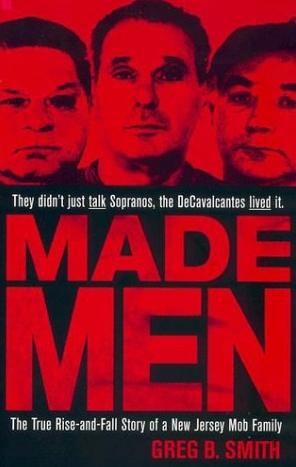

Made Men

Authors: Greg B. Smith

The True Rise-and-Fall Story of a New Jersey Mob Family

Greg B. Smith

b

BERKLEY BOOKS, NEW YORK

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are

used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

A BERKLEY Book / published by arrangement with the author

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2003 by Greg B. Smith

This book may not be reproduced in whole or part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. Making or distributing electronic copies of this book constitutes copyright infringement and could subject the infringer to criminal and civil liability.

For information address:

The Berkley Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

ISBN: 0-7865-3520-2

A BERKLEYBOOK®

BERKLEY Books first published by Berkley Publishing Group, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014. BERKLEY and the "B" design are trademarks belonging to Penguin Putnam Inc.

To Lizzy, Damon and Brendan

Acknowledgments

Much thanks is due to a number of people who supported my effort to get things right and readable. The list is long and incomplete, starting with prominent members of the New York criminal defense bar Gerald Shargel, Steve Kartagener, Francisco Celedonio, Joseph Tacopina and Gregory O’Connell. On the government side, thanks especially goes to assistant U.S. attorneys Lisa Korologos and John Hillebrecht and FBI special agent George Hanna. The story is not complete without FBI agents Eileen O’Rourke, Jay Kramer and Seamus McElearney, and, of course, New York City Police Department detective John DiCaprio. Also gratitude goes to Bob Buccino, former deputy chief of New Jersey’s Criminal Justice Division for a serious history lesson and to Marvin Smilon for remembering everything. I’d also like to thank my editor, Tom Colgan, and agent, Jane Dystel, for guiding me through the forest when I lost the trail.

August 9, 1994

On a hot August twilight in Queens, the taxpaying citizens are up in arms and out in force. Three hundred furious people crowd onto a sidewalk in a neighborhood of mom-and-pop businesses and middle-class apartment buildings called Rego Park. They yell and holler and generally make their First Amendment rights known. Because there are so many of them, they are jammed in behind blue NYPD barricades next to Ben’s Best Deli and Carpet City, a crowd of mild-mannered people wearing khaki shorts, T-shirts, and fanny packs who have gathered together to vent. A thunderstorm that rumbled through earlier is gone and the air is still thick with humidity. Occasionally inchoate shouting coalesces into a discernible chant.

They carry hand-scrawled cardboard signs such as

63RD DRIVE IS NOT 42ND ST

. and

XXX

=

NO NO NO

.

There are moms and dads and babies in strollers, elementary-school teachers, a city-council woman with a microphone and a podium. Cops working overtime look on, not bothering to disguise their amusement. The crowd is jeering and cheering and jabbing their fingers in the general direction of a storefront at 96-24 Queens Boulevard from which can be vaguely heard a throbbing

dunh-dunhdunh

of disco left over from the 1970s. Over the door of this smoked-glass storefront in lurid blue-and-red neon is one word that makes the neighbors nuts:

It is a strip club, and it has landed squarely in the middle of Archie Bunker’s Queens, right across the street from the old single-screen Trylon Movie Theater, around the corner from the Rego Park Jewish Center, and just up the block from Public School 139. This is the heart and soul of Queens, the borough of choice for millions of striving immigrants who come to this country of promise and McDonald’s to live a better life. They expect decent schools, safe streets, and convenient parking spots. They do not expect

ALL NUDE ALL THE TIME

, and that is why, since Wiggles opened on July 13, 1994, there have been protests on the street outside nearly every single night.

