Massacre in West Cork (18 page)

Read Massacre in West Cork Online

Authors: Barry Keane

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Ireland, #irish ira, #ireland in 1922, #protestant ireland, #what is the history of ireland, #1922 Ireland, #history of Ireland

However, the consequences of the Ballygroman killings did not end with the Woods and O’Neill families.

Still, it is the primary right of men to die and kill for the land they live in, and to punish with exceptional severity all members of their own race who have warmed their hands at the invaders’ hearth.

Winston Churchill

1

The (Dunmanway Murders) are being undertaken because the Southern Irish native is a barbarous savage with a strong inherent penchant for murder which those responsible for him – his priests, his politicians and his alleged organs of enlightenment – have not only failed to eradicate from his primitive bosom, but have actually fostered.

Morning Post

2

The Ballygroman killings were bad enough on their own, but over the next four nights (26–29 April 1922) there were widespread attacks on loyalists across West Cork. The motive for these attacks has already generated huge debate within Irish history regarding the interpretation of evidence. As the actual evidence tends to get lost in the debate, I have chosen to concentrate on that evidence here. In total, nine Protestants were killed between the towns of Dunmanway and Bandon in West Cork, one in Clonakilty and another was shot and badly injured in Murragh, on the main road between Bandon and Ballineen. If the Ballygroman killings are included, as well as those of four British soldiers who were kidnapped and executed while on intelligence work at Macroom, twenty-five kilometres north of Dunmanway, this brings the total of dead to seventeen.

3

If those who were targeted but not killed are included, the figure rises to at least thirty. In Dunmanway, for example, William Jagoe’s house was attacked and if he had been at home it is probable that he too would have been shot. George ‘Appy’ Bryan had a gun placed to his head but the gun jammed and he fled. Local schoolteacher William Morrison also escaped from attack, as did John McCarthy and Tom Sullivan.

4

This level of attack on defenceless civilians was unheard of in the Irish War of Independence, and as virtually all the victims were Protestant it raised fears that the killings were sectarian.

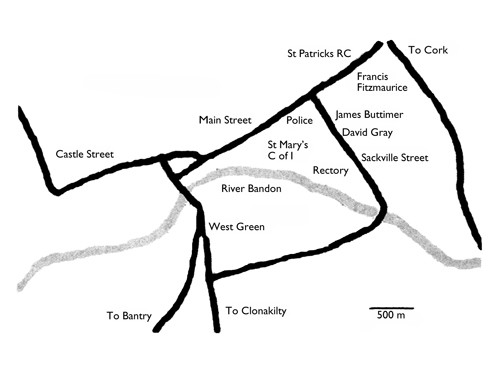

Locations of killings in Dunmanway © Barry Keane

Specifically, on the night of 26–27 April three men were shot and killed in Dunmanway: local solicitor Francis Fitzmaurice was killed at 12.15 a.m., chemist David Gray at 1 a.m. and retired draper James Buttimer at 1.20 a.m. All were shot on their doorsteps. According to David Gray’s wife, his killers called him a Free Stater a number of times while they were shooting him. All this took place within a hundred metres of the police station in Dunmanway, which was controlled by the anti-Treaty IRA under Peadar Kearney, who failed to stop them. During the second night, 27–28 April, John Chinnery and Robert Howe were shot in Castletown-Kinneigh to the north of Ballineen at around 1.30 a.m. according to the

Cork & County Eagle

of 6 May, or 10.30 p.m. for Howe according to

The Irish Times

of 2 May. Chinnery and Howe were next-door neighbours. The pattern was the same in both cases. Howe’s wife, Catherine, gave evidence to his inquest that he was attacked in the bedroom of his house at around 10.30 p.m., having refused to harness a horse. When he refused a second time he was shot and killed. John Chinnery was shot while harnessing a horse for the raiders. On the same night Alexander Gerald McKinley, who was sick in bed, was shot in Ballineen after 1.30 a.m. His aunt was put out of the house and he was shot in the back of the head. At Caher, three kilometres west of Ballineen, John Buttimer and his farm servant James Greenfield were shot at 2 a.m.:

Frances Buttimer (John’s wife) stated that she heard noise and shots – Her son said ‘we are being attacked’, and jumped out of bed. She became weak, but recovered quickly. She met her husband on the landing, and said ‘for God’s sake get out’, and he said ‘shure I can’t’. Greenfield called on her to stay with him. She came down stairs, and met a man and said ‘Where are you going?’ He replied ‘Where are the men?’ She said ‘I do not know. What do you want them for?’ He said ‘only very little’. She said to him ‘Take my house, my money, or myself and spare the men’. She put her hand to his chest to keep him back, and he pushed past her, and went upstairs calling on her husband in a blasphemous manner to come down. She went away from the house and returned after a while and met a man and said ‘You have killed them, but you cannot kill their souls’.

5

She went into the house and found her husband dead in a sitting position in Greenfield’s room, and Greenfield was dead in bed.

6

Church of Ireland curate Rev. Ralph Harbord was shot (but not killed) in Murragh on the same night. Robert Nagle was shot and killed in Clonakilty after 11 p.m. Two men called to the house and, having questioned Robert about his age, they doused the light in his bedroom and shot him. His mother, who was in the house and witnessed the events, said one of the killers was drunk. He was shot in place of his father, Tom, the caretaker of the Masonic Hall, and on the same night the Masonic Hall was burned.

7

The final victim was John Bradfield of Killowen Cottage at Cahoo, four kilometres west of Bandon. He was killed at 11 p.m. on the night of 29–30 April in place of his brother William:

8

Elizabeth Shorten (his sister) … stated that at 11 p.m. on Saturday a group of men called to the door to get a horse and car. Her brother got out of bed, but did not answer. They knocked on the door and broke the windows. On entering the dining room, they asked for her brother William. They entered John’s room and she heard a shot. John was unable to walk without sticks.

