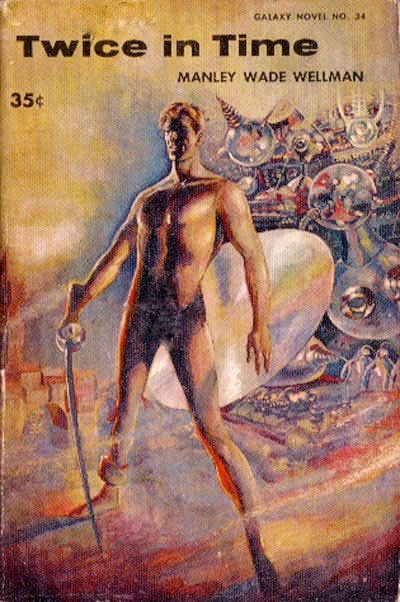

Manly Wade Wellman - Novel 1940

Read Manly Wade Wellman - Novel 1940 Online

Authors: Twice In Time (v1.1)

Twice In

Time

Manly Wade

Wellman

Contents

THE document herewith given publication was placed in the hands

of the editors in 1939. Whether or not it explains satisfactorily the strange

disappearance of Leo Thrasher near

Florence

,

Italy

,

in the spring of 1938, we do not pretend to decide.

The manuscript came to

America

in the luggage of Father David Sutton, an American priest, at the time of the recent

outbreak of war in

Europe

. Father Sutton was in

Rome

at the time, and elected to remain, in hope of helping war sufferers if his aid

should be needed. But since

Italy

remained neutral, he sent back most of his luggage to

America

by a friend. Later he sent an urgent letter, asking that this manuscript be

examined and published, if possible. It came, Father Sutton said, from the

strongroom of an immemorial theological library in

Florence

,

and was in the original casket that had apparently contained it for a long

period of time.

The priest's friend brought us both Father Sutton's letter

and the casket with the manuscript. This casket is of tarnished silver,

elaborately worked in the Renaissance manner. A plate on the lid bears this

legend, in Italian, French and Latin:

Let no man open or dispose of this casket, on peril of his

soul, before the year 1939.

Father Sutton's

New York

friends insist that if he actually wrote the letter and sent the casket, they

may be taken at face value. If it is a hoax perpetrated in his name, it is both

elaborate and senseless. In any case, it is worth the study of those who love

the curious.

Therefore, while neither affirming nor denying the truth

of what appears, herewith is given in full the purported statement of the

vanished Leo Thrasher.

The Time Reflector

THIS story, as unvarnished as I can make it, must begin

where my twentieth-century life ends —in the sitting room of the suite taken by

George Astley and myself at Tomasulo's inn, on a hill above the

Arno

.

It is the clearest of all my clouded memories of that time. April was the

month, still chilly for

Tuscany

, and

we had a charcoal fire in the grate.

I knelt among my dismantled machinery, before the charcoal

fire, testing the connections here and there.

"So that's your time-traveler, Thrasher?" said

Astley. "Like the one H. G. Wells wrote about?"

"Not in the least like the one H. G. Wells wrote

about," I said

spiritedly,

and not perhaps

without a certain resentful pride. "He described a sort of century-hurdling

mechanical horse. In its saddle you rode forward into the Judgment Day or back

to the beginning. This thing of mine will work, but as a reflector."

I peered into the great cylindrical housing that held my

lens, a carefully polished crystal of alum, more than two feet in diameter. I

smiled with satisfaction.

"It won't carry me into time," I assured. "It'll

throw me."

He leaned back in the easy chair that was too small for

him.

"I don't understand, Leo," he confessed. "Tell

me about it."

"All right—if I must," I said. I had told him so

often before. It was a bore to have to repeat what a man seemed incapable of

understanding. "The operation is comparable to that of a

burning-glass," I explained patiently, "which involves a point of light

and transfers its powers through space to another position. Here" I waved

toward the mass of mechanism "is a device that will involve an object and

transfer, or rather,

reproduce

it to another epoch in time."

"I've tried to read Einstein at least enough to think

of time as an extra dimension," ventured Astley. "But, still, I don't

follow your reasoning. You can't exist in two places at once. That's impossible

in the face of it. Yet from what I gather you can exist, you have existed, in

two separate and distinct times. For instance, you're a grown man now, but when

you were a baby—"

"That's the fourth dimension of it," I broke in.

"The baby Leo Thrasher was, in a way, only the original tip of the

fourth-dimensional me. At ten, I was a cross-section. Now I'm another, six feet

tall, eighteen inches wide, eight inches thick—and quite some more years

deep." I began to tinker with my lights. "Do you see now?"

