste and proclaimed himself the only true bearer of the Mahatmic message. Having been hobnobbing with a fashionable circle of wealthy intellectuals whom he had drawn into the T.S., he regarded the arrival of the founders as a mammoth embarrassment. Still, he was left with no alternative but to make the best of it.

Helena, despite her protestations, had every intention of appearing in London, but it would happen in her own newsworthy way. On the other hand, she felt sick and cross in Nice, partly from her cold and from other ailments she herself recognized as psychosomatic. Now that she had made the long trip from India, she began to dread facing the English Theosophists whose members had such small compunction about publicly insulting her and the Mahatmas. For over six months, while writing civil replies to Anna Kingsford, she had “accumulated bile and secreted gall,”

8

and now she was about to explode like a bombshell. “I

cannot

keep calm,”

9

she warned Sinnett.

H.P.B.’s private turmoil remained well hidden from Lady Caithness and the Russian women, who continued to humor her extravagantly, urging her to remain in Nice until at least May. After two weeks, though, H.P.B. and Olcott moved on to Paris, where Lady Marie had put at their disposal, gratis, an apartment at 46 rue Notre Dame des Champs. With an eye to making an impressive arrival, H.P.B. had taken care to arrange a reception for herself; it was Koot Hoomi who had suggested the choreography in a letter to Mohini at Paris: “Appearances go a long way with the ‘Pelings.’ One has to impress them externally before a regular, lasting, interior impression is made. Remember, and try to understand why I expect you to do the following.”

10

When

Upasika

arrived, Mohini was to salute her by throwing himself flat on the ground and bowing his head. As if anticipating that even Mohini might be reluctant to make a public fool of himself, K.H. advised him to ignore the stares of the French and of Olcott, who would surely want to know what was going on. This was a test, K.H. was at pains to warn; the

Maha-Chohan

himself would be watching.

When Helena’s train pulled into Paris, she was greeted on the platform by Olcott, her old New York friend William Judge, and an embarrassed but obedient Mohini, who managed a stylish nosedive. At the age of thirty-two William Judge was finally burning his bridges. During the five-year radical separation from H.P.B. and Henry Olcott, Judge had continued to write plaintive letters to Olcott and then to Damodar, beefing that he was being left out and begging for crumbs of news about the Masters. Happiness had eluded him: he had few friends, a miserably unhappy relationship with his wife, and a seemingly small knack for earning a decent living, even though he had made several trips to Venezuela, where he had invested in a silver mine. In his letters to India, he constantly mentioned Ella Judge, whose antipathy toward the Theosophical Society had, if anything, grown with the years. He wanted desperately to leave her but, as she often reminded him, it was not fair for him “to run off leaving debts behind me unpaid and a woman unprovided for who through my solicitation left a good paying position as a teacher to marry me. She cannot recover it.” Feeling “truly in hell,”

11

he thought of himself as living “in a little private hot-house of my own construction,” in which he could see the world passing but “the fear of being cut prevents me running through the glass windows.”

12