Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy (41 page)

Read Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy Online

Authors: Robert Sallares

Tags: #ISBN-13: 9780199248506, #Oxford University Press, #USA, #History

He singled out the areas of the Campus Martius, between the Aventine and the Palatine hills, and the area between the Tiber and the Aventine as particularly dangerous (although the summit of the Aventine hill itself was healthy), as well as the area of the Ostian Gate, although the Leonine region was the worst of all.

Doni had no difficulty recognizing the continuous and semitertian fevers described by Asclepiades and Galen (quoted below) as the cause of the problems in his own time.¹⁸ The view expressed by Doni, Donatus, and later writers such as Lancisi, de Tournon, Colin, and North that a dense human population reduces the frequency of malaria is an instance of a correlation that does not necessarily indicate causation.¹⁹ Of relevance here is the standard view in statistics that the fact that two sets of data are correlated does not prove that one of them is causing the other.

Since most people in the early modern period chose, if possible, to live in relatively healthy areas, most areas of dense habitation ¹⁷ Doni (1667: 8–9):

Quaecunque loca crebris aedificiis ambiuntur, atque editiora sunt, et in Septentrio-nem, atque Orientem spectant, et longius a Tiberi absunt, salubriora: vice versa quae seiuncta sunt, et remota a frequentioribus tectis, situque sunt humili, ac maxime in convallibus; tum propiora Tiberi, in Meridiem, atque Occasum solis spectantia, minus salubria a peritioribus habentur

.

¹⁸ Doni (1667: 6). Doni’s work was partly written in response to the sixteenth century book of Alessandro Petronio (translated into Italian by Paravicini (1592) ), a doctor from Cività Castellana who worked in Rome. He acknowledged that quotidian fevers and lethargy were common in Rome (

si vedano spesso

—Paravicini (1592: 200) ), although he thought that semitertian fevers were rare, but nevertheless suggested that fevers as a whole were much less frequent in Rome than the ailments upon which he wished to concentrate, namely excess of humours in the head (

capiplenio

) and indigestion! He wished to concentrate on ailments which could possibly be influenced by his focus on diet, lifestyle, and exercise. Of course headache and indigestion are much commoner than major infectious diseases in all human populations, but the fact remains that only major infectious diseases have significant demographic consequences!

¹⁹

e.g.

Donatus (1694: bk iii. ch. 21, pp. 273–4):

Quaedam alia de Vaticano memorantur, haud sane firmis auctoritatibus nixa, praeter frequentia in eo campo sepulchra, et insalubre Coelum, quod noster aetas propter Civium, tectorumque frequentiam salubrius experitur

.

210

City of Rome

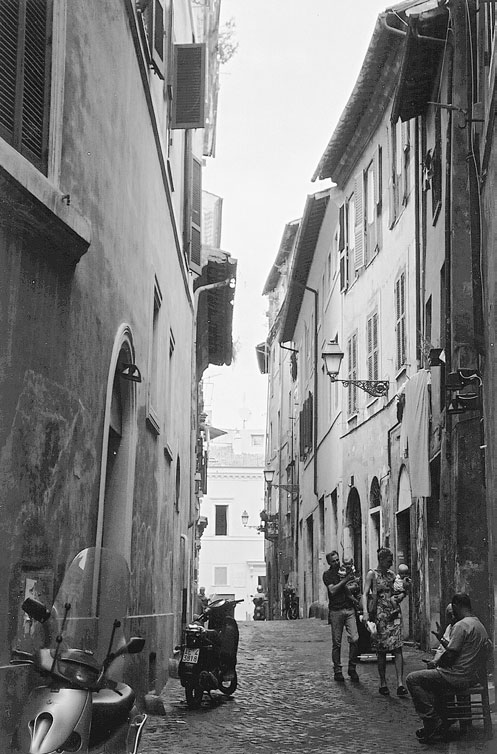

30. Via della Reginella, connecting Via del Portico d’Ottavio to Piazza Mattei, is a relic of the old Jewish Ghetto in Rome, a district that was walled until 1848. Despite its location, close to the River Tiber, and the poor living standards of its inhabitants, there was little or no malaria there.

This may be attributed to the densely packed houses, with no gardens between them, and so a lack of mosquito breeding sites.

City of Rome

211

were fairly healthy. However, that does not prove that a high human population density by itself is enough to defeat malaria, and the comments of the ancient medical writers (to be discussed shortly) indicate that that was not the case in ancient Rome. The classic example given in early modern discussions of malaria in Rome was the Jewish ghetto. This district remained walled until 1848. It had a high population density and was free of malaria even though it was situated close to the Tiber, in the vicinity of Isola Tiberina. The key to understanding the situation in the ghetto is not the human population density as such, or the height of the buildings in it, but the absence of gardens in between the buildings. Irrigated gardens where Romans grew vegetables during the heat of the Mediterranean summer made a significant contribution to feeding the population of the city. However, they also furnished ideal breeding sites for mosquitoes, and this was explicitly noted in both ancient and early modern literary sources. For example, the anonymous author of a discourse on

mal’aria

written near the end of the eighteenth century observed that gardens were one of the deadliest producers of ‘bad air’ and noted the abundance of mosquitoes in gardens.²⁰ Similarly in antiquity Pliny the Elder noted the abundance of mosquitoes (

culices

) in well-watered gardens and recommended measures to try to drive them away.²¹ This is a crucial piece of evidence because it identifies irrigated gardens, particularly those in which trees or bushes provided resting and hiding places for mosquitoes, as important breeding sites for mosquitoes in and around the city of Rome.²² The elimination of gardens from many parts of Rome during the development of the modern city, as it changed in the direction of the modern situation in which most people live in blocks of flats without gardens, was an important factor in the eradication of malaria from Rome.

The observations of the early modern authors as a whole prove the importance of malaria not necessarily as a regular direct agent of mortality (although there certainly were some major epidemics from time to time), but as a determinant of settlement patterns ²⁰ Anon. (1793: 56):

zanzare, e tutti gli animali indicatori e propagatori della corruzione

. Tommasi-Crudeli (1892: 127) discussed the connection between malaria and market gardening in Rome.

²¹ Pliny,

NH

19.58.180:

infestant et culices riguos hortos, praecipue si sint arbusculae aliquae; hi galbano accenso fugantur

(Mosquitoes also infest irrigated gardens, especially if there are some shrubs; they are driven away by burning the resin of galbanum.).

²² Pliny,

NH

36.24.123 noted the abundant supplies of water to gardens in Rome.

212

City of Rome

in the city of Rome (at a time when the urban population was much smaller than during the Roman Empire). For example Gian Girolamo Lapi argued in the eighteenth century that intermittent fevers were no more frequent in Rome than in many other Italian cities and that it was safe to visit Rome in summer, even though he acknowledged that the air of the Roman Campagna was very unhealthy. However, even Lapi admitted that a majority of the citizens of Rome (

la maggiore parte

) were afraid of ‘bad air’, being unwilling to sleep in the villas in and around the city or even to move from one district of the city to another.²³ Malaria forced people to congregate in the healthier districts of the city, at a time when the unoccupied sections of the city amounted to about two thirds of the area within the Aurelian walls. Ellis Cornelia Knight mentioned a law in early modern Rome banning landlords from expelling tenants during the summer, so that no one should be forced to end up living in the dangerous parts of the city in summer.

Her words clearly show malaria acting as a determinant of settlement patterns even though she believed, like Lapi, that those parts of the city where people congregated were safe.

Seldom any rain falls during the months of July and August, and the air is perfectly calm . . . mephitic exhalations abound at this season of the year in the neighbourhood of any stagnant waters, and in the unfrequented parts of Rome, particularly over the catacombs. The few inhabitants who remain there are subject to fevers and agues, but their number is very inconsiderable; and no danger is to be apprehended where fires are kept up by any considerable number of houses. For this reason the cottagers of the Campagna usually leave their dwellings during summer, and sleep, either at Rome under the porticoes of the palaces and public edifices, or in the towns nearest to their little possessions. If they persist in remaining too long they get agues; and the greatest number of patients in the Roman hospitals, for the months of July, August, and September, consists of peasants from the circumiacent fields . . . During this month [sc. September], and the two preceding it, noone can be compelled to change his dwelling; as there is a law to that effect, for the purpose of preventing the pernicious consequences supposed to ensue, from the necessity of leaving a well-inhabited part of the town for one less salubrious.²⁴

Many later authors followed Doni’s approach to medical geography. Léon Colin produced a map of the frequency of malaria among the French troops stationed in various quarters of Rome in ²³ Lapi (1749: 11–16).

²⁴ Knight (1805: 4).

City of Rome

213

31. The Colosseum lay in a valley between the Esquiline, Palatine, and Caelian hills in Rome. Such lowlying localities were favourable to malaria in the past.

1864.²⁵ Celli cited the work of the doctor Maggiorani, who as recently as 1870 ‘considered not only the valleys of Rome, such as the Forum, the Colosseum, the Prati di Castello and the villa Borghese, to be centres from which arose pestiferous exhalations, but also declared that the populated hills of Rome were not immune from fever’. Celli also drew attention to a map of malaria in Rome in 1884 produced by two doctors, Lanzi and Torrigiani, who listed ‘even the quarters of Trastevere, Pincio, Viminale, Esquilin, Celio, Testaccio, Palatine’ as malarious.²⁶ This all too brief survey of literature on the medical geography of the city of ²⁵ A. Gabelli,

Prefazione

in

Monografia

(1881: l–li); North (1896: 238–42); Colin (1870: 88–9); Marchiafava and Bignami (1894: 23–7) on Colin’s classification of the malarial fevers which he observed in Rome. Beauchamp (1988: 258) made the observation that malaria is spreading today in developing countries which are experiencing rapid urbanization.

²⁶ Celli (1933: 167); Pinto (1882: 19–24) also described the healthy and unhealthy parts of Rome.

214

City of Rome

Rome proves that numerous parts of the city were affected by malaria in the fairly recent past. If we return to reconsider the already quoted text of Cicero,

de republica

, on the healthy location of Rome, it becomes evident that Cicero, in spite of his attack on Rullus for wanting to settle army veterans in the pestilential territory of Salpi in Apulia (see Ch. 10 below), was really no more interested in the health of the masses than he was in any other aspects of their wel-fare. When he described Rome as healthy, he was only thinking of the hilltop districts where the aristocracy lived, and ignored the lowlying areas where many poor Romans lived and worked.²⁷

This conclusion, at least, should not surprise historians with more conventional interests in political history.

To evaluate Cicero’s statement, it also must be remembered that owing to sediment deposition in the intervening valleys by Tiber floods and deliberate infills in both antiquity and modern times, the hills of Rome were more impressive as hills in the early stages of Roman history than they are today.²⁸ The Esquiline, the highest of the seven hills of Rome, is only 65 metres above sea level, although the Janiculum (usually not counted among the seven hills) reaches 82 metres above sea level. Baccelli categorized the unhealthy lowland areas as having a topsoil which was always damp, though not actually waterlogged, with evaporation from the surface, overlying a stratum of impermeable

cappellaccio

, with substantial run-off of water from the hills of Rome, in other words a geology resembling that in areas of the Campagna Romana where cuniculi were constructed in antiquity.²⁹ In the early eighteenth century Lancisi had already noticed a correlation between certain types of soil and unhealthy locations. Scobie pointed out that the streets of ancient Rome were wet owing to the overflow from fountains and public water basins. This probably also created breeding sites for mosquitoes right inside the city. Moreover it is easy to underestimate the number of lakes inside the city. The lake which Nero constructed for his Golden House (

Domus Aurea

) should not be allowed to dis-tract attention from all the other numerous bodies of water within the limits of the city, including for example the Velabrum, which was still navigated by boat at the end of the first century , and ²⁷ Galen noted that at Pergamum in Asia Minor the rich lived on the hill (Nutton (2000

b

: 70) ).