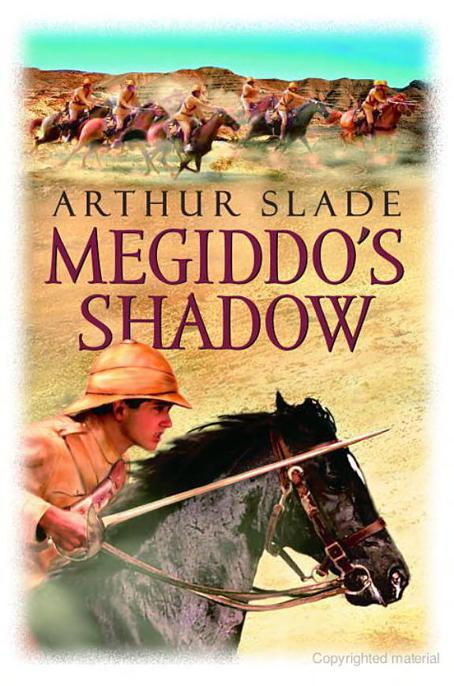

Megiddo's Shadow

Authors: Arthur Slade

Also by Arthur Slade

DUST

TRIBES

This novel is dedicated to the memory of:

Corporal Edmund Hercules Slade, 1867-1949

Trooper Cecil Henry Edmund Slade, 1891-1949

Lance Corporal Arthur Hercules Slade, 1893-1975

Trooper Herbert George Slade, 1894-1962

Private Percy james Slade, 1897-1918 (K1A)

And to all those who fought in the Great War in all armies

.

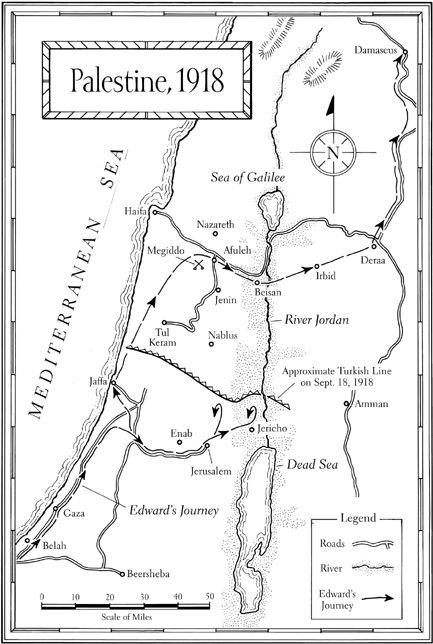

Author's NoteThe names of locations used in this book are as they appear on British military maps from the time period. Many of the names have changed since that time.

Oh! we don't want to lose you

But we think you ought to go

,

For your King and your Country

Both need you so

.

We shall want you and miss you

,

But with all our might and main

We shall cheer you, thank you, kiss you

When you come home again

.

“Your King and Country Want You”

Lyrics by Paul Rubens

T

he letter was stained with mud from France, but there was a British army stamp in the corner, and the handwriting looked fancy and official. Maybe Hector had won a medal! He'd finally given the Huns a good, hard punch on the nose.

I left the general store, nearly tripping on the sidewalk planks as I searched the envelope for clues about its contents. I wanted to rip it open, but it had been addressed to Dad. My breath turned to frost in the October air. Hector must've jumped out of the trenches and taken a machine-gun nest, or perhaps he'd captured a bunch of Germans. He'd joined up in 1916, so he'd been over there for more than a year; lots of time to do something heroic. I jogged the half mile to our farm, watching for our white and green house to appear on the other side of the hill, with the rolling prairie spread out beyond it.

Maybe Hector would be getting a Victoria Cross pinned to his chest. He would make the papers all across Canada.

I stopped in my tracks. I fingered the thin envelope, my mouth dry.

What if it's not a medal. What if

… I wouldn't let myself think the words.

If he'd fallen in France I'd surely have felt something deep in my heart, even thousands of miles away here in Saskatchewan.

Such dark thoughts had made my legs numb. I leaned against our sign that said BATHE FAMILY FARM. Father had carved it to put a name to the fields he'd cut out of the prairie. Land he intended to pass on to us boys.

No Hun bullet would ever kill Hector, but perhaps he'd been so badly wounded that he couldn't even pick up a pen.

My hand shook as I flicked open my pocketknife and slit the envelope. I'd tell Dad I just couldn't wait to read the good news.

I scanned the first few lines.

R.S. Major

27/09/17

ISth Canadian Batt

B.E.F

.Dear Mr. Wilfred Bathe

,You will no doubt wonder who this is writing to you. I will try to explain as well as I can; I am the regimental sergeant major of the above battalion. I have a very painful duty to perform in

—

My heart stopped. It wasn't just a “painful duty,” but a

“very

painful duty,” and I knew what had to follow. I sucked in a rattling breath. And another.

