Mickelsson's Ghosts (108 page)

“Ah!” cried Mickelsson, shoving himself in.

“Sweet Christ!” she whispered, eyes snapping shut. Her head rocked from side to side, then tensed. Her pelvis thrust violently, consuming him. He couldn't have pulled out if he'd wished.

Now the bedroom was packed tight with ghosts, not just people but also animalsâminks, lynxes, foxesâmore than Mickelsson or Jessie could name, and there were still more at the windows, oblivious to the tumbling, roaring bones and blood, the rumbling at the door, though some had their arms or paws over their headsâboth people and animals, an occasional bird, still more beyond, some of them laughing, some looking away (Mormons, Presbyterians), some blowing their noses and brushing away tears, some of them clasping their hands or paws and softly mewing, shadowy cats, golden-eyed tigers (Marxist atheists, mournful Catholics) ⦠pitiful, empty-headed nothings complaining to be born. â¦

One of the songs sung in the fictional recital in this novel is adapted from “Agonies of Heaven,” by Hakim Yama Khayyam. For Mickelsson's philosophical broodings I am especially in debt to R. M. Hare and to Daniel C. Maguire, whose writings I frequently quote, usually in altered form. I am indebted, too, to Alasdair MacIntyre

(After Virtue)

I've borrowed ideas and good lines from various other philosophical writers and poets, past and present, notably Martin Luther (and one of his biographers, H. G. Heile), Friedrich Nietzsche, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Norman O. Brown, Martin Heidegger, the late Walter Kaufmann (who would mainly not approve of my treatment of Nietzsche), and from numerous acquaintances, friends, and loved ones, especially my wife, L. M. Rosenberg. The diligent will perhaps discover that I have additional literary sources, more than I know myself, among those sources the fiction of John Updike and Joyce Carol Oates and some of the poems of Carl Dennis. I am also indebted to Jack Wilcox, who helped remove from the story some philosophical improbabilities, suggested books I might read, and so on. Any stupidities which survive must be blamed on the characters. Where this novel touches on historical Mormonism, I am indebted mainly to two books, Fawn M. Brodie's

No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith,

and William Wise's

Massacre at Mountain Meadows: An American Legend and a Monumental Crime.

This novel's incursions into the kingdom of the peacetime and wartime nuclear industry, the various industrial-waste depositors, and so on, are based on books and articles too numerous and various to cite. I would like to express special gratitude to Craig and Alice Gilborn, of the Adirondack Museum, who gave me a place to write, as well as friendship and inspiration, and the English Department at SUNY-Binghamton, who gave me time and mechanical assistance, as well as advice and encouragement. My special thanks, too, to Bernard and Evelyn Rosenthal, Pat Wilcox, Burton Weber, Carl Dennis, Susan Strehle, William Spanos, my children Joel and Lucy Gardner, and my wife, Liz, all of whom read the manuscript in various stages and helped me see mistakesânot that there aren't still plenty.

Though based on and named for real places, the settings in this novel are essentially fictitious. I've moved things around (for instance the old Susquehanna depot restaurant and what locals call the Oakland block) to suit plot convenience. So far as I know there are no ghosts in Susque-hanna County, but looking at the place one feels there ought to be. If there are witches, I've never run into one.

The town of Susquehanna, Pennsylvania, fictionalized setting of most of this novel's action, is not, in real life, the dire, moribund place my story makes it, though at the time this story was set the town was endangered. It is a town that has more than once come close to extinction. In 1919, at the time of the great railroad strike in Susquehanna, the townspeople took the side of the striking railroad workers, fought the scabs and resisted the railroad executives, with the result that the railroad made a decision to abandon the town. The railroad then employed some two thousand Susquehanna workers and indirectly supported many more. When the railroad broke off all dealings with the town, Susquehanna staggered but somehow remained on its feet. It has similarly resisted more recent strokes of bad luck, mainly thanks to the town's pervasive sense of humor and stubborn independence, and the urgent concern with which people take care of one another. As of this writing the old railroad depot (which was not in fact demolished, though it was badly decayed) is being restored to its former grandeur by a local businessman, Mike Matis. It will be the last Victorian railroad hotel in America, and it was from the beginning one of the most grand and beautiful, an architectural wonder worthy to stand, as it does, not far from the immense and justly famous stone-hewn Starucca Viaduct. And a local park and dam project promises to free Susquehanna from dependence on outsiders for electricity. So this novel, insofar as it treats Susquehanna as a gloomy, dying place, is fiction, or fictionalized recent history. It tells of what might have happened and nearly did, but didn't. The old rusted sign mentioned in this storyâ

VACATION IN THE ENDLESS MOUNTAINS

âgives good advice. If any neighbor, having heard me say this, still feels ill-served, let him be angry at Peter Mickelsson, the “hero,” so to speak, of this novel. I've done my best with him, but the man's a lunatic. May he get his just deserts hereafter.

