Michael Walsh Bundle (73 page)

Read Michael Walsh Bundle Online

Authors: Michael Walsh

C

HAPTER

S

EVEN

HAPTER

S

EVEN

Los Angeles

The cool interior was a welcome relief from the heat. The Spanish knew what they were doing when they invented California architecture. Space, air, breezeways, and let nature do the rest. Or God. Whichever.

Earthquakesâwell, they were the work of the devil, which is why this particular cathedral had been abandoned in favor of the modern monstrosity up the hill, across from the Music Center.

God had moved. The new Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels sat up on what was left of Bunker Hill, looming over the Hollywood Freeway. There it was, the sacred and profane, back to back and belly to belly: That was Los Angeles in a nutshell, no contradiction noted or accepted. Take it or leave it, all or nothing. Mammon Found, Paradise Lost.

There was no God here. Except for the old altar, everything ecclesiastical had been stripped away, leaving only the cracked walls and rocked foundations of a building that had finally met the California earthquake code it couldn't survive or finesse.

No pews, no confessionals. Even the stained-glass windows had been removed; from the side; the cathedral looked like the gap-toothed mouth of one of the bums out on Second Street, who drank Ripple and screamed obscenities at the few civil-service souls who passed by on their way to and from their cubicles and the tacqueria.

The empty church was as eerie as an AA meeting with no drunks. Funny, he'd thought the conversion to the arts center was long-since complete.

“Mr. Harris? Mr. Bert Harris?” Male, Hispanic, early thirtiesâthis much he knew without even turning around. “I'm Father Gonsalves.”

Looking back on it, that should have been the tip-off right there. Father Last Name in a world that had lost both its faith and its surnames. Not Father Tom, or Father Mike or Father Ed. Priests hadn't used their last names since the Primate was a pup.

The guy looked straight enough. Black cassock, white dog collar, the usual outfit. Good, firm handshake. Devlin liked that.

“I don't know how much Jacinta has told you,” Father Gonsalves began, his words echoing in the vaulted space.

“Just this,” replied Devlin. He opened his left hand and displayed the rose petal. “Which is, I guess, all I need to know.”

Father Gonsalves moved toward the altar, the only flat surface other than the floor. Its marble top was pebbled from years, decades, of use. Instead of a chalice, there was a small pile of folders and documents lying atop it.

“I don't know how much you know about miraclesâ”

“I believe them when I see them, and that's not very often. As in never.”

“Good. May I ask if you're a Catholic?” said the padre.

“You may. I'm not.”

“Not anymore, you mean.”

“Guesstimation or revelation?”

“Have a look at this, please.”

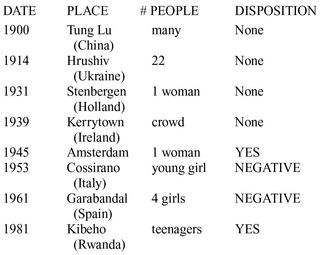

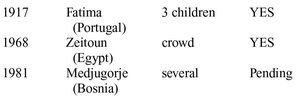

It was a computer printout, tens of pages in length. Dates, locations, number of people. Starting in 1900 and running up to the present. Devlin scanned it quickly, his eyes picking out various incidents:

He handed the pages back to the padre. “Looks like an epidemiological study for some sort of disease. An outbreak of some kind. What was it? Hemorrhagic fever? Smallpox?”

Father Gonsalves indicated something on one of the pages. “Note particularly the concatenation in Spain in 1931. Ezquioga, Izurdiagaâ”

“Basque country. Just before the civil war. People see things when they're crazy.”

The priest shot him an impressed look. “Very good. Zumarraga, Ormaiztegui, Albiztur, Barcelona, Iraneta. All in Spain, within the same year.”

“A mental illness of some kind? Mass psychosis, brought on by the proximity of war? If you look at the datesâ”

“You're a data miner, Mr. Harris. You figure it out.”

Interesting choice of words. “Data mining” was not a term in common parlance. Most people had no idea what it meant. Seelye must have put him up to this.

He shook his head. “Too small a sample. No way to create an association algorithm. Probably need to use an API . . .”

“Let me help you.” Father Gonsalves leafed through the pages, found what he was looking for, pointedâ

“Are you familiar with California City?”

“North of Lancaster, in the Mojave.” Hell on earth.

“It will take you a couple of hours to get there. Although at that time of day, the traffic will mostly be coming the other way.”

Was he for real? Traffic in L.A. ran in all directions pretty much twenty-four hours a day, six days a week. The myth of a “rush hour” that flowed one way in the morning and the other way in the evening was strictly an East Coast import, one of the things displaced people from the wrong side of the Mississippi clung to, like faith, to help them rationalize the irrational world that was God's country. He'd seen the Sepulveda Pass clogged at 4

A.M.

, and once sped west on the Santa Monica Freeway on a fine spring day without braking once between downtown and the beach. Miracles sometimes did happen. Just often enough to keep the suckers in the tent.

A.M.

, and once sped west on the Santa Monica Freeway on a fine spring day without braking once between downtown and the beach. Miracles sometimes did happen. Just often enough to keep the suckers in the tent.

“I haven't agreed to anything yet,” Devlin objected.

“Sure you have,” replied the priest. “You're here, aren't you?”

They stood there staring at each other. Jacinta was still nowhere to be seen. Father Gonsalves gestured at the floor as he reached for the stack of papers. “I'm sorry, the rectory's . . . closed to visitors.”