9

More than thirty men of both main religions were targeted, shot at or forced to flee over the same three days, but all those killed were Protestant. As the killings continued into a third night, the officer in charge of the Royal Navy based at Queenstown (Cobh) began putting contingency plans in place to evacuate loyalists and Protestants from southern Irish ports.

10

He even suggested that this might well be the start of a pogrom.

Many scholars have recognised the importance of the information contained in the inquest report into the killing of John Buttimer and James Greenfield in Caher. Others give less weight to Frances Buttimer’s account. Anyone who reads her testimony should conclude that the killer was calm and focused on his mission. Her bravery – in putting her hand out to bar the way of an armed man who had broken into her home in the middle of the night looking for ‘the men’ – is heroic. There was a general prohibition on killing women, but it is extraordinary that the gunman did not harm her person in any way. Clearly the Buttimer family home was targeted for a reason: it was awkward to get to and was surrounded by other Protestant homes that were more accessible. If this was a sectarian attack, why did the attackers walk past those other homes and target the Buttimers? The killers knew who they wanted, and they apparently pursued the son, who escaped them, relentlessly, though the only source for this is an anonymous interview.

Theories about the ‘who and why’ of the events in Dunmanway have been proposed for a long time. Henry Kingsmill Moore was the principal of the Church of Ireland teacher-training college in Kildare Place, Dublin, for much of this period and was one of the first to use the term ‘Dunmanway massacre’, in his autobiography written in 1930.

11

He stated that the massacre was in response to the Belfast ‘pogroms’, and gave details of the events ‘from someone who was there’.

The traditional view was that the killings ‘violently in conflict with the traditions and principles of the Republican Army’ were an aberration and a stain on the West Cork IRA.

12

At the time there was a dispute between Cork Corporation and Cork County Council as to whether the killing of Michael O’Neill was a possible trigger. However, in the absence of any other evidence, local people concluded that the killings were a response to the Belfast ‘pogroms’.

It was not until 1993 that any serious attempt was made to challenge this traditional view. In truth, most people had forgotten about the incident. Certainly, it was mentioned to me in passing when I was talking to Protestants in West Cork in 1986–87 about migration, but details were sketchy and people were far more interested in hammering home the point that the Ne Temere decree of 1908 was the single greatest threat to the native Protestant community during the period.

13

In 1990 Kevin Myers, the person who kick-started this debate, declared in

The Irish Times

that leading West Cork IRA members Peadar Kearney and Sonny Crowley were among the killers, without presenting any evidence to back up his claims.

14

Tim Pat Coogan, in his 1992 book

The Man who Made Ireland: the Life and Death of Michael Collins

, ascribed the killings to ‘latent sectarianism of centuries of ballads and landlordism’, also without presenting any direct evidence.

15

It was not until Peter Hart entered the debate that a sustained challenge to the orthodoxy was attempted. Because it is not too strong a claim to suggest that civil war in Irish historical studies broke out in 1998 with the publication of Hart’s book The IRA and Its Enemies, it is worth looking at his arguments and the counter-arguments in some detail.

At first Hart’s book was received with critical acclaim and, as readers assumed that all of his assertions were supported by the copious and meticulous referencing, there was no reason not to be generous in praise of the book. Indeed Kevin Myers, writing in The Irish Times, was ecstatic at the publication and flagged the book repeatedly in his ‘Irishman’s diary’.

16

When discussing the murders of 26–29 April 1922, Hart argued that in revenge for Michael O’Neill’s death, the IRA – as a result of a process of intimidation and exclusion which had increased during the War of Independence – punished and attempted to drive out members of the minority Protestant community because they were Protestant. He concluded that ‘the Catholic reaction to the murders was so muted’ because Protestants had become outsiders.

17

As Hart apparently had identified a host of sources to back up his arguments, he told a seemingly accurate story of what happened both before and after the killings, and the inherent claim of sectarianism had to be accepted, no matter how unpalatable this was for nationalists and the descendants of the 3rd Cork Brigade. Despite his use of overly dramatic language, a society, brought up on the belief that the War of Independence was the final act in a long struggle to cast off the imperialist yoke, was being challenged to accept that sectarian motives were at the heart of it in West Cork and that ‘they had closed ranks’ against their neighbours when they had needed them.

18

Hart explicitly, for example, rejected the possibility that the motive for the Dunmanway killings was that those shot had been part of a ‘Loyalist plot’. Based on his research, common sense suggested that his fundamental argument about the Dunmanway massacre was accurate: ‘In the end, however, the fact of the victims’ religion is inescapable. These men were shot because they were Protestant.’

19

Hart said that Protestants had little information to give, and that if they were targeted as spies it was a result of paranoia brought on ‘by a welter of suspicions and a sectarian and ethnic subtext’.

20

Not long after publication, however, local historian Meda Ryan, Brian Murphy PhD (a Glenstal Abbey priest), the Millstreet-based Aubane Historical Society and, of course, all strands of Sinn Féin began to criticise Hart’s work. They were dismissed as ‘cranks’ or ‘republican sympathisers’

21

until Murphy showed that Hart had selectively quoted the British Army intelligence document that was central to his argument.

22

Instead of pointing out that Bandon was an exceptional area of loyalist co-operation with the authorities, Hart stated that the complete opposite was the case.

23

In more recent years other historians – including former colleagues, some of whom had previously vigorously defended him – have also questioned the accuracy of Hart’s work.

24

The quotation identified by Murphy was: