Manhunt: The Ten-Year Search for Bin Laden--From 9/11 to Abbottabad (34 page)

Read Manhunt: The Ten-Year Search for Bin Laden--From 9/11 to Abbottabad Online

Authors: Peter L. Bergen

Tags: #Intelligence & Espionage, #Political Freedom & Security, #21st Century, #United States, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #History

General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, the chief of staff of the Pakistan army and the most powerful man in the nation. Having helped to forge a “strategic partnership” with the U.S., he felt betrayed that no one in the U.S. government had warned him of the raid on the Abbottabad compound.

AAMIR QURESHI/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

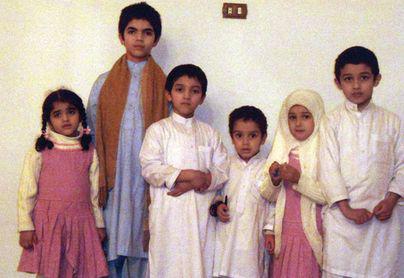

The three children at left, Fatima, age five; Abdullah, age twelve; and Hamza, age seven, are grandchildren of bin Laden. The three on the right, Hussain, age three; Zainab, age five; and Ibraheem, age eight, are the youngest of bin Laden’s twenty-four children. Hussain and Zainab were born while bin Laden was living in Abbottabad.

THE SUNDAY TIMES/NI SYNDICATION

A crowd built in front of the White House to cheer the news that bin Laden was dead.

BILL CLARK/ROLL CALL

Activists of Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan (JI) chanted slogans as they marched during an anti-U.S. protest on May 6, 2011, in Peshawar, condemning the operation that killed bin Laden. Protests like this one were limited to supporters of hardline religious groups and were not well attended.

A MAJEED/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

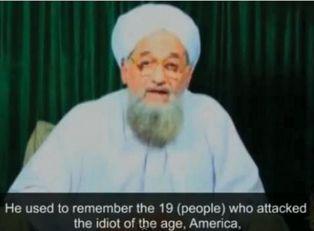

Bin Laden’s successor as the head of al-Qaeda, Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, in a video released on November 16, 2011, in which he praises bin Laden for his kindness, generosity, and loyalty.

The stars on the Memorial Wall at CIA headquarters represent Agency employees who were killed in the line of duty, including two dozen who died in the decade after 9/11.

CIA

Protesters wave Egyptian flags at Cairo’s Tahrir Square on March 11, 2011. Bin Laden’s men and his ideas were notably absent from the revolutions that roiled the Middle East in 2011.

MAHMUD HAMS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

EPILOGUE

THE TWILIGHT OF AL-QAEDA

J

UST AS WE CANNOT

understand why the French army risked marching to Moscow during the frigid Russian winter of 1812 without comprehending the ambitions of Napoleon, we cannot understand al-Qaeda or 9/11 without Osama bin Laden. It was bin Laden who conceived of al-Qaeda during the waning days of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, and he was its unquestioned leader from its

inception in Peshawar in August 1988 until the day he was killed, more than two decades later. And it was bin Laden who came up with the strategy of attacking the United States in order to end its influence in the Muslim world—a strategy that ultimately fared about as well as the march on Moscow did for Napoleon. Instead of forcing the United States to pull out of the Middle East as bin Laden had predicted it would after the 9/11 attacks, the United States, together with its allies, largely destroyed al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and later invaded Iraq, while simultaneously building massive American military bases in Muslim countries such as Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain.

If bin Laden’s strategy of attacking the United States was largely

a failure, his ideas may have more lasting currency, at least among a small minority in the Muslim world. Like many of history’s most effective leaders, bin Laden told a simple story about the world that his followers—from Jakarta to London—found easy to grasp. In his telling there was a conspiracy by the West and its puppet allies in the Muslim world to destroy true Islam, a conspiracy led by the United States. Bin Laden very effectively communicated to a global audience this master narrative of a war on Islam led by America that must be avenged.

A Gallup Poll in ten Muslim countries conducted in 2005 and 2006 found that 7 percent of Muslims said the 9/11 attacks were “completely justified.” To put it another way, out of the estimated 1.2 billion Muslims in the world, about 100 million Muslims wholeheartedly endorsed bin Laden’s rationale for the 9/11 attacks and the need for Islamic revenge on the West.

One of bin Laden’s most toxic legacies is that even militant Islamist groups that don’t call themselves al-Qaeda have adopted this ideology. According to Spanish prosecutors, the Pakistani Taliban

sent a team of would-be suicide bombers to Barcelona to attack the subway system there in January 2008. A year later, the Pakistani Taliban

trained an American recruit, Faisal Shahzad, for an attack in New York. Shahzad traveled to Pakistan, where he received five days of bomb-making training in the tribal region of Waziristan. Armed with this training, Shahzad placed a bomb in an SUV and tried to detonate it in Times Square on May 1, 2010, around 6 p.m. Luckily, the bomb malfunctioned, and Shahzad was arrested two days later.

The Mumbai attacks of 2008 showed that bin Laden’s ideas about attacking Western and Jewish targets had also spread to Pakistani militant groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), which had previously focused only on Indian targets. Over a three-day period in late November 2008, LeT

carried out multiple attacks in

Mumbai, targeting five-star hotels housing Westerners and a Jewish-American community center and killing 170 people.

And al-Qaeda’s regional affiliates will also try to continue bin Laden’s bloody work. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) was responsible for attempting to bring down Northwest Flight 253 over Detroit on Christmas Day 2009 with a bomb hidden in the underwear of Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, a Nigerian recruit. A year later, AQAP

hid bombs in toner cartridges on planes bound for Chicago. The bombs were discovered only at the last moment at East Midlands Airport in the United Kingdom and in Dubai.

In September 2009, the Somali Islamist insurgent group Al-Shabaab (“the youth” in Arabic)

formally pledged allegiance to bin Laden following a two-year period in which it had recruited Somali-Americans and other U.S. Muslims to fight in the war in Somalia. After it announced its fealty to bin Laden, Shabaab was able to recruit larger numbers of foreign fighters; by one estimate

up to twelve hundred were working with the group by 2010. A year later, Shabaab controlled much of southern Somalia.

In Nigeria, a country with a substantial Muslim population, a jihadist group known as Boko Haram attacked the United Nations building in the Nigerian capital, Abuja, killing some twenty people in the summer of 2011. Since then the group has mounted a systematic campaign against Christian targets.

In 2008, there was a sense that Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) was on the verge of defeat. The American ambassador to Iraq,

Ryan Crocker, said, “You are not going to hear me say that al-Qaeda is defeated, but they’ve never been closer to defeat than they are now.” Certainly AQI had lost its ability to control large swaths of the country and a good chunk of the Sunni population as it had in 2006, but the group proved surprisingly resilient, continuing to pull off large-scale bombings in central Baghdad. And in 2012,

AQI sent foot

soldiers into Syria to fight against the regime of Bashar al-Assad, who is from a Shia sect despised as heretics by the Sunni ultrafundamentalists who make up al-Qaeda.