Mr Darwin's Gardener (7 page)

Read Mr Darwin's Gardener Online

Authors: Kristina Carlson

Caw-caw-snow, the crow caws.

And the jackdaws take wing from the steeple to bear witness:

It has snowed during the night.

The roofs of the houses are white and the

chimney-cowls

wear white hats.

White gauze sticks to the meadows and hedges. In the ploughed field, snow has painted every other furrow white.

A pallid sun glows through cloud.

Â

Cathy Davies draws small squares for houses. She adds a bigger square for Mr Darwin's house, and a rectangle for the church, topped by a cross; then roads and paths leading from house to house; and, on the roads, small people running hither and thither on stick legs.

John presses a sooty forefinger to the paper and asks: Where am I?

Cathy draws two small figures and a line below them: a sledge. She wants to pull John to school on the sledge.

Thomas sweeps the steps. Dry, light snow rises up in a cloud. Crystals glitter. Blades of grass are dimly visible through the snow on the lawn. He puts the temperature

at two or three degrees below freezing. A cold, metallic smell fills the air. Breath billows. Smoke from the village chimneys rises in dense columns towards the sky.

Let the children pull the sledge over the stiff, frosty grass. Even though it will get stuck on the road, Cathy, tenacious as a plough-horse, will drag the sledge to the school.

Â

The road is a white corridor between the hedges. The wind and footsteps cause a flurry of flakes. Nobody else has walked here. No traces in the garden either; no footprints left by Mr Darwin, no traces of his stick. He is old now and ailing, but he rarely misses his morning walk.

Mr Darwin is the only person in the village not to have read about Daniel Lewis's article, Thomas thinks. That is because a spacious mind engages with big questions, whereas small souls are satisfied with crumbs to chew on. Thomas opens and closes the greenhouse door. As warm air hits the glass, a crust of ice condenses on the outsides of the panes. On the inside, drops of moisture form on the windows. The air is thick with the smell of water, earth and plants. He takes down a notebook from a hook on the wall. The book holds the names of plants, along with the associated instructions and timetables. Mr Darwin himself wrote them.

The genera of the families Agavaceae, Cactaceae, Crassulaceae and Aizoaceae, and the genus

Angraecum

, are strange and off-putting, like foreigners whose

language

Thomas cannot understand. One can only serve them, whereas more mundane plants can be commanded, directed, divided, cut, pruned, grafted, trained.

He has to arrange, bag and catalogue the seeds collected in autumn; also clean the pots that Mrs Darwin wants on the windowsills in spring. Then begonias, geraniums

and fuchsias will be carried out of the cellar where they spent the winter.

Thomas lifts a box off the shelf. It contains the bags that are ready, arranged in alphabetical order.

Aquilegia bertolonii

, written in my handwriting. The black aquilegia seeds are smaller than a full stop on a piece of paper. In nature, they spread well by themselves. All these seeds have been collected for storing. There may be a gardener in some corner of the earth who needs this particular common variety.

I could measure the test area in the snowy field today.

Â

Waiting, waiting. In the waiting room are waiting: the chimney sweep's little finger, Edwin's knee, Sarah

Hamilton's

God-knows-what. Someone is always waiting. Robert Kenny is hard pressed to hold his own head upright between his shoulders.

Mary clears her throat behind the door. It is her fault I have the odd nip, and another one. I down spirits for professional purposes. It does not smell. I medicate myself since I was unable to cure Eleanor. I will not recover, I get drunk. Intoxicated, a man does not remember if he is well or ill. So what should be bad is actually good. I recommend a nip to all my patients.

I also recommend prayer.

Hear us, almighty and most merciful God and Saviour; extend thy accustomed goodness to this thy servant, who is grieved with sickness.

If that does not work, at least the doctor is not to blame.

Come in. Yes, you, chimney sweep. What narrow flue was it that caused you to break your finger? All right, all right, Miss Hamilton. Patience, your flue will be scrubbed forthwith!

Oh, oh, Advent.