"A little."

Astley had

produced his oldest and most odorous pipe. "You mean that this present

manifestation of you is a single corridorlike object, reaching in time from the

place of your birth—

Chicago

, wasn't

it?—to here in

Florence

."

"That's something of the truth," I granted, my

head deep in the great boxlike container that housed the electrical part of the

machine. "I exist, therefore, only once in time. But suppose this me is

taken completely out o£ Twentieth Century existence- dematerialized, recreated

in another epoch. That makes twice in time, doesn't it?"

AS I

had many times before, I thrilled to the possibility. It was my father's fault,

all this labor and dream. I had wanted to study art, had wanted to be a

painter, and he had wanted me to be an engineer. But he could not direct my

imagination. At the schools he selected, I found the wheels and belts and

motors all singing to me a song both weird and compelling.

The Machine Age was not enough of a wonder to me. I

demanded of it other wonders-miracles.

"I've read Dunne's theory of corridors in time,"

Astley was musing. "And once I saw a play about them by J. B. Priestly,

wasn't it? What's your reaction to that stuff?"

"That's one of the things I hope to find out

about," I told him. "Of course, I think that there's only the one

corridor, and I'm going to travel down it—or duck out at one point, I

mean

, and reenter farther along.

What I'd like to do would be to reappear in

Florence

of another age,

Florence

of the

Renaissance."

Astley nodded. He preferred the French Gothic period,

because of the swords and the ballads, but he understood my enthusiasm for

Renaissance Italy—to me, the age and home of the greatest painters, poets,

philosophers of all times.

"Then what?" he encouraged me, gaining interest.

"I'll paint a picture—a good one, I hope.

A picture that will properly grace a chapel or church or gallery, a

picture that will be kept for four centuries or more.

Preferably it will

be a

mural, that

cannot be plundered or destroyed without

tearing down a whole important building. When it's finished, I'll come back to

this time, to this hour almost. Of course, I'll have to build myself a new

time-reflector where I am, because it will be impossible to take this one with

me."

"And we'll go together to the chapel or church or

gallery, and look at your Leo Thrasher work of art?" asked Astley. He lighted

his pipe. "It will be your footprint in the sands of another time

. "

Isn't that what you mean?"

"Exactly.

Evidence

that I've been twice in time."

I sighed, with a feeling of rapture,

because for a moment I fancied the adventure already accomplished.

"If I'm not able to do a picture," I told him,

"I'll make my mark—initials or a cross. Cut it in the plinth of a statue,

scratch it on the boards at the back of the Mona Lisa or other paintings that I

know will survive. It will be almost as good a proof." I smiled.

"However, I daresay they'll let me paint. I have a gift that way."

"Perhaps because you're lefthanded," Astley smiled

at me through the blue smoke. "But one thing—in Renaissance Italy, won't

your height and buttery hair

be

out of place?"

"Not among Fifteenth-Century Tuscans," I said

confidently. "There were many with yellow hair and blue eyes. Look at the

old Florentine portraits in any art gallery. Look at the streets of

Florence

today. Not all of those big tawny people are foreigners."

As I talked, I was reassembling my machinery that we had

brought with great care from my native

America

to this spot that I had long since chosen as the obvious place for my

experiment.

The apparatus took shape under my hands. The open

framework, six feet high, as many feet long, and a yard wide, was of metal rods

painstakingly milled to micrometric proportion in

Germany

.

At one end, on a succession of racks, were arranged my

ray-generator, with its light bulbs, specially made with vanadium filaments in

America

.

My cameralike device which concentrated the time-reflection power had been

assembled from parts made by English, German and Swiss experts. And then there

was the lens of alum with its housing, as big and heavy as a piece of

water-main, which I now lifted carefully and clamped into place at the front of

the camera.

ASTLEY stared, and drew on his pipe. It was plain enough

that he looked tolerantly on all my labor as well as my talk, and that he

believed the whole experiment was something of which I would quickly tire.

Though he had been complaisant enough about coming with me and lending what aid

he could to my secret experiment.

"That business you're setting up there looks like the

kind of thing science fictionists write about," he said.

"It's exactly the kind of thing they write

about," I assured him. "As a matter of fact, science fiction has given

me plenty of inspiration, and more than a little information, while I've been

making it. But this is practical and material, Astley, not imaginary."

He had not long to wait to witness the truth of that,

though his phlegmatic nature could never have understood the tenseness that was

making my nerves taut as a spring trap. I knew, however, that nerve strain was to

be expected, for I was nearing the actuality of the experiment to which I had

long given my heart and soul.

