Mission: Cook! (8 page)

Preheat

the oven to 350 degrees. Prepare the horseradish crust by mixing together the bread crumbs, herbs, horseradish, wasabi, 1 tablespoon of the olive oil, and the butter. Season to taste with salt and pepper. Set aside.

To make the braised endive, cut the endive in half and trim the core. Lightly sear the cut sides of the endive in olive oil over medium heat in an oven-safe nonstick pan. Sprinkle in the sugar, salt, pepper, and butterâcover and place in the oven, and continue to cook until softâ15 to 20 minutes. Use oven mitts to return the pan to the stovetop (the handle will be hot) and add the chicken

stock. (Leave the oven on for the salmon.) Reduce the cooking liquid to a syrup and, if needed, season with salt and pepper.

To make the beet reduction, sauté the carrots, onions, and celery in the olive oil until brown. Add the thyme halfway through the process. Add the port and red wine, and reduce to a syrup. Then add the beet juice and reduce to a syrup. Strain and set aside.

Have a baking sheet ready. Season the salmon with salt and pepper. Heat the remaining 2 tablespoons olive oil in a pan and sear both sides of the salmon over high heat. Transfer the salmon to the baking sheet and press a horseradish crust into the surface of each piece. Bake the salmon until done, 5 to 7 minutes, but do not overcook. The fish is done when it springs back upon being lightly prodded. (Because of “carryover” cooking, the fish will continue to cook even after it is removed from the oven.)

Toss the raw endive and frisée with the lemon juice, olive oil, and salt and pepper. Reheat the beet reduction, remove from the heat, and whisk in the butter. Season with salt and pepper.

PRESENTATION

Place 2 halves of a braised endive on each plate and top with the cooked salmon. Drizzle the beet reduction around the salmon. Top the cooked salmon with the greens and serve.

A Note on Mirepoix

In French cooking, a mirepoix is used as the basis of flavor in many dishes. Classically, it is celery, carrots, and onions sautéed in butter to bring out their sweetness. In the beet reduction, we are cooking it in olive oil instead.

L

ET YOUR CREATIVITY BE YOUR GUIDE. AS A PROFESSIONAL, I HAVE A PER

sonal conceit that I never do the same dish twice. However, in thinking about it, I realize that no one ever cooks the same dish twice.

Even if you have made the same dish a thousand times, even if you follow your favorite recipe down to the minutest detail, you will never cook with the same carrot, the same onion, the same sprigs of thyme, the same splash of wine, the same cut of beef or fish, even the same spoonful of sugar or honey or flour. An experienced gardener will tell you that no crop of herbs, fruits, or vegetables is the same as the one from the year before. Variations in climate, rain, soil amendments, the weather on the day you harvest the crop, as well as the time of year you harvest, all have an impact. If the ingredients are different, how can the meal be the same? Be mindful of the ingredients in front of you; make sure they are fresh and beautiful, be attentive to their quality, be expressive in the way you prepare and combine their flavors.

Be the food.

Let the food in front of you speak to you and inspire you. Really

look

at your family and friends when they are eating your food. Examine your own palate and thoughts and feelings when you eat. Most of all,

enjoy

your food. Do your best to make sure that whatever you make is a pleasure to eat. There are few higher callings.

SUNDAY ROASTS AND THE WHITE RABBIT

Charming stories of Sunday dinner and a meeting with a surprise culinary character whilst out at sea

Robert Irvine in the Sea Cadets, tallest in back row, third from right

F

OOD IS A PRISM THROUGH WHICH I VIEW THE WORLD, AND THE WORLD

reflects its light back into my cuisine. When I travel, when I meet new people, when I take on a new position or challenge, when I read a book or hear a song, when I speak to other chefs and taste their food and see their approaches, when I eat something new and am impressed or depressed about it, these experiences influence, however profoundly or subtly, the very next dish I make.

Like many a cook before me, my earliest influences and attitudes about food came at my mother's knee. I grew up in working-class Salisbury, in Wiltshire, England, with my mom and dad, older brother, Gary, and younger sisters,

Colleen and Jackie, in a town that boasts the tallest cathedral spire in the country and is just a stone's throw from Stonehenge. I always thought my mother was the most beautiful woman in the world, with her long, dark hair and olive skin, like Sophia Loren. My dad, a former professional soccer player, had brown wavy hair and the hallmark leanness and keenness of a former athlete, and he was always the very expression of the staunch and steadfast Belfast Irishman. He earned his living as a painter, of houses and rooms, and my mother worked in a wallpaper shop, so between the two of them, they had us pretty “well covered.”