John Gardner (1933â1982) was a bestselling and award-winning novelist and essayist, and one of the twentieth century's most controversial literary authors. Gardner produced more than thirty works of fiction and nonfiction, consisting of novels, children's stories, literary criticism, and a book of poetry. His books, which include the celebrated novels

Grendel

,

The Sunlight Dialogues

, and

October Light

, are noted for their intellectual depth and penetrating insight into human nature.

Gardner was born in Batavia, New York. His father, a preacher and dairy farmer, and mother, an English teacher, both possessed a love of literature and often recited Shakespeare during his childhood. When he was eleven years old, Gardner was involved in a tractor accident that resulted in the death of his younger brother, Gilbert. He carried the guilt from this accident with him for the rest of his life, and would incorporate this theme into a number of his works, among them the short story “Redemption” (1977). After graduating from high school, Gardner earned his undergraduate degree from Washington University in St. Louis, and he married his first wife, Joan Louise Patterson, in 1953. He earned his Master's and Ph.D. in English from the University of Iowa in 1958, after which he entered into a career in academia that would last for the remainder of his life, including a period at Chico State College, where he taught writing to a young Raymond Carver.

Following the births of his son, Joel, in 1959 and daughter, Lucy, in 1962, Gardner published his first novel,

The Resurrection

(1966), followed by

The Wreckage of Agathon

(1970). It wasn't until the release of

Grendel

(1971), however, that Gardner's work began attracting significant attention. Critical praise for

Grendel

was universal and the book won Gardner a devoted following. His reputation as a preeminent figure in modern American literature was cemented upon the release of his

New York Times

bestselling novel

The Sunlight Dialogues

(1972). Throughout the 1970s, Gardner completed about two books per year, including

October Light

(1976), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the controversial

On Moral Fiction

(1978), in which he argued that “true art is by its nature moral” and criticized such contemporaries as John Updike and John Barth. Backlash over

On Moral Fiction

continued for years after the book's publication, though his subsequent books, including

Freddy's Book

(1980) and

Mickelsson's Ghosts

(1982), were largely praised by critics. He also wrote four successful children's books, among them

Dragon

,

Dragon and Other Tales

(1975), which was named Outstanding Book of the Year by the

New York Times

.

In 1980, Gardner married his second wife, a former student of his named Liz Rosenberg. The couple divorced in 1982, and that same year he became engaged to Susan Thornton, another former student. One week before they were to be married, Gardner died in a motorcycle crash in Pennsylvania. He was forty-nine years old.

A two-year-old Gardner, shown here, in 1935. He went by the nickname “Buddy” throughout his childhood.

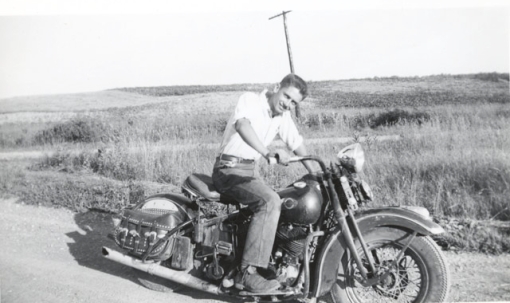

Gardner on a motorcycle in 1948, when he was about fifteen years old. He was a lifelong enthusiast of motorcycle and horseback riding, hobbies that resulted in multiple broken bones and other injuries throughout his life.

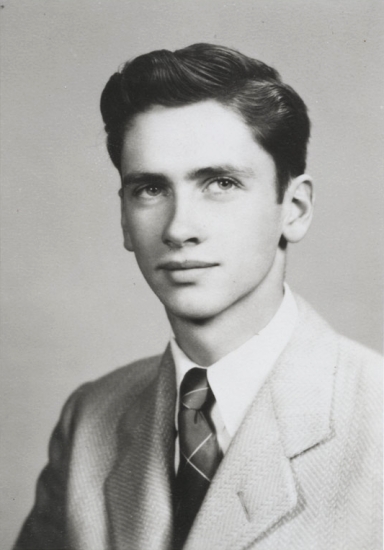

Gardner's senior photo from Batavia High School, taken in 1950. Though he found most of his classes boring, he particularly enjoyed chemistry. One day in class, Gardner and some friends disbursed a malodorous concoction through the school's ventilation system, causing the whole building to reek and classes to be dismissed early.

Gardner and Joan Patterson, his first wife, in the early 1950s. The couple were high school sweethearts and attended senior prom together in 1951.