Modern Homebrew Recipes (51 page)

Read Modern Homebrew Recipes Online

Authors: Gordon Strong

Tags: #Cooking, #Beverages, #Beer, #Technology & Engineering, #Food Science, #CKB007000 Cooking / Beverages / Beer

Boil length:

90 minutes

Final volume:

6.5 gallons (25 L)

Fermentation temp:

Start at 68°F (20°C) and let rise to 72°F (22°C) after 4 days.

Sensory description:

The beer is highly attenuated and yeast-driven. Most flavors are fairly moderate. The hops can have an iron-like quality to them, and the grain can be coarse or grainy. The high carbonation and attenuation makes this a thirst-quenching beer. It shouldn’t have a caramel flavor (if it does, it’s likely from oxidation).

Formulation notes:

You pretty much need the Australian yeast for this; it’s so attenuated that other yeasts won’t really taste right. I use a blend of base malts to give it a bit of grainy coarseness while still having bready and doughy flavors. I can’t easily get Australian malts, so I’m blending a variety of other base malts to get a similar flavor. Sugar helps with attenuation, and a hint of color malt makes it a nice deep gold color (not sure if it’s traditional, but it’s the way I choose to adjust the color without adding flavor). Be sure to carbonate it highly; it’s an important part of the style.

Variations:

If you don’t like the Pride of Ringwood hops, you can use a mix of Galaxy and Cascade, two Australian favorites, or possibly come up with a combination of New Zealand hops. If you can get Australian base malt, that would be even better, but I try a blend of base malts to give additional complexity.

Also known by its Germanized name,

Grätzer,

this style is unusual in that it is a low-gravity wheat beer that uses special oak-smoked wheat malt. Until recently, if you wanted to make this style you had to smoke your own malt. However, Weyermann came out with special malt just for this style—

Weizenrauchmalz®

. I want to thank William Shawn Scott for helping me with the BJCP Style Guidelines for this style; he also provided some helpful recipe tips based on Polish brewing records.

Style:

Historical Beer (New BJCP Style, Grodziskie)

Description:

A low-gravity, light-bodied, pale, clear, highly-carbonated wheat beer featuring high bitterness and oak-smoked malt. A traditional beer style from Poland that died out but is now enjoying renewed interest.

Batch Size: | OG: | FG: | |

Efficiency: | ABV: | IBU: | SRM: |

Ingredients:

7.75 lb (3.5 kg) | Oak-smoked wheat malt (Weyermann) | Mash |

1 lb (454 g) | Rice hulls | Vorlauf |

2.25 oz (64 g) | Polish Lublin 3.5% pellets | @ 75 |

0.75 oz (21 g) | Polish Lublin 3.5% pellets | @ 30 |

Wyeast 2565 German Ale/Kölsch yeast |

Water treatment:

RO water treated with ¼ tsp 10% phosphoric acid per 5 gallons

1 tsp CaSO

4

in mash

Mash technique:

Step mash, mashout, add rice hulls at mashout and allow to settle to aid lautering

Mash rests:

104°F (40°C) 35 minutes

125°F (52°C) 40 minutes

Ramp up slowly using direct heat and recirculation, taking at least 20 minutes

158°F (70°C) 30 minutes

170°F (77°C) 15 minutes

Kettle volume:

8.5 gallons (32 L)

Boil length:

90 minutes

Final volume:

6.5 gallons (25 L)

Fermentation temp:

62°F (17°C)

Sensory description:

Kind of similar to a Berliner Weisse, except that instead of being sour, it’s smoky and bitter. Both are highly carbonated, pale, clear, low-gravity beers. The oak smoke has a drier, leaner, more mellow character than the typical beechwood smoke. The beer itself is very clean, and should never, be sour.

Formulation notes:

You absolutely cannot substitute the Weyermann

weizenrauchmalz

. Their normal beechwood-smoked barley malt does not have the same profile; it is sharper, more intensely smoky, and often has a ham-like quality. However, the hops make up for the lower smokiness in this beer. Use Polish hops if you can find them, otherwise good-quality Czech or German hops. Use Biofine clear or another fining agent to clarify the beer; it should be brilliantly clear like a

Kölsch.

Carbonation should be very high.

Variations:

This already uses some substitutions, but if you can find the original

Grätzer

yeast, use it. It’s interesting in that it has a soft, red apple ester that is very unusual. But

Kölsch

yeast is a good stand-in. You can adjust the bitterness level and gravity to your taste. You can also add some Pilsner malt to the grist if the smoke is too much for you. Later year versions of this style were stronger and not as bitter, but try it’s worth trying the version that was popular in its heyday.