That is saying a lot for people who have to work for a living. They are making time in their busy days to stand outside Wiggles and holler. They are writing letters to their civic representatives. They are signing petitions and cobbling together a lobby. These neighbors, to put it mildly, despise this Wiggles. They loathe this Wiggles with the enmity of property owners who fear the value of their hold

ings will soon decline. They also fear for their children, as they are more than happy to repeat to the one reporter who shows up with a notepad from the Queens-based newspaper

Newsday.

“I raised my children here because of the good schools. This just isn’t that kind of neighborhood.” Ibn Art, a protester who’s lived in Rego Park for twenty-five years, fumes without specifying exactly what “that” kind of neighborhood might be. “I’m one hundred percent against this club.”

Marcia Lynn, who helped protest against another strip club down Queens Boulevard called Runway 69, puts forth a more dramatic scenario. She predicts that not only mere children but the children of dedicated religious families attending a nearby synagogue on Saturday evening will, inevitably, wander out of temple and be forced to confront Wiggles. There they will behold the photographs of headliners with interesting-sounding names like Erica Everest, Niki Knockers, and Crystal Knight.

“We need to close down all these places,” she warns. “The wrong people are coming in.” There is a blue wooden stage erected on the sidewalk upon which the politicians are holding forth. One of them is City Councilwoman Karen Koslowitz, who has already won votes campaigning against Runway 69 a few blocks away. Koslowitz has come to realize that standing up to strip clubs is an extremely popular stance for an ambitious politician. She has helped organize this protest, and she now stands onstage hammering away. She is a grandmotherly figure who could easily be mistaken for a Barbra Streisand fan. She has a tendency to wear tinted glasses, carry leopard-pattern handbags, and say things like “For this they have the First Amendment?”

“Children pass through here constantly!” she tells the crowd. “This is a family community!”

The crowd cheers like wrestling fans, stirred by the need to kick this trash out of the neighborhood. They are so organized, they even have their own ribbons—red, white, and blue affairs that are worn on lapels, signifying that the right to protest against the local strip joint is as American as credit cards. Suddenly the crowd notices some customers who are headed into the club. One of the activists, a middle-aged man with a receding hairline, whips out a cheap camera and begins taking photographs. One of the customers, a man wearing a black, orange, and blue Knicks warm-up suit smiles and mugs for the camera. He says the girls inside aren’t worth the admission price. Another man is not so amused at having his picture taken. He pulls his turquoise windbreaker over his head like a cliché gangster. He offers up an interesting gesture involving a single finger and disappears inside the club.

The crowd spots two strippers strutting down the sidewalk on spike heels, headed for the door. Both have somehow jammed themselves into absurdly tight blue jeans that defy all the laws of physics. The blonde sneers at the amateur photographer, but the brunette, who wears a blackgauze blouse with black bra clearly visible underneath, suddenly wheels around with her own camera and begins taking pictures of the picture taker.

“Why don’t you just leave us alone?” she whines as she heads into the club. “We’re just trying to make a living.”

Inside the club, all forms of civil protest are obliterated by the thundering disco beat. In the main room three completely naked women—they would call themselves “entertainers”—gyrate to the beat on a stage that is raised two feet off the floor. Their bodies are reflected in the mirrors on all the walls and the ceiling above. There is a “Champagne Room” in the back—a small room filled with tiny booths for “private” dances. There is a poolroom and a TV room and a number of other miscellaneous “lounges” located throughout the club’s three thousand square feet of space.

Though the neighborhood protest outside cannot be heard above the din, its effects are obvious.

A sign at the entrance that wasn’t there before the protests states:

Don’t let anyone take away your individual rights. Celebrate your freedom of choice on us: FREE Admission

FREE Buffet

FREE Entertainment

Wiggles has taken to mentioning—in newspaper advertisements placed in the sports sections of the local tabloids right next to the fishing column and underneath the daily football line—the presence of an ATM “available on the premises” as well as valet parking for the commuter set. On this night of grand protest, there appears to be more strippers than customers, which gives the place a lonely feel. A handful of “entertainers” do their jobs while gazing off into mirrors. A small group of men sip colas and club sodas and stare up in slack-jawed aesthetic appreciation of the dedication these girls show to their craft. Like most strip clubs, the place reeks of cigarette smoke. Unlike most strip clubs, the place does not reek of alcohol.