I said nothing more, because now, within the tick of

seconds I would know whether my dream could be a reality or if, in fact, that

was all I had toiled and anguished for—a dream!

I am not sure—how could I be certain?—whether my hands

were steady when the great moment came. I know vaguely that my hands did reach

out.

I pressed a switch. At the other end of the framework

there sprang into view a paper-thin sheet of misty vapor, like a piece of

fabric stretched between the

rectangle

of rods. I

could be excused for the theatricality of my gesture.

"Behold the curtain!" I said. "When I

concentrate my rays upon it, all is ready. I need only walk through." I stepped

back. "Five minutes for it to warm up, and I'm off into the past."

I began to take off my clothes, folding them carefully;

the tweed suit, the

necktie

of wine-colored silk. "I

can be reflected through time," I said with a touch of whimsicality,

"but my new clothes must stay here." And more seriously: "I

can't count on molecules to approximate them at the other end of the

business."

"You can't count on molecules to approximate your

body, either," challenged Astley.

I knew that he was not as stolid as he was trying to

appear, for his pipe had gone out, and he was filling it, and I could see that

his hands shook a trifle. He was beginning to wonder whether to take me

seriously or not.

Unimaginative Astley!

"All my diggings into old records at the Biblioteca

Nazionale, yonder in town, have been to find those needed molecules," I

told him. "Look at those notes on the table beside you."

He turned in his big arm-chair—it was none too big for

him, at that—and picked up the jumble of papers that lay there. "You've

written a date at the top of this one," he said as he shuffled them.

"'April Thirtieth, Fourteen-seventy.'

And below it you've

jotted down something I don't

follow :

*Mithraic

ceremony —rain prayer—ox on altar'."

"Which sums up everything," I said, pulling off

my shoes. "Right here right at this inn, which I hunted up for the purpose

of my experiment—a group of cultists gathered on April Thirtieth, Fourteen -

seventy.

Just four hundred and sixty-eight years ago

today."

I leaned over to look at the time-gauge on my camera.

"I'm set for that, exactly."

"Cultists?" repeated Astley, whom I knew from of

old

is apt to clamp mentally upon a single word that

interests him. "What sort of cultists?"

"Contemporaries called them sorcerers and

Satanists," I told him. "But probably they had some sort of hand-me-down

paganism from old Roman days. Something like the worship of Mithras *

At

any rate, they were sacrificing an ox on that day, trying

to bring rain down on their vineyards. I have figured it out like this—if they needed

rain, then that particular April thirtieth must have been bright and sunny,

ideal for my reflection apparatus. They had an ox on the altar, and from its

substance I can reassemble my own tissues to house my personality again. The

original molecules have, of course, dissipated somewhere along the route of the

process in time. Is that all clear?"

ASTLEY nodded slowly, and I stood up without a stitch of clothing.

A pier-glass gave me back a tall pink image, lank but well muscled, crowned

with ruffled hair of tawny gold.

"Well, old man," I said, with what nonchalance I

could, through every nerve in me was tingling, "the machinery's humming.

Here I step into the past."

My companion clamped his pipe between his teeth, but did

not light it again. I could still see the disbelief in his eyes.

"I hope you know what you're about, and won't do

yourself much damage with that thing," he grumbled. "Putting yourself

into such a position isn't like experimenting with rats or guinea pigs, you

know."

"I haven't experimented with rats or guinea

pigs," I informed him, and stepped into the open framework. I turned on

another switch, and through the lens of alum

flowed

an

icyblue light, full of tiny flakes that did not warm my naked skin.

* Charles Godfrey Leiand, in his important work, "

Aradia ;

or the Gospel of the Witches of Italy," traces

connections between witchcraft and the elder pagan faiths of

Rome

.

Mono Lisa

"As a matter of fact," I said in what I was sure

was a parting message, "I've never experimented with anything. Astley, old

boy, you are about to see the first operation of my time reflector upon any

living organism."

Astley leaned forward, concern at last springing out all

over his face. "If anything happens," he protested quickly,

"your family—"

"I have no family.

All dead."

With a lifted hand I forestalled what else he was going to say. "Goodbye,

Astley. Tomorrow, at this time, have a fresh veal carcass, or a fat pig,

brought here. That's for me to materialize myself back."

And I stepped two paces forward, into and through the

misty veil. At once I felt a helpless lightness, as though whisked off my feet

by a great wave of the ocean. Glancing quickly behind me, momentarily I saw the

room and all in it, but somehow vague and transparent—the fading image of the

walls, the windows, my openwork reflector-apparatus, Astley starting to his

feet from the armchair.

Then all vanished into white light.