Devlin sat on the floor; the seat of his trousers would have to like it or lump it. The padre squatted like a Southeast Asian, rocking back on his haunches. That was a position Devlin had never quite mastered, couldn't have even had he wanted to. It made him feel like the last refugee not to make it out of Saigon, and he had not yet fallen that low. Not quite.

“There's more pictures. Do you want to see them?”

“Not unless you tell me what this is all about.”

“Listen to this.” Father Gonsalves closed his eyes and recited from memory. “ âDear children! This is a time of great graces, but also a time of great trials for all those who desire to follow the way of peace. Again I call on you to pray, pray, prayânot with words, but with your heart. I desire to give you peace, and that you carry it in your hearts and give it to others, until God's peace begins to rule the world.' She said that. Hereâ”

More pictures. Not the desert: green hills, snowy mountains. A church with twin spires. “That was in 2002. Keep lookingâ”

A rocky, treeless hillside. Euro-hovels. A million Arabs in mufti, looking up at the sky. Skyscraper windows, sunlight glinting. A saltwater stain on a highway underpass, before which stood a makeshift altar, adorned with candles. And icons.

“You see? We needâ”

“We?”

“âto know whether she's real. Jacinta showed you the pictures from California City.” The pictures in the desert. “Have you ever heard of Juan Diego?”

He thought for a moment; even though he wasn't originally from California, he remembered something about a baptized Indian, hundreds of years ago, somewhere in Mexico, who had an encounterâprobably peyote-fueledâwith a beautiful woman.

“She gave him roses and told him to go to the bishop in what is now Mexico City. And when he opened his

tilma

âher image was imprinted on his cloak. We call her Our Lady of Guadalupe. But it's not that Juan Diego I'm talking about.”

tilma

âher image was imprinted on his cloak. We call her Our Lady of Guadalupe. But it's not that Juan Diego I'm talking about.”

Instinctively, Devlin looked at the rose petal he was still carrying in his hand as the priest fished a photo out of his stack. A dour

bracero

, by the look of him, Zapata mustache, floppy hat, holding a rosary. A group of people were kneeling beside him, praying, in the desert. In the background, he could make out a fenced-off area of white rocks with a sign in front of them.

bracero

, by the look of him, Zapata mustache, floppy hat, holding a rosary. A group of people were kneeling beside him, praying, in the desert. In the background, he could make out a fenced-off area of white rocks with a sign in front of them.

The floor was even less comfortable than it looked. Devlin rose, brushing off his rump. “Sorry, padre, but I don't believe in fairy tales, Bible stories, global warming, or the Dodgers' chances this year.”

His answer seemed to please the priest. “That's why we picked you.” He waved the pages as if fanning himself. “A string of negatives and no decisionsâexactly the way the church prefers it. As a person of Mexican descent it embarrasses me to say this, but there is no limit to the imagination of superstitious peasants.” He handed Devlin a couple of folders. “The data's all in here. Mine it”

Devlin got the picture. “Devil's Advocate, huh? Debunk and demolish. Scrape the holy mold off the taco, so to speak.”

“More like Serpent's Advocate.”

“Or the Great Red Dragon's.”

“You read the Bible.”

“Only in hotel rooms. Scripture's for Protestants.”

“I thought you said you weren't Catholic.”

“You don't have to be Catholic not to read the Bible.”

“Armando can drive you, if you'd like.”

So that was his name. “Armando's sleeping.”

“Twenty thousand dollars ought to cover it. Half now, half upon receipt of your . . . thoroughly mined . . . report.”

The padre sprang up from his squatting position and extended his hand. It had a stuffed envelope in it.

Footfalls echoing, they walked toward the front doors. “One last question,” said the priest, yanking at the heavy wooden portal.

“Shoot.” The western sunlight hit him right in the eyes.

“Isn't it rather hot for that suit?”

Not a question he hadn't heard before. Nobody wore suits in Los Angeles anymore, except lawyers and agents, and even the lawyers took off their ties once they made partner, or on Fridays, whichever came first.

“Since when does hell have a dress code?”

The doors closed behind him. The bums were still homeless. The Escalade was waiting outside, a passenger door open. He stepped over a couple of prone winos, and wondered how long it would be before he joined them.

His secure smartphone buzzed. He looked at the screen. A single word:

DORABELLA

Oh, Jesus.

He switched off voice contact and the browser, but left messaging on. Might as well give eternity and redemption his best shot, and yet still stay in touch with the outside world. It was the least he could do. After all, he was on his way to meet the Blessed Virgin Mary.

There was a map on the front seat, with a location in the desert outside California City circled in red. There was a Polaroid camera, loaded and ready to shootâextra film, too.

And one other thing. Actually, many other things: rose petals and hyacinths, all over the seats.

A voice from the backseat. He looked in the rearview mirror to make sure he was not seeing a ghost. But it was only Jacinta.

No time for questions. No time for thinking. Only time for believing. He wasn't sure he had that in him, but he would have to try.

Other books

Sarah Woods Mystery Series (1-6) Boxed Set by Jennifer L. Jennings

Made to Love by DL Kopp

Keeper of My Dreams (St. John Series Book 4) by Lora Thomas

Mummy's Favourite by Sarah Flint

A Short History of the World by H. G. Wells

50 Simple Soups for the Slow Cooker by Lynn Alley

Mud City by Deborah Ellis

I Haiku You by Betsy E. Snyder

Binocular Vision: New & Selected Stories by Pearlman, Edith

Denying Heaven (Room 103) by Sidebottom, D H