Waiting makes for a rush. There is hardly a moment to draw breath and one has to sweep snow off the steps, heat the house, do the laundry, starch, iron, darn, sweep, wax, polish, dust, air, boil, crush, whisk, knead, roll, roast, ice, sew, go out for sugar, salt, flour, currants, cinnamon, almonds, soda, buttons, ribbons, candles; run to the shop and back, to the neighbour's, the church, the chicken coop, the shed, and back into the kitchen before a burning smell comes from the oven.

O Sapientia

, Sarah Hamilton sighs, though the coming Sunday is only the second of Advent.

O Sapientia

is sung eight days before Christmas, but Sarah just cannot wait. She busies herself round the house â like a tea cosy on wheels, Hannah Hamilton thinks, peering over her glasses.

She looks down again, applying stem stitches to linen. She uses green thread to create leaf skeletons. She employs satin stitches for the leaf blades and bird's-eye stitches in red for flowers.

So we waited last year, too, and the year before, and the one before that. The candles were lit in the wreath, first one, then another. Every year, we ascend to Christmas. But once we have reached the summit, the sickening descent

begins, as early as Epiphany. When the body is made to fast, and the soul too suffers, you fall more swiftly.

Sarah has been waiting for a man, a miracle, Christmas, spring. She has been waiting. Pity that both French and Latin will end up as food for worms.

Not yet, no.

Hannah breaks the thread with her eye tooth. I'll go first.

Though Death's records do not follow the human calendar, I want to see Sarah at my graveside in elegant new mourning clothes. She will lower a bouquet, wiping the corner of her eye with the handkerchief I embroidered with her initials the Christmas before last. She will incline her head to the vicar. Grief bestows dignity on some, making them a head taller. It will suit Sarah. Thomas Davies is another matter.

Eileen Faine and Alice Faine turn into the yard from the road. Sarah flutters among the curtains, gets caught up in a silk tassel. She flies to the kitchen, the door, the window, where she straightens a curtain. Rosemary Rowe and Jennifer Kenny come in too.

Must warm the teapot.

Â

The do-gooders sit in the Hamiltons' living room. Alice is embroidering a watch case, Sarah a pair of slippers, Rosemary a child's bonnet.

Eileen Faine stretches her arms out and screws up her eyes, trying to thread the purple silk. She misses, misses. She wets the end of the thread with the tip of her tongue. A miss, a miss. At last, a hit. The thread tautens. She is embroidering a scissor case to be sold at the church bazaar: a pattern of Sarah's with flowers and parrots.

It's all right, all right. Miserable, Eileen stabs the needle into the fabric. When I embroidered a pair of hunter's

slippers, I bought them myself, since nobody else wanted them. It makes no difference whose purse you get the money from. It goes to a good cause, not the verger's pocket. But I would rather donate my goodness in the form of cash. The threads are getting knotted on the reverse. This poor-quality velvet from Rowe's is coming apart. No, money is not all right. Money smells of arrogance, whereas a generous mind is embroidered on to a scissor case, stitch by stitch.

Â

It is not safe to open one's mouth in company, not when pain can make anything spring from one's lips. Rosemary is silent. She twists the thread in her fingers. The white thread darkens, though she scrubbed her hands and nails after emptying drawers of postcards, glass baubles and snuffboxes.

They

will no doubt want to talk about what cannot be talked about: Margaret, who left and has not been heard of since. I think of her and I tell God: Do not get angry, I would like to meet Margaret and the child, if it exists, though the whole village knows who the father is. Stuart Wilkes said to Harry: That man is the scion of a monkey. Whatever Daniel Lewis may be, he is not a monkey, exactly; and even if he were, I would love the child as I love Margaret.

Fabric and needle and cotton fall to the floor.

Â

Sarah clears her throat, and reads aloud from chapter fifteen of the Epistle to the Romans:

We then that are strong ought to bear the infirmities of the weak, and not to please ourselves.

Jennifer Kenny drinks tepid tea. She folds a flannel shawl on the table and picks up a square piece of fabric,

ready-cut, from a pile. She threads the cotton and hems the material with blanket stitches. She says: Piety and Charity are drawn from the same well.

