Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy (16 page)

Read Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy Online

Authors: Robert Sallares

Tags: #ISBN-13: 9780199248506, #Oxford University Press, #USA, #History

Ecology of malaria

73

12. The coastal forest of the Parco Naturale della Maremma, in the direction of the Ombrone river valley, and the Canale Scoglietto Collelungo.

In the past the water in such drainage canals often flowed too slowly to prevent mosquitoes breeding in them. The pine forest (principally

Pinus pinea

) on the left was planted in the nineteenth century. The Monti dell’

Uccellina (to the right and behind the line of sight) are covered by oak forests.

the summer was assisted by hot, dry south winds, which were associated with malaria by Theophrastus and other ancient authors.⁷⁴

In the fifth century Empedocles is said to have blocked up a mountain gorge in order to prevent a pestilential south wind from bringing problems in pregnancy to women (placental malaria) and disease on to the plain surrounding his own city of Akragas in Sicily.⁷⁵ Horace also mentioned the pestilential south wind in his odes.⁷⁶ Similar ideas recurred throughout later history. The doctor Perinto Collodi at Bibbona gave a detailed description of the ⁷⁴ Theophrastus,

de ventibus

57, ed. Coutant and Eichenlaub (1975): ka≥ p3lin xhro≥ ka≥ m¶

Ëdat*deiß Ônteß oÈ nÎtoi puret*deiß.

⁷⁵ Plutarch,

Moralia

515c: Ø d† fusikÏß ∞Empedokl[ß Ôrouß tin¤ diasf3ga barŸn ka≥

nos*dh kat¤ t0n ped≤wn tÏn nÎton ƒmpnvousan ƒmfr3xaß, loimÏn πdoxen ƒkkle∏sai t[ß c*raß (It was thought that the natural philospher Empedocles shut pestilence out of his country by blocking a gorge, which allowed an oppressive and unhealthy south wind to blow on to the plains.). See also Plutarch,

Moralia

1126b and the other sources cited by Diels-Kranz 31 A1, A2, A14.

⁷⁶ Horace,

Carmina

23.1–8.

74

Ecology of malaria

association of the sirocco wind with disease among seasonal migrant workers returning from the Tuscan Maremma to Liguria in 1614. Domenico Panarolo (1587–1657) described the austral wind as a ‘deadly enemy of health’. Elsewhere in his works on winds and airs he noted the idea prevalent in Rome at the time that the sirocco wind brought ‘bad air’ to Rome from the Pontine Marshes. Not everyone accepted such ideas. The anonymous author of a tract on mal’aria written in the late eighteenth century perceptively argued that ‘bad air’ was generated regardless of which wind was blowing and that in fact it was most abundant if there was no wind at all (mosquitoes don’t like strong winds). Baccelli maintained that the sirocco wind was unhealthy in Rome in the nineteenth century, particularly if it was humid.⁷⁷ However, a very long period of continuous dry heat during the summer tended to reduce the frequency of cases of malaria, since the mosquitoes eventually began to run out of breeding sites. Consequently the frequency of malaria increased after occasional summer showers, and particularly after the first autumn rains.⁷⁸ This combination of circumstances again illustrates the complexity of the phenomena in question.

Anopheles

larvae generally prefer stagnant water. Lancisi noted that running waters were healthy.⁷⁹ Nevertheless they can also thrive in water that is moving very slowly.

A. labranchiae

and

A.

sacharovi

are happy to breed in ditches or canals so long as the water is not moving faster than about two kilometres per hour. Consequently the construction of canals to drain marshes frequently made the situation with regard to malaria worse rather than better in central Italy in the past. This happened, for example, during the project to reclaim the Tiber delta region around Ostia in 1885–9, since the new drainage channels proved to be even better breeding habitats for

Anopheles

mosquitoes than the marshes that they drained. Around Ostia

Anopheles

larvae were found in most of the drainage canals, which were stagnant and overgrown with aquatic vegetation, by the time of Sambon’s field observations in the ⁷⁷ For south winds as ‘bringers of fever’ (puret*deiß) see also [Aristotle,]

Problems 1.23.862a, Pliny,

NH

2.48.127, Celsus,

de medicina

1.10.4 and 2.1.3–4; Sidonius Apollinaris 1.5.8

associated the Atabulus wind from Calabria with malaria; Doni (1667: 79–84); Lancisi (1717: 49); Cipolla (1992: 52) on Bibbona; Panarolo (1642

a

) and (1642

b

):

inimico mortale della salubrità

; Lapi (1749: 64–5); Anon. (1793: 24); Baccelli (1881: 161–3); North (1896: 138).

⁷⁸ Hirsch (1883: 258) noted that an epidemic started in Rome in October 1795 after the first autumn rains, following a long dry summer.

⁷⁹ Lancisi (1717: 30–2).

Ecology of malaria

75

summer of 1900.⁸⁰ This is likely to be one reason why the reported drainage of the Pontine Marshes in 160 by Cornelius Cethegus failed to make any impact on malaria and probably even intensified it, since malaria was certainly endemic in this region in the Late Republic, as will be seen in Chapter 6 below. The gradient of the land in the Pontine Marshes was too low for canals to carry water away rapidly. Drainage is a complicated business. Many, perhaps even most, drainage schemes in antiquity were probably failures.

There are numerous examples of early modern drainage schemes that were spectacular failures with regard to malaria, besides the Ostia project already mentioned. Doni noted that the bonifications (the reclamation by drainage of marshlands) of Pope Sixtus V

(1585–90) did not make the Pontine region any healthier. Sixtus V

was brave enough or foolish enough to visit his own bonifications while they were in progress, and his death was attributed by some contemporary authors to tertian fever contracted during his visit.⁸¹

There is some detailed information available for the demography of the human population of the Pontine Marshes at the time of the last major attempt at drainage before Mussolini finally succeeded, namely the attempt by Pope Pius VI in the late eighteenth century.

These records show that mortality significantly

increased

following the drainage operations.⁸² Almost certainly the operations in 160

produced the same result. Even the reassessments by Traina and Leveau of ancient attitudes towards marshes, which attempt to put them in the most favourable light possible (and in doing so fail to comprehend that many Mediterranean wetlands were rendered almost uninhabitable by malaria in the past), are forced in the end to admit that drainage schemes in antiquity produced limited results.⁸³ Herlihy, discussing the problems of Pisa in the face of malaria during the Renaissance, observed acutely that ‘of course the expenditure of much wealth and energy upon public works does not prove that conditions are salubrious but only that the ⁸⁰ Hackett (1937: 18); Sambon (1901

a

: 198).

⁸¹ Doni (1667: 139–40); Nicolai (1800: 138).

⁸² Corti (1989) for modern demographic research; Nicolai (1800: bks iii and iv) gave a contemporary view of Pius’ bonifications.

⁸³ Hackett (1937: 17). Traina (1986: 712) concluded that:

tutte le opere di sistemazione idraulica anteriori al XVII secolo, in Occidente, sono delle migliorie più che delle bonifiche vere e proprie; in ogni caso, il mondo antico conosceva la bonifica idraulica, non quella integrale

. Leveau (1993: 16) affirmed that ‘

en fait l’Antiquité n’a pas connu le drainage total au sens où nous l’envisageons. Les véritables assèchements ont commencé au XVIIIe siècle et il serait faux de croire que les terres conquises aient été le plus souvent drainées à l’époque romaine puis reconquises par le marais au Moyen Age

’.

76

Ecology of malaria

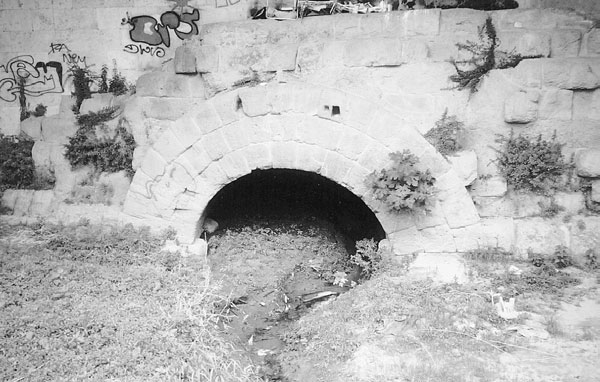

13. The entrance (near Ponte Palatino) to the Cloaca Maxima, ancient Rome’s biggest sewer, complete with modern graffiti. Ancient Rome had drainage problems from the beginning of its history.

problem is great’.⁸⁴ Lake Velinus, first drained by M. Curius Dentatus in the early third century , was a typical example of the results of drainage in antiquity. Varro commented on how rapidly grass grew on the drained plain. As a result it was famous for animal husbandry, especially horse breeding, but Cicero stated that the drainage of the plain left the soil moist. That is not surprising if it could sustain rapid plant growth. This type of drainage would not have defeated the mosquito vectors of malaria, and might have even favoured them.⁸⁵

In antiquity networks of cuniculi (underground tunnels connected by vertical shafts to the surface) were constructed in various parts of Etruria and Latium. The character of these waterworks resembles the famous Cloaca Maxima, which was originally constructed to turn a stream running through the Roman Forum into a canal. Pliny the Elder described the large investment of labour ⁸⁴ Herlihy (1958: 47).

⁸⁵ Cicero,

Letters to Atticus

90.5, ed. Shackleton-Bailey (1965–70):

Lacus Velinus a M. Curio emissus interciso monte in Nar

〈

em

〉

defluit; ex quo est illa siccata et umida tamen modice Rosea

. Pratesi and Tassi (1977: 98–103) described the modern environment of the Lake Velinus region; Varro, RR

1.7.10.

Ecology of malaria

77

required for the construction of the sewers of Rome, which he attributed to Tarquinius Priscus.⁸⁶ Both the purpose(s) and date(s) of the cuniculi have been hotly debated. This type of hydraulic technology was widely distributed in central Italy. The view has been expressed that the Etruscans devised it and passed it on to the Latins, although other historians have suggested that it is a mistake to assume Etruscan influence lies behind everything that the Latins did. The largest of the cuniculi, namely the emissaries for the Lago di Nemi and the Lago di Albano, might have had some religious significance, in view, for example, of the tale told by ancient authors of the prophecy that the Romans would not capture Veii until they had drained the Alban Lake.⁸⁷ Some cuniculi are connected to Etruscan roads, although others are linked to Roman villas, while a few are definitely post-classical, but in most cases dating criteria are elusive. In fact, different scholars have placed them in every century from

c

.800 to

c

.400 . Ampolo expressed the view that the cuniculi of Veii, which have received the most intense scrutiny, were mainly built in the fifth and fourth centuries , either side of the Roman conquest of Veii, for drainage purposes.

Veii itself was apparently healthy then (see Ch. 3 above), but that does not necessarily have anything to do with the cuniculi. Ampolo also observed that drainage was particularly important for olive cultivation in Latium in antiquity. Quilici Gigli concluded that the cuniculi of the Velletri region, immediately north of the Pontine Marshes, were more sophisticated than those around Veii and were constructed during the period of intense Roman activity in the Pontine region in the fourth century (see Ch. 6 below). This is the most plausible solution to the problem, but there are other hypotheses. Attema reckoned that the cuniculi of Velletri were created in the sixth century to facilitate arable farming. He also discussed Blanchère’s ideas.⁸⁸

In the nineteenth century de la Blanchère had raised the question of whether the cuniculi played a role in the history of malaria ⁸⁶ Pliny,

NH

36.24.104–8 on the sewers of Rome; in

NH

, 3.16.120 he attributed a canal in the Po delta to the Etruscans.

⁸⁷ Livy 5.15.2–16.1, 16.8–11, and Dionysius Hal.

AR

12.10–13 on the emissary from the Alban Lake.

⁸⁸ Blanchère (1882

a

) and (1882

b

); Tommasi-Crudeli (1881

a

) and (1882); Celli (1933: 12–16, 19–20); Ampolo (1980: 36–8); Potter (1979: 84–7) and (1981: 9–11); Quilici (1979: 322); Nicolet (1988: 57); Attema (1993: 65–76); Thomas and Wilson (1994: 143). Cornell (1995: 164–5) argued that the cuniculi cannot be dated; Quilici Gigli (1997: 194–8).

78

Ecology of malaria

in central Italy in antiquity. However, their geographical distribution was not correlated with the distribution of malaria, which reached its greatest intensity along the coast, but with a particular geology. This can readily be seen by comparing Judson and Kahane’s map of the distribution of the cuniculi with the map of the distribution of malaria in Latium in 1782 given by Bonelli.

Judson and Kahane argued that most of the cuniculi are associated with a particular type of impermeable soil, namely the brown Mediterranean soil of the mesophytic forest. This pedological formation is most abundant in the southern and western slopes of the Alban Hills and around Veii, overlying volcanic

tufo

. Consequently Angelo Celli and more recently Franco Ravelli were probably right to argue that the cuniculi were mainly built before the spread of malaria in western central Italy and were not intended as a defence against malaria. The cuniculi were not designed to eliminate malaria, and certainly did not have that effect either in antiquity or more recently. In some cases they might conceivably have even facilitated the spread of malaria, if they were built before that happened, as the commonest view among historians maintains. If the connection with malaria is discarded, various possibilities for the function(s) of the cuniculi remain. Judson and Kahane suggested that most of the cuniculi were intended to improve certain types of badly drained land for agricultural purposes. This has been a popular opinion. However, Franco Ravelli, an expert on irrigation systems, has argued that the cuniculi were intended principally to capture and purify water for drinking purposes. He observed that they are mostly dry today and suggested that they were constructed in a period in the middle of the first millennium when there was more rainfall than there is today (see Ch. 4. 5 below).⁸⁹