You could say that I grew up before the Revolution. In the England of the late sixties and early seventies, there was no Food TV, no celebrity chef culture, no fascination with cookbooks or kitchen experimentation, and no gourmet food stores, and regular folks seldom ventured out of the house for dinner. This fact is easily borne out by the general and worldwide sneering opinion of the phrase “English cuisine,” which has persisted up until just the last few years.

My mother, Patricia, was a typical English cook. That meant that in the span of a week, we usually ate lots of tinned and processed foods, our mains were inevitably indifferently cooked, and starches were plentiful but invariably bland unless smothered with salt or butter or English mustard. Fat was welcome; bright green color on a plate was not. Desserts were sweet puddings. I often subsisted from day to day, once I stood tall enough to reach the icebox, on boxes of cereal drowned in gallons of milk. Fresh was an adjective seldom applied to ingredients in our house. Special attention was reserved for anything that resembled or was reputed to be a vegetable. These were boiled mercilessly until pulverized, and with extreme prejudice.

But my mother was a born roaster.

Whether she chose to roast a chicken, a joint of beef, a goose, or a whole turkey, it was always

delicious.

The aromas would permeate and anoint the household as anticipation built toward the climax of its presentation at the table. The skin was crispy and perfect, the flesh tender and succulent, juicy, and bursting with flavor.

Robert as a young boy

Therein lay the redemption of the typical British cook.

I remember participating in the preparation of Sunday dinner at about age ten. Our kitchen at that time was simple, neatly tiled, small but comfy and functional. In fact, the ancient Aga range was the source of most of the heat in the house, which was not all that unusual in our neighborhood then. I can remember often scrambling out of my room in winter through utterly chilly hallways to the crispy, comforting warmth provided by that oven. My mother would dry the washing on a line by the range, and it was her practice to heat water on the stovetop for the children's baths when we were all small enough to be scrubbed in a big tin washtub on the kitchen floor.

I would help my mother “prep,” often with my sisters, dressing the roast the night before. Mom would rise early Sunday morning and put it in the oven. The scents would make their way through the house, greeting me when I rolled out of my bed. My father, Patrick, would nearly always leave to play a round of golf. I would busy myself tending to the grass in the garden, or playing soccer with my friends.

The man of the house would arrive back at home at exactly 2:30, and dinner would be on the table. Mom would usually serve three or four different kinds of potatoes with dinner. My dad has an Irishman's fascination with every kind of potato imaginable. My mother's roasted potatoes were delectable and memorable. She would parboil them first, then roast them to a faultless golden brown, salty and crunchy on the outside, moist and soft on the inside. Sides would include mashed carrots or peas, Brussels sprouts, turnips, or parsnips, cooked to death. You had to eat them to get to your dessert, and the price was well worth paying. Treacle custard, spotted dick, or steamed pudding might be on the menu, all excellent.

Mom plated each of our dinners and served us individually. Our plates were piled high and we feasted. Those meals remain some of the most satisfying in my memory. I was a kid who ate as much good food as I could get my hands on, but I always left room for dessert. On that score, I usually managed to grab my father's dessert as well. The man simply overestimated his capacity for potatoes and ran out of room.

T

HE SUNDAY DINNER IN ENGLAND IS MORE THAN JUST FOOD; IT'S A TIME

when families sit and dine together. It's the end of the week, and the whole

dinner turns into a ceremony. It is the weekly celebration of an Englishman's house as his castle. Sunday dinner means as much to an Englishman as does Mass to a Catholic.

A great Sunday lunch might consist of an appetizer, like shrimp cocktail, followed by roast beef and yorkshire pudding, and normally finish with a dessert like a banana bread and butter pudding.

Here is one way to create a fabulous “English-style” Sunday dinner.

SERVES 6

FOR THE ROAST

6 pounds sirloin roast (top round or bottom round will do as well; make sure the meat has some fat on it, which will help with self-basting)

2 tablespoons flour

2 tablespoons stone-ground mustard

¼ cup canola oil or grapeseed oil

Sea salt or kosher salt

Freshly ground black pepper

2 carrots, washed but not peeled, roughly chopped

2 medium onions, peeled and roughly chopped

2 celery stalks, washed and roughly chopped

4 bay leaves

FOR THE YORKSHIRE PUDDING

1 cup all-purpose flour

¼ teaspoon salt

2 medium eggs

1 pint whole milk

Canola oil

Freshly ground black pepper

The

first thing you need to do is preheat the oven to 425 degrees.