She does not say that St Paul is dull and self-satisfied, like a lot of men. She does not say that water stagnates in the village well, because it has been contaminated by Tedium. Hypocrisy, Narrow-Mindedness and Self-Righteousness teem there like tadpoles in a pond. She does not say that all of creation is obliged to change and develop, albeit slowly, for if God had put everything firmly in place six thousand years ago, it would be depressing to look even a year into the future.

Hundreds and thousands of people suffer hunger, poverty, disease, madness and disability. Beneficence demands a grateful smile from them and then shuts them out, to rest its head on the pillow at night, satisfied that good has been done. Human misery finds no room in a piety that tots up the sins of drunkenness, fornication, theft and mendacity, and calculates poverty and sickness as the result.

The poor will not thank a do-gooder who merely tramples them deeper into the mud. They would rather throw a rotten turnip at her back, that is, if they have a turnip. That is what happened to me in Fox's yard. I had applied cream to the old woman's bedsores and cleaned the old man's ears. In her powerlessness, the daughter raised her hand and threw.

Â

The horse is on its arse and the cart on its side!

Rowe's little maid, Ginger, is on the steps, shouting. Sarah, in the middle of reading the Bible, is startled by the banging on the door. She goes to open it.

The master told the mistress to come!

Rosemary Rowe shoves embroidery frame, needles, thread into her sewing bag. She barely has time to say thank you and bow. She runs along the village street to the shop. Eileen Faine, Alice Faine and even Jennifer Kenny catch her haste.

They're running like chickens, Sarah says at the window.

Without the wheelchair, I'd run too, Hannah replies.

Â

One of the cart's shafts is hanging loose, dislocated, but the horse's arse is where it should be, and the cart is standing on its wheels. Harrison, the driver, is hopping on one leg, though.

The horse flattens its ears.

Harry Rowe slams the door to the storage room shut and turns the key in the padlock. The merchandise takes off if you turn your back. The brats are on the scene first and then the rest. A moment ago there was not a single customer in the shop, and both yard and road were empty. They sprang up out of nowhere like mushrooms.

Henry Faine points his stick at a snow-covered hole.

Harry Rowe puts the key in his pocket. There's the master of the Hall, analysing the course of events, but I was the only one who saw what happened. The horse lurched, but did not fall. The cart slipped, though, and a shaft broke. Harrison had jumped off his seat and then a wheel rolled over his foot. A real party here, with fresh dung buns on offer. I wish Rosemary would look at Harrison's foot, but no, the first-aid team has arrived: Jennifer Kenny. What is holding up the doctor? I do not know but I can guess.

Overreaction, Eileen says. Rosemary Rowe twists her hands.

The climax is over, but the audience is reluctant to disperse.

Harrison gets a fright when Harry Rowe clasps his arm: Let's go. What if he's in for a beating, for blundering? But that's not it. In the shop, Jennifer Kenny takes off his boot and sock and examines the foot, which smells worse than it looks. She washes the foot, smears it with liniment, wraps it in a bandage.

People stroll round the horse and the cart in the yard. The whole incident has died down. That is, unless

Harrison's

foot has been pulped. Who'll pay the doctor's fees, and the compensation if he can't walk or do his job? asks Sarah Hamilton, who has also made it to the shop now. But no, not even a broken bone.

Â

Mr Hume claims that in country places, a rumour about a marriage will take flight more easily than any other. But he is wrong there, for accidents and diseases excite people far more. The joy of being able to impart such engrossing news, and be the first to spread it, is much greater.

It was snowing. In the mornings, the chickens scratched at the white ground. Then Harrison overturned his cart in Rowe's backyard. And now this! Martha Bailey dusts and cleans shelves. She arranges glasses. Robert Kenny is drunk in the middle of the day. It isn't the first time, but it is Advent now, and you would expect people to mend their ways in anticipation of the Lord.

I carry full tankards to Kenny and Wilkes's table.

Business

is business, every penny counts.