Oh, God. Oh, no

.

I forced myself to move toward the house. It was an eternity before I got there. I opened the door, the squeaking hinge unusually loud. I passed through the empty hall and up the worn stairs, glancing at the Union Jack that hung on the wall. I pulled myself up with the rail. I'd gone from sixteen to a hundred years old.

At the top of the landing I stopped to wipe my icy, sweaty palms on my overalls. I glanced at the oval photograph of Dad in his dragoons uniform, medals from the South African war glittering on his chest. Hung next to him was the picture of Mother in her Sunday best, and the thought of her made my legs go weak. It was a blessing God had taken her; today would have broken Mom's heart. Beside her was a photograph of Hector and me, when he was fourteen and I was twelve. I looked away and tried to swallow the lump in my throat.

Maybe he'd just been terribly wounded, his bright green eyes blinded by gas. That was why he couldn't write. Or perhaps his arm had been blown off. If so, when he got home he would still be able to fork hay with one hand. I'd help him. I would.

I knocked and entered the master bedroom. The stink of pee and old sweat hung in the air, a sign of how weak Dad was now. He lay sleeping, sheets pulled up to his neck, cheekbones sticking out of his long, pale face as though he were starving. His once proud and bushy mustache was limp and stringy.

I sat on the wooden chair and waited, my hands still trembling. Dad had been bedridden for seven months, leaving me to seed, harvest, and do the chores. In March, on the anniversary of Mom's death, he stayed in bed all day, as prickly as a cactus. He didn't get up the next day, or the next. In fact, he didn't get up at all. He gave up on everything. The man I'd seen flip and pin a calf in a heartbeat couldn't even pull himself out of bed.

It wasn't the first time he'd been bedridden. Once or twice a year he'd go all dour and stay in bed. Mom would give him a day or two before she grabbed his work clothes and boots and goaded him to his feet. After her funeral he spent three days in bed. On the fourth day Hector set Dad's work clothes and boots on the end of the bed. Dad was out to the barn within an hour, not saying a word.

This time, I'd tried the same trick after the first week, but no luck. When it came to Dad, Hector had the magic touch; it'd always been that way. All I could do was call Dr. Fusil, an old man with sharp eyes. This was, of course, against Father's wishes.

“Wilfred's body is fine,” Dr. Fusil said out on the front porch after the visit. He slowly pulled on his coat. “His mind, though, is troubled. If his condition worsens and he refuses all food and water, there's a sanitarium in Regina I could recommend. That'd leave you with a heavy load, though.”

I'm already doing all the work!

I felt like shouting. But instead, I only shrugged, and the doctor putted away in his Model T.

Now, I sat back in the chair, making it creak.

“What's in your hand, Edward?” Father asked.

His gray eyes searched mine. I could see every long day he'd worked.

“It's a letter from Hector's major.”

Father closed his eyes. Several moments passed before he rasped, “Read it, will you?”

I unfolded the letter. The writing was perfect; not even a smear. I had to swallow several times to ensure my voice wouldn't crack.

R.S. Major

27/09/17

ISth Canadian Batt

B.E.F

.Dear Mr. Wilfred Bathe

,You will no doubt wonder who this is writing to you. I will try to explain as well as I can; I am the regimental sergeant major of the above battalion. I have a very painful duty to perform in telling you of the death of your son Hector. He was my batman, as no doubt he will have previously told you in his letters home. He spoke very highly of you and asked me to write should the worst come to pass

.We went into the attack on the 26th day of this month, and Hector was killed by a rifle bullet that struck him right through the heart. Death was instantaneous. This happened just as we were approaching the German front lines. You have my most sincere and deep sympathy for the loss of your brave

lad; no one knows better than I of his qualities as a soldier. Believe me, I feel the loss very much. I gave him instructions to stay behind and come up after the attack and his reply was “Major, wherever you go I am going too.” He was made of the right stuff. You will be officially notified as to the location of his grave and I am sure if there is any more information I can give you I shall only be too pleased if it is in my power

.Yours sincerely,

F. Gledhill

My throat was dry and my body numb. I'd become hardened clay. No, not quite. My hand was still shaking.

A tear slid down into the wrinkles on my father's face. I'd never seen him cry, not even when he'd split his hand open chopping wood. Not even at Mom's funeral.

We should have had a telegram, but someone had forgotten us. Hector had died almost two weeks earlier. All this time I'd thought he was alive.

I squeezed the arm of the chair and nearly ripped it off. It wasn't right! My father was broken and my brother dead. “I'll join up, the moment I'm eighteen,” I'd promised Hector. “I have to keep you out of trouble!” But now I wouldn't wait until I was eighteen; the Huns could be pissing on his grave as I sat here waiting for Dad to speak.