That’s because there is none. Wiggles is booze-free, opened by people sophisticated enough to know that if you serve liquor, you have to abide by a phone-book-size list of

rules and regulations that apply under New York State liquor laws. One of the laws says that if you serve booze, the strippers can’t take all their clothing off—just their tops. And though Wiggles claims to be a topless club, the strippers often expand the interpretation of the term

topless

by removing their panties. Alcohol, therefore, is replaced by “juice.” Wiggles is, in fact, listed in the Yellow Pages as a “topless juice bar.” The club’s “manager,” Karen English, identifies herself as a “retired” topless dancer who has been in “the business” forever, and she is mightily offended at the slander and invective that is flying around on the sidewalk outside.

“I feel that everyone has a right to their opinion, but I have an excellent reputation in this business,” she says, making the point twice that she runs a topless club, not a nude bar: “We are not a nude bar. That is a misconception. We will serve no alcohol.”

She actually says, “I run a clean establishment.” But the ex-stripper named English speaks not from a position of ownership, and that is because the true owner of Wiggles is a man who prefers to stay away from the cameras and out of the headlines that have exploded around his club. In fact, his name is not on any document associated with the club. According to all forms of public documentation available to the average investigative reporter, Wiggles is actually controlled by a shell corporation with the ridiculous name of Din Din Seafood, Inc. And Din Din Seafood lists no president, treasurer, or secretary. Its “chairman of the board” is listed as Paul Ranieri, who sometimes says he is the owner of the club, and sometimes says he is the manager. But behind the scenes there is another man who calls the shots. His name is Vincent Palermo, and he is a capo known as Vinny Ocean in the littlest Mafia family in North America—the DeCavalcante crime family of New Jersey.

On this hot August night, with three hundred fuming citizens beating the drum of civil protest outside his club, Vinny Ocean is nowhere to be found.

Keeping Wiggles alive is extremely important to Vinny Ocean for a simple reason: Wiggles is a money machine. It generates hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash each week—little, crumpled-up, sweaty fives and tens and twenties that drunken patrons jam in the G-strings of the “entertainers.” There are piles of dollars to be made, all handed over by leering businessmen who wind up in the Champagne Room for a personal “lap dance.” They plunk down ten bucks for a can of soda and do not care because it will all reimbursed by their employers as a “business expense.”

Vinny rarely stops by the club. Instead he sends his right-hand man, Joey O Masella, to pick up the weekly take. Because so many of the transactions take place in cash, Joey O often ends up carting around big fat envelopes. Much of this money is kept in a secret safe in the strip club’s main office, which only a handful of employees know about. Joey O spends so much time coming and going from Wiggles, he has taken to complaining that he could hurt his back, which is not so good these days, carrying around this much cash. In short, Wiggles is good business for Vinny Ocean. The cash comes in, Vinny is happy, the DeCavalcante crime family is happy. God forbid a bunch of noisy puritans with protest signs should ruin all that.

Many of the noisy puritans, in fact, have long suspected that the club is controlled by the mob. They see these guys hanging around, and some of the protesters will swear they’ve been followed home after a tough night of protest. But Vinny Ocean knows it’s best to keep an extremely low profile in these matters, because he realizes that the future of Wiggles is far from certain. There is a new mayor down at City Hall named Rudy Giuliani, a former federal prosecutor who’s taken on what he has deemed the pathetic “quality of life” in New York City. This Giuliani has announced a holy jihad against squeegee men and homeless people, so it is not too difficult to imagine a new campaign to shut down the strip clubs as well. In fact, just such a movement is afoot. Giuliani has put his considerable political weight behind a bill that would banish strip clubs like Wiggles from residential areas and require that they be located more than five hundred feet away from churches and schools and day-care centers. The bill has been languishing in a city council committee, but the mayor brought it back from the dead. If it passes, Wiggles could be forced to move out of the middle-class confines of Rego Park and into the kind of economic Siberia one finds in scary industrialized zones down near the waterfront or out near airports. Not the kind of places that Vinny Ocean, entrepreneur, sees as the future for exotic dancing in New York.

If anything can be said about Vinny Ocean, it is that he is a dedicated entrepreneur. “I love work,” Vinny Ocean tells people. “I worked my whole life. Eleven, twelve years old. Two jobs. My whole life, I love to work. People see that you have a nice house, a nice car, they figure maybe you did something wrong. My whole life, never,

never

did I do one thing wrong. That I know of.”

Vinny Ocean looks and thinks like a smart businessman. He is a short, compact man who resembles the actor Robert Wagner, with a distinguished patch of silver at the temples, a healthy head of brown hair on top, and a deep tan. He is forty-eight years old and is working on his second marriage. He has pulled himself out of debt and is now headed fast toward making his first million.

For years, he struggled financially. For years he ran a successful wholesale fish business in the Fulton Fish Market down in lower Manhattan, where he earned the nickname, Vinny Ocean, but not a whole lot else. In the mid-1980s, he owed everybody—the local hospital, local doctors, the federal government. The tax liens against his property (actually, everything was in his second wife’s name) totaled $68,000. He was paying a hefty mortgage on a nice mansion on the Long Island waterfront—eight rooms, two bathrooms, one fireplace, a big pier, tucked away in an isolated section of suburban Island Park, Long Island (held under a corporate shell called Fishing Well, Inc.). He had two social security numbers and paid alimony to his first wife, with whom he had two children. He was supporting a new, second family, complete with two teenage girls and eight-year-old Vinny Jr. He was sending all three to Catholic school, with college on the horizon. He’d already put his first son, Michael, through Adelphi Academy High School in Brooklyn and then Fordham University in the Bronx. His first daughter, Renee, also attended college on his tab.

The cost of being a family guy was dear but predictable. He’d come out of a family of eight children (five girls, three boys) and was raised old-school Catholic in postwar Brooklyn. His father came to America from Italy when he was a teenager. His life was like a scene from

Once Upon a Time in America.

“Ours is a very close-knit family,” his sister Claire wrote in a letter to a judge. “We were raised in a strict Catholic household. My father who immigrated here when he was in his teens, emphasized love for one another, our fellow man, for our country and high moral standards.” Vinny was an altar boy.

When the former altar boy was just sixteen years old, his father died. He had to leave school and went to work at “two jobs to help support my mother and the younger children,” his sister Claire wrote. Another sister, Nancy, remembers Vinny more or less supported the family after her father died because their mother was a bedridden asthmatic. Just about everybody who has a story to tell about Vinny Ocean would mention his devotion to family. His daughter Tara says she once saw him stop a man from beating his son. During a family barbecue, Vinny was the guy who jumped in the pool and rescued the toddler who’d accidentally fallen in.

A casual examination of Vinny’s world reveals the basic résumé of the hardworking suburban dad. He and his family attended Sacred Heart Church in Island Park every Sunday. Father John Tutone knew him by his first name. Vinny Ocean watched

Annie

a thousand times with his daughter Danielle. He drove the girls to Brownies’ meetings. He once took in a troubled teenager named Richie, became his godfather, and let him stay in his home every weekend for a year while Richie studied the Catholic sacraments and prepared to be baptized and to receive first Communion and confirmation.

And, of course, he was a made guy.

In the early 1960s, he met and married the niece of Simone Rizzo DeCavalcante, who would soon be known to the world as Sam the Plumber. Sam the Mafia boss took a liking to his niece’s new young man and began inviting him by the social club in Kenilworth, New Jersey. Vinny was working at the fish markets in the early morning hours and hanging out with the wiseguys on Sunday afternoons at the social club or at Sam’s table at Angie and Min’s restaurant in Kenilworth. He was seen as an earner. In 1965, when he was just twenty years old, he became a made member of Sam the Plumber’s crime family.

Never again would he be just another guy from the fish market.