Only if a woman has property or a pension can she afford to sit and embroider for charity. I wonder what Rosemary is doing in those circles. I was not invited.

Jennifer Kenny earns her keep. She is a nurse, and quite different from her nephew. The sick will always be with us. Only funeral directors have a steadier income. But a burial affects an individual just once, whereas a thirst for beer endures as long as the liver and other internal organs hold up. If a man drinks at the Anchor for ten or twenty years, James and I have a better income per customer than the funeral director.

Â

Electricity, says Stuart Wilkes. Robert Kenny nods away. Consensus is a tepid brew, like beer, and it makes you feel better. The future's in electricity, Stuart says. Robert nods.

Machines that run on muscle power require human effort. But electricity moves cogs invisibly. You press a switch and there is light, though this village has not witnessed that yet.

The shoelaces and funnel are nothing but tinkering, Stuart thinks. They are pastimes I took up when I was sent home from school for six months to calm down. There was an explosion in the classroom and Edward Sales's eyebrows were singed. The headmaster smiled down at me condescendingly. All those men at university who thought themselves better than I, more talented, smiled the same way, puffing themselves up. I could not stand them. I could not even bear to walk on the same side of the avenue as them. When they smiled, their eyebrows rose like caterpillars towards the domes of their heads. They must be completely bald now, but I have hair on my head. They are professors, members of the Royal Society, sour gentlemen who flap around in their black gowns, with brains so dry they rustle.

What is there to envy?

Your actions must be proportionate to your talents, the headmaster said. He adjusted the position of the spectacles on his long nose. I thought: Your education is a fart that comes out slow and silent from a bum stuck firmly to a chair. When you come nose to nose with such an

education

, it's no good staying around sniffing. I bowed, crept backwards to the door. When you shut the doors yourself, there is no need to slam.

Dry souls thrive in academies, like butterflies pinned down in a glass case. A creative mind needs air, storms, thunder, electricity.

Robert Kenny raises his beer finger. Martha brings a full tankard, glaring. Let her stare. Beer lessens the sting

of spirits. In

summa summarum

, the more beer I drink, the more sober I become. Electricity excites Stuart as the Holy Ghost excites believers. God himself seems more like a steam engine, though, one that demands heating, i.e. sermons, singing and prayers. Perhaps in future everything will run on electricity.

I will show Stuart a picture in a French book that demonstrates how electricity can produce a smile. The charge passes through cables from a wooden box with a metal cylinder on top to an old man's face. The corners of the man's mouth rise like a clown's. You laugh and there is no need even to be happy. But first I will clear my head with beer.

Â

Mary Kenny wipes her eyes.

Lucy Wilkes removes the currants from a piece of cake with a spoon.

She knows that sorrows are not reciprocal like visits to friends and family. Mary has laid the table with buns, plain cake, doughnuts and many varieties of sorrow. That Father went bankrupt; that Robert had to leave the London hospital though he had a good, well-paid job there; that he had to return to the village where his aunt makes out she knows more than a doctor; that her sister died; that Eleanor died; that her mother is ailing.

If I were sitting in a train now, making the journey north from Dover, the engine would stop, puffing.

I would see a lit station from the train window. Two women would be standing outside under a shelter. A small, bent man would be carrying passengers' bags. He would lift the suitcases on to the train. The evening sun would set behind the station. Wisps of grey, steam from the train or smoke from the factory chimneys, would blend

with the golden clouds. I would rest my forehead against the cool windowpane. I would see the small man walking empty-handed through the station door. I would notice a strange-looking chimney and a bin woven from metal. I would wonder where the women were; were they seeing someone off or did they get on the train? I would wonder why the train was not departing, why we were still waiting, why nothing was happening. Would we be stuck at this station for all eternity? The porter would go on carrying the bags, those seeing off travellers would go on seeing them off. I rest my head against the window. Goodness me, I am on a train: the village, this life. The porter carries the bags back and forth. Even the grey clouds have stopped moving.

So he just barged out, slamming the doors. Left the patients sitting there waiting, Mary says.