Wash the beef to remove any unwanted smells, and pat it dry with paper towels.

Mix the flour, mustard, and oil together, and coat the beef with the mixture. Season with salt and pepper pretty heavily, which helps the flavor when cooking.

In a roasting pan, place the chopped carrots, onions, celery, and bay leaves, then sit the beef on top of the chopped vegetables.

Place the pan in the preheated oven and cook for the first 20 minutes at 425 degrees, then reduce the temperature to 325 degrees until the roast is cooked. (A good rule of thumb is to cook the meat for 10 to 15 minutes per pound. When using a meat thermometerâwhich every cook should haveâthe internal temperature should be 115 degrees.)

When the roast is cooked to your liking, remove it from the roasting pan and let it rest for 20 to 30 minutes under tented aluminum foil prior to carving. Make sure you reserve the juices for the gravy later, and remove the bay leaf.

Once the roast is in, it's time to make the Yorkshire pudding:

To make the Yorkshire pudding, sift the flour and salt into a bowl, add the eggs, and then slowly incorporate the milk, being careful to add the milk slowly, as each batch of flour is different and some flour may absorb more milk than others. (You want the mixture to be smooth, but not runny.) Whisk into a smooth batter and let rest for 30 minutes in the refrigerator.

Take a muffin tin and place some oil in each mold (about ¼ inch in each); place the tin in the oven for 2 to 3 minutes until the oil smokes. Add the batter into each mold (two-thirds to three-quarters full) and return to the 325-degree oven to cook for 15 to 20 minutes until they have risen and are golden brown. You want them to be hard when you remove them from the oven.

The Sunday roast is often accompanied by roasted or mashed potatoes and any number of side dishes. The following are a couple of my favorites.

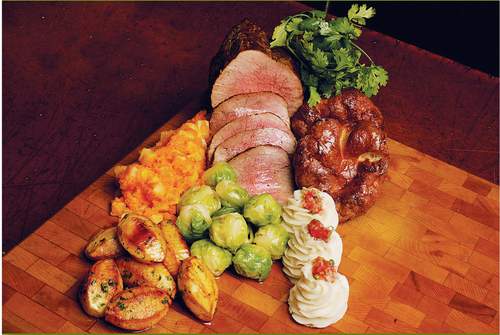

Sunday Roast Dinner

(clockwise from lower left):

Hassleback Potatoes, Carrots and Rutabaga, Roast Beef, and Yorkshire Pudding, served with mashed potatoes and Brussels sprouts

SERVES 6

1 cup mayonnaise

½ cup tomato ketchup

Juice of 1 lemon

1 pound small cooked shrimp (larger shrimp can be used, if you prefer)

Salt and pepper

1

/

8

cup brandy (optional)

1 head iceberg lettuce, finely shredded

1 red onion, finely diced

2 large tomatoes (insides removed), diced

2 hard-boiled eggs, chopped

2 tablespoons chopped chives or parsley, for garnish

Cayenne pepper

With most shrimp cocktails, one suffers a letdown when all the shrimp is eaten. Not so with this one. By the time the shrimp is gone, the dressing has had a chance to trickle down into the serving glass to infuse the remaining ingredients with its flavor, now enhanced with a fresh seafood essence by having coated the shrimp. This is a savory treat from top to bottom.

Mix

together the mayonnaise, ketchup, and lemon juice. Add the shrimp and adjust the seasoning with salt and pepper as needed (be careful with the salt; there's already some in the ketchup and mayonnaise). If you choose, add the brandy at this time. Set aside in the refrigerator.

Using a stemmed wineglass, place enough lettuce in the glass to fill it halfway, then add the red onion, tomatoes, and chopped eggs.

Take the prepared shrimp mixture and cover the lettuce in the glass; sprinkle with chopped parsley or chives and cayenne.

Serve with a crisp white wine, a Pinot Grigio or something not too sweet.

SERVES 6

2 pounds medium potatoes (your choice of type)

1½ tablespoons flour

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

1

/

3

cup grapeseed oil

¼ cup very finely chopped herbs (sage, parsley, or tarragon)

Since my father is Irish, my mother would always make extra potatoes because he loved them. This recipe can be halved, if you want.