Now he was

amico nos

—a friend of ours. He was part of a much larger organization that included five crime families in New York City and one in New Jersey. All six had their moments of fame over the years that became gilded and polished and placed squarely in the gauzy mythology of gangster-dom. At the time that Vinny Ocean became

amico nos,

the DeCavalcante family was a small but respected organization. It had a virtual lock on most of the unions that did construction work in northern New Jersey and a good relationship with the five New York families who ran the gangster world. Small but respected. And Vinny Ocean was a part of all that.

Nearly thirty years later, the mob wasn’t what it used to be.

In Vinny’s family, the FBI had successfully planted a bug in Sam the Plumber’s office and captured nearly two years of conversations. Sam the Plumber was convicted and ultimately retired. The New York families were in even more of a mess. The Colombo family had lost itself in two terrible, bloody wars in the streets of Brooklyn. Its members were being prosecuted one by one. The Luchese family had gone underground ever since one of its middle managers decided it would be a good idea to violate mob “rules” and try to shoot the sister of an informant. The Bonanno clan, the smallest of the New York five, was a shell of its former self after being kicked out of the mob’s famous ruling body, the Commission. The boss of the Genovese family, Vincent (the Chin) Gigante, had taken to wandering through the streets of Greenwich Village in a bathrobe, unshaven and muttering to himself about Jesus. Subpoenas were everywhere. When he was indicted, his own lawyers said he was insane.

As of 1994, the most powerful family in America—the Gambino family—was on the ropes, brought down by its boss, John Gotti, the Dapper Don, a man whose mountainous ego was surpassed only by his inability to keep his mouth shut. The high-living Gotti dodged not one but three prosecutions (mostly by fixing juries), ate at fine Manhattan restaurants, danced till dawn, and offered a raffish Al Capone smirk to reporters who dogged his every move. By 1992, he was finished, convicted of murder and racketeering and just about every Cosa Nostra sin imaginable. He now sat in a maximum-security prison, fuming about all the rats who’d turned on him, unaware that his own words, captured by FBI bugs, were the true reason for his downfall.

Different theories emerged about the downfall of the mob. Some believed it was simply an extraordinary effort by law enforcement. Some said it was sloppy behavior by a secret society that was no longer so secret. A few saw something else—a group of criminals done in by their own mythology.

With Gotti, there was practically a cottage industry between the movies and books and talk-show discussions. His image as a boastful, well-dressed hoodlum catered to the notion that the mob was a glamorous American institution. Gotti was seen in some circles as an antihero, a guy who thumbed his nose at law enforcement while impressing the working people with old-fashioned fireworks displays every Fourth of July in his Queens neighborhood. Even Gotti believed it. He talked about “my public” as if he were George Raft or Paul Muni or Robert De Niro. Here was the myth of the crime boss as Robin Hood. Here was

The Godfather

of Mario Puzo, who had somehow managed to create the Men of Honor fiction.

In 1994, the Gambino crime family had become material for popular culture. If Jay Leno or David Letterman needed a Mafia joke, inevitably they would mention the Gambino crime family. Gotti had made the cover of

Time

as the face of organized crime in America. When people made jokes about “sleeping with the fishes” and “make him an offer he can’t refuse,” they thought of Gotti and the Gambino crime family, even though its power and strength had been considerably weakened by Gotti’s conviction two years earlier.

When people thought of the Mafia in 1994, they most certainly did not think of the DeCavalcante crime family— New Jersey’s only homegrown Mafia clan. By the time the protesters took to marching outside Vinny Palermo’s strip club in Queens, the DeCavalcante crime family had fallen into a near-permanent stupor. Within seven years, the family’s underboss had been murdered, the boss had been jailed, and the man who’d been appointed to replace him as acting boss on the street had been murdered by his own men. The guy left in charge, Giaciano (Jake) Amari, had cancer and was slowly dying. Most of the leadership of the family consisted of extremely old men stuck in the old ways. There was one exception in the DeCavalcante crime family in 1994—an up-and-coming capo named Vinny Ocean.