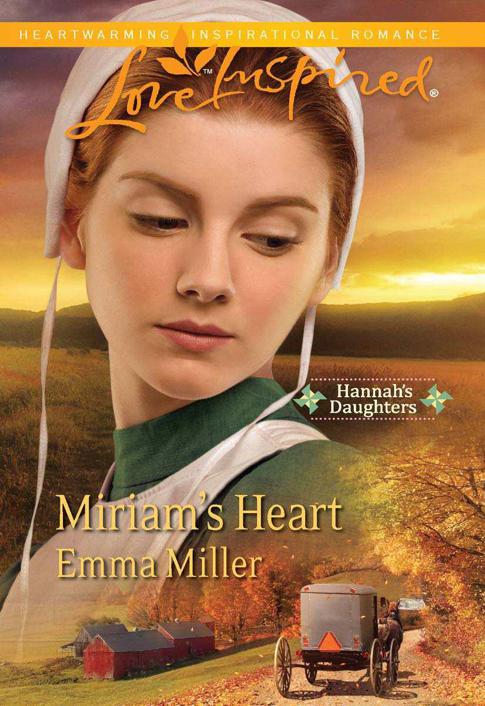

Miriam's Heart

Authors: Emma Miller

Charley offered his hand when she reached the top rung of the ladder. She took it and climbed up into the shadowy loft. Charley squeezed her fingers in his and she suddenly realized he was still holding her hand, or she was holding his; she wasn’t quite sure which it was.

She quickly tucked her hand behind her back and averted her gaze, as a small thrill of excitement passed through her.

“Miriam,” he began.

She backed toward the ladder. “I j-just wanted to see the hay,” she stammered, feeling all off-kilter. She didn’t know why, but she felt as if she needed to get away from Charley, as if she needed to catch her breath. “I’ve got things to do.”

Charley followed her down. Miriam felt her cheeks grow warm. She felt completely flustered and didn’t know why. She’d held Charley’s hand plenty of times before. What made this time different?

Charley was looking at Miriam strangely.

Something had changed between them in those few seconds up in the hayloft and Miriam wasn’t sure what.

lives quietly in her old farmhouse in rural Delaware amid fertile fields and lush woodlands. Fortunate enough to be born into a family of strong faith, she grew up on a dairy farm, surrounded by loving parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Emma was educated in local schools, and once taught in an Amish schoolhouse much like the one at Seven Poplars. When she’s not caring for her large family, reading and writing are her favorite pastimes.

Love comes from a pure heart and a

good conscience and a sincere faith.

—1

Timothy

1:5

For the lost Prince of Persia

and the blessings he has brought to our family

Kent County, Delaware—Early Autumn

“W

hoa, easy, Blackie!” Miriam cried as the black horse slipped and nearly fell. The iron-wheeled wagon swayed ominously. Blackie’s teammate, Molly, stood patiently until the gelding recovered his footing.

Miriam let out a sigh of relief as her racing pulse returned to normal. She’d been driving teams since she was six, but Blackie was young and had a lot to learn. Gripping the leathers firmly in her small hands, Miriam guided the horses along the muddy farm lane that ran between her family’s orchard and the creek. The bank on her right was steep, the water higher than normal due to heavy rain earlier in the week.

“Not far now,” she soothed. Thank the Lord for Molly. The dapple-gray mare might have been past her prime, but she could always be counted on to do her job without any fuss. The wagon was piled high with bales of hay, and Miriam didn’t want to lose any off the back.

Haying was one of the few tasks the Yoder girls and their mother hadn’t done on their farm since Dat’s death two years ago. Instead, they traded the use of pasture land with Uncle Reuben for his extra hay. He paid an English farmer to cut and bale the timothy and clover. All Miriam had to do was haul the sweet-smelling bales home. Today, she was in a hurry. The sky suggested there was more rain coming out of the west and she had to get the hay stacked in the barn before the skies opened up. Not that she minded. In fact, she liked this kind of work: the steady clip-clop of the horses’ hooves, the smell of the timothy, the feel of the reins in her hands.

If Mam and Dat had had sons instead of seven daughters, Miriam supposed she’d have been confined to working in the house and garden like most Amish girls. But she’d always been different, the girl people called a

tomboy,

and she preferred outside chores. Despite her modest dress and Amish

kapp,

Miriam loved being in the fields in any weather and had a real knack with livestock. It might have been sinful pride, but when it came to farming, she secretly considered herself a match for any young man in the county.

It had been her father who’d taught her all she knew about planting and harvesting and rotating the crops. Her earliest memory was of riding on his wide shoulders as he drove the cows into the barn for milking. Since his death, she’d tried to fill his shoes, but his absence had left a great hole in their family and in her heart.

Miriam’s mother had taken over the teaching position at the Seven Poplars Amish school and all of Miriam’s unmarried sisters pitched in on the farm. It wasn’t easy, but they managed to keep the large homestead going, tending the animals, planting and harvesting crops and helping the less fortunate. All too soon, Miriam knew it would be harder. With Ruth marrying in November and going to live in the new house she and Eli were building on the far end of the property, there would be one less pair of hands to help.

Blackie’s startled snort and laid back ears yanked Miriam from her daydreaming. “Easy, boy. What’s wrong?” She quickly scanned the lane she’d been following that ran along a small creek. There wasn’t anything to frighten him, nothing but a weathered black stick lying between the wagon ruts.

But the gelding didn’t settle down. Instead, he stiffened, let out a shrill whinny and reared up in the traces, as the muddy branch came alive, raised its head, hissed threateningly and slithered directly toward Blackie.

Snake!

Miriam shuddered as she came to her feet and fought to gain control of the terrified horses. She hated snakes. And this black snake was huge.

Blackie reared again, pawed the air and threw himself sideways, crashing into the mare and sending both animals and the hay wagon tumbling off the road and down the bank. A wagon wheel cracked and Miriam jumped free before she was caught in the tangle of thrashing horses, leather harnesses, wood and hay bales.

She landed in the road, nearly on top of the snake. Both horses were whinnying frantically, but for long seconds, Miriam lay sprawled in the mud, the wind knocked out of her. The black snake slithered across her wrist, making its escape and she squealed with disgust, and rolled away from it. Vaguely, she heard someone shouting her name, but all she could think of was her horses.

Charley Byler was halfway across the field from the Yoders’ barn when he saw the black horse rear up in its traces. He dropped his lunch pail and broke into a run as the team and wagon toppled off the side of the lane into the creek.

He was a fast runner. He usually won the races at community picnics and frolics, but he wasn’t fast enough to reach Miriam before she’d climbed up off the road and disappeared over the stream bank.

“Ne!”

he shouted. “Miriam, don’t!”

But she didn’t listen. Miriam—his dear Miriam—never listened to anything he said. Heart in his throat, Charley’s feet pounded the grass until, breathless, he reached the lane and half slid, half fell into the creek beside her. “Miriam!” He caught her shoulders and pulled her back from the kicking, flailing animals.

“Let me go! I have to—”

He caught her around the waist, surprised by how strong she was, especially for such a little thing. “Listen to me,” he pleaded. He knew how valuable the team was and how attached Miriam was to them, but he also knew how dangerous a frightened horse could be. His own brother had been killed by a yearling colt’s hoof when the boy was only eight years old. “Miriam, you can’t do it this way!”

Blackie, still kicking, had fallen on top of Molly. The mare’s eyes rolled back in her head so that only the whites showed. She thrashed and neighed pitifully in the muck, blood seeping from her neck and hindquarters to tint the creek water a sickening pink.

“You have to help me,” Miriam insisted. “Blackie will—”

At that instant, Charley’s boot slipped on the muddy bottom and they both went down into the waist-deep water.

To Charley’s surprise, Miriam—who never cried—burst into tears. He was helping her to her feet, when he heard the frantic barking of a dog. Irwin and his terrier appeared at the edge of the road.

“You all right?” Thirteen-year-old Irwin Beachy wasn’t family, but he acted like it since he’d come to live with the Yoders. He was home from school today, supposedly with a sore throat, but he was known to fib to get out of school. “What can I do?”

“I’m not hurt,”

Miriam answered, between sobs. “Run quick…to the chair shop. Use the phone to…to call Hartman’s. Tell them…tell them it’s an emergency. We need a vet right away.”

Miriam started to shiver. Her purple dress and white apron were soaked through, her

kapp

gone. Charley thought Miriam would be better off out of the water, but he knew better than to suggest it. She’d not leave these animals until they were out of the creek.

“You want me to climb down there?” Irwin asked. “Maybe we could unhook the—”

“We might do more harm than good.” Charley looked down at the horses; they were quieter now, wide-eyed with fear, but not struggling. “I’d rather have one of the Hartmans here before we try that.”

“The phone, Irwin!” Miriam cried. “Call the Hartmans.”

“Ask for Albert, if you can,” Charley called after the boy as he took off with the dog on his heels. “We need someone with experience.”

“Get whoever can come the fastest!” Miriam pulled loose from Charley and waded toward the horses. “Shh, shh,” she murmured. “Easy, now.”

The dapple-gray mare lay still, her head held at an awkward angle out of the water. Charley hoped that the old girl didn’t have a broken leg. The first time he’d ever used a cultivator was behind that mare. Miriam’s father had showed him how and he’d always been grateful to Jonas and to Molly for the lesson. Since Miriam seemed to be calming Blackie, Charley knelt down and supported the mare’s head.

Blood continued to seep from a long scrape on the horse’s neck. Charley supposed the wound would need sewing up, but it didn’t look like something that was fatal. Her hind legs were what worried him. If a bone was shattered, it would be the end of the road for the mare. Miriam was a wonder with horses, with most any animal really, but she couldn’t heal a broken bone in a horse’s leg. Some people tried that with expensive racehorses, but like all Amish, the Yoders didn’t carry insurance on their animals, or on anything else. Sending an old horse off to some fancy veterinary hospital was beyond what Miriam’s Mam or the church could afford. When horses in Seven Poplars broke a leg, they had to be put down.

Charley stroked the dapple-gray’s head. He felt so sorry for her, but he didn’t dare to try and get the horses out of the creek until he had more help. If one of them didn’t have broken bones yet, the fright of getting them free might cause it.

Charley glanced at Miriam. One of her red-gold braids had come unpinned and hung over her shoulder. He swallowed hard. He knew he shouldn’t be staring at her hair. That was for a husband to see in the privacy of their home. But he couldn’t look away. It was so beautiful in the sunlight, and the little curling hairs at the back of her neck gleamed with drops of creek water.

A warmth curled in his stomach and seeped up to make his chest so tight that it was hard to breathe. He’d known Miriam Yoder since they were both in leading strings. They’d napped together on a blanket in a corner of his mother’s garden, as babies. Then, when they’d gotten older, maybe three or four, they’d played on her porch, swinging on the bench swing and taking all the animals out of a Noah’s Ark her Dat had carved for her and lining them up, two by two.

He guessed that he’d loved Miriam as long as he could remember, but she’d been just Miriam, like one of his sisters, only tougher. Last spring, he’d bought her pie at the school fundraiser and they’d shared many a picnic lunch. He’d always liked Miriam and he’d never cared that she was different from most girls, never cared that she could pitch a baseball better than him or catch more fish in the pond. He’d teased her, ridden with her to group sings and played clapping games at the young people’s doings.

Miriam was as familiar to him as his own mother, but standing here in the creek without her

kapp,

her dress soaked and muddy, scowling at him, he felt like he didn’t know her at all. He could have told any of his pals that he loved Miriam Yoder, but he hadn’t realized what that meant…until this moment. Suddenly, the thought that she could have been hurt when the wagon turned over, that she could have been tangled in the lines and pulled under, or crushed by the horses, brought tears to his eyes.

“Miriam,” he said. His mouth felt dry. His tongue stuck to the roof of his mouth.

“Yes?” She turned those intense gray eyes from the horse back to him.

He suddenly felt foolish. He didn’t know what he was saying. He couldn’t tell her how he felt. They hadn’t ridden home from a frolic together more than three or four times. They hadn’t walked out together and she hadn’t invited him in when they’d gotten to her house and everyone else was asleep. They’d been friends, chums; they ran around with the same gang. He couldn’t just blurt out that he suddenly realized that he

loved

her. “Nothing. Never mind.”

She returned her attention to Blackie. “Shh, easy, easy,” she said, laying her cheek against his nose. “He’s quieting down. He can’t be hurt bad, don’t you think? But where’s all that blood coming from?” She leaned forward to touch the gelding’s right shoulder, and the animal squealed and started struggling against the harness again.

“Leave it,” Charley ordered, clamping a hand on her arm. “Wait for the vet. You could get hurt.”

“Ne,”

she argued, but it wasn’t a real protest. She didn’t struggle against his grip. She knew he was right.

He nodded. “Just keep doing what you were.” He held her arm a second longer than he needed to.

“Miriam!”

It was a woman’s voice, one of her sisters’, for sure. Charley released Miriam.

“Oh, Anna, come quick! Oh, it’s terrible.”

Charley glanced up. It was Miriam’s twin, a big girl, more than a head taller and three times as wide. No one could ever accuse Anna of not being Plain. She wasn’t ugly; she had nice eyes, but she couldn’t hold a candle to Miriam. Still, he liked Anna well enough. She had a good heart and she baked the best biscuits in Kent County, maybe the whole state.

“Don’t cry, Anna,” Miriam said. “You’ll set me to crying again.”

“How bad are they hurt?” Miriam’s older sister Ruth came to stand on the bank beside Anna. She was holding Miriam’s filthy white

kapp.

“Are you all right? Is she all right?” She glanced from Miriam to Charley.

“I’m fine,” Miriam assured her. “Just muddy. It’s Molly and Blackie I’m worried about.”

Fat tears rolled down Anna’s broad cheeks. “I’m glad Susanna’s not here,” she said. “I made her stay in the kitchen. She shouldn’t see this.”

“Did Irwin go to call the vet?” Charley asked. “We told him—”

“Ya.”

Anna wiped her face with her apron. “He ran fast. Took the shortcut across the fields.”

“Is there anything I can do?” Ruth called down. “Should I come—?”

“Ne,”

Miriam answered. “Watch for the vet. And send Irwin to the school to tell Mam as soon as he gets back.” The mare groaned pitifully, and Miriam glanced over at her. “She’ll be all right,” she said. “God willing, she will be all right.”

“I’ll pray for them,” Anna said. “That I can do.” She caught the corner of her apron and balled it in a big hand. “For the horses.”

Charley heard the dinner bell ringing from the Yoder farmhouse. “Maybe that’s Irwin,” he said to Miriam. “A good idea. We’ll need help to get the horses up.” The repeated sounding of the bell would signal the neighbors. Other Amish would come from the surrounding farms. There would be many strong hands to help with the animals, once it was considered safe to move them.

“There’s the Hartmans’ truck,” Ruth said. She waved, and Charley heard the engine. “I hope he doesn’t get stuck, trying to cross the field. The lane’s awfully muddy.”