In front of the Kennys' fireplace, at the women's feet, Charles Wilkes is lying on the carpet on his stomach, copying a picture of a big hairy ape with long teeth and a broad grin. He has never seen a real ape, but he has seen a dancing bear. It turned round and about, and growled like the Big Black Man they met on the village road. He said: Hello, boys. We screamed and threw apples at him. It was autumn. Soon it will be Christmas, Jesus' birthday. I want a jack-in-the-box for my present, with a spring to make him jump, and a pocketknife with a sharp blade.

Â

Duchenne, Robert Kenny says to Stuart Wilkes at the door. The name sizzles with French sibilance. Frenchman Guillaume-Benjamin-Armand Duchenne was a doctor who made people smile though their faces were paralysed. Stuart takes a look.

The photograph in the book shows an old man with a bald forehead and pate, downy ears and small, close-set,

wrinkly eyes. His toothless mouth is indeed twisted into a smile. The end of an electricity-conducting lead has been pressed against both cheeks.

Duchenne was a famous man, Robert Kenny says. An illness has been named after him, though the English doctor W.J. Little wrote about the same illness before Mr Duchenne published his book. The muscles of a six-

year-old

boy with this illness will begin to waste. He will walk strangely and keep falling over. Because of the wasting muscles, the boy will end up in a wheelchair at the age of ten. He will die early because there is no cure. What do you say? Not a single illness will be called after this name of mine, not even the one that besets me.

You're just pissed, Stuart Wilkes says.

Â

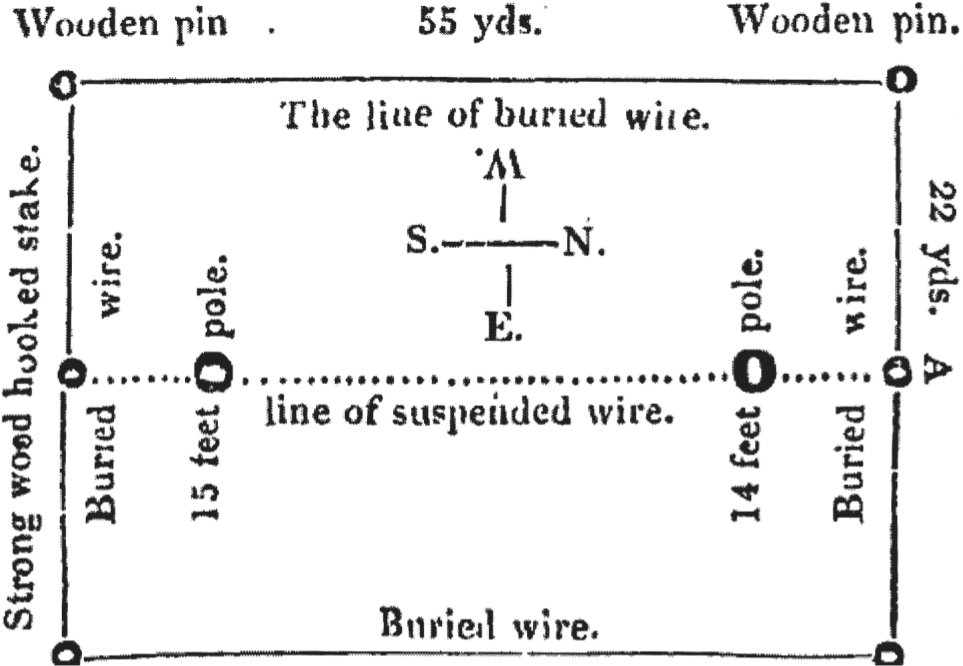

Towards evening, snow-light lingers over the landscape as Thomas Davies and Cathy and John step on to the field. Thomas wants to draw the outline for an area measuring fifty-five by twenty-two yards, as in the plan.

Thomas walks in front, counting his steps. Cathy and John follow. Each stamps their feet so that a straight, narrow path is imprinted on to the snow. North is over there, south there. Thomas pushes branches into the corners as markers. Later, when the