1

http://www.sphbc.org/mwhboy/signature-recipes/curt-stock-s-craptastic-cream-ale

Although I use recipe software for most of my brewing calculations, sometimes I run them by hand to make a quick adjustment or double-check a result that looks dodgy. Here are the ten most common calculations that I use:

1. Estimating your target final boil volume

– Your final boil volume needs to be large enough to account for the various places in transfer and fermentation where some beer gets left behind. To properly estimate the final boil volume, measure how much waste you have on your system (hop mass, trub, kettle waste, etc.). Now measure the usable volume of beer you have and compare that against your actual final boil volume. The difference is the overall waste of the batch. Make sure to adjust your batch size based on the final boil volume, not the final volume in the fermenter. Also remember that the waste will vary depending on how many hops you use, or if you have excessive break.

It can be useful to record the volumes of your wort or beer at several points in the process: pre-boil volume, post-boil volume, volume transferred to fermenter, and finished beer volume available for packaging. The post-boil volume is your batch size, and should be used as a basis in your calculations.

On my system, I find that if I have between 6.25 gallons and 6.5 gallons at the end of the boil, then I’ll have plenty of beer to fill a 5-gallon keg. I shoot for 6.5 gallons at the end of the boil, transfer about 5.5 gallons to the fermenter (I use 6.5 gallon fermenters), and then ultimately rack 5 to 5.25 gallons from the fermenter for packaging. If I have more than will fit in a keg, I

store it in a 2 L plastic bottle so I can watch the progress of the conditioning and maturation tapping into the keg.

This seems like a lot of loss (1.25 gallons), but I always rack the clearest portions of wort and beer. I’m trading volume for quality without having to perform additional steps to recover more usable beer. That’s a tradeoff some homebrewers can make, but you won’t see it in commercial operations. Understanding your losses lets you scale your batches accordingly to hit your desired final volume for packaging.

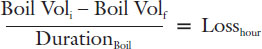

2. Calculating evaporation rate

– Take the difference between your starting volume (Boil Voli) and your ending volume (Boil Volf) and divide by the boil length (DurationBoil):

This will tell you how much volume evaporates per hour. If you want to calculate it as a percent, take the number of gallons lost per hour and divide it into your starting volume. This rate can vary based on environmental conditions (altitude, humidity, temperature, wind, etc.), but you should have a baseline for your system.

For an average boil on my system, I start with 8.5 gallons, boil 90 minutes, and wind up with 6.5 gallons. I lose 2 gallons (8.5 – 6.5 = 2) in 90 minutes (1.5 hours), or 1.3 gallons per hour. Expressed as a percent, that’s 15.3% (1.3 / 8.5) lost per hour. I lose the same 2 gallons in 90 minutes whether I’m making a 5-gallon batch or a 10 gallon batch, since I have the same surface area exposed and I’m maintaining a similar strength boil.

If you have a constant loss rate for different batch sizes, adjust the evaporation rate in your brewing software. For example, in 90 minutes I boil 13.5 gallons down to 11.5 gallons, so I’m still losing = 2 gallons (13.5 – 11.5) in 1.5 hours, or 1.3 gallons per hour. Despite the same overall volume loss, my evaporation rate percent is now 9.6% (1.3/13.5).

My recommendation for homebrewers is to understand how much volume you lose for your various boil lengths, and then

adjust your starting volume to hit your target volume based. This is not a figure that should be the same for every brewer; it will be dependent on your particular system.

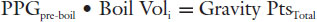

3. Estimating post-boil gravity

– First, understand that the total gravity points

1

in your kettle are a constant, regardless of the amount of water. Before the boil starts, measure your specific gravity (SG, converted into points per gallon – PPG

pre-boil

) and wort volume Boil Voli) to get a total gravity measurement (Gravity Pts

Total

):

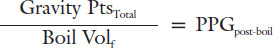

Even if water boils off, your wort will still have the same gravity points. To get post-boil gravity (

PPG

post-boil

), divide by the post-boil volume (

Boil Vol

f

):

If you are trying to hit a certain gravity and volume target, you may need to adjust the length of boil, or add water or additional fermentables.

For example, if you fill your kettle with 8 gallons of 1.042 wort, you have 42 points per gallon (PPG) of extract, or a total gravity of 336 (42 • 8).

Those 336 points of extract will remain constant throughout the boil. If you subsequently boil down to a final volume of 6.5 gallons, you will have 51.7 (336/6.5) points per gallon of extract. This equates to a specific gravity of 1.052. The trick is to drop the leading 1 from a gravity reading and use the decimal fraction as the points per gallon number. If you were using a brewing calculator, you could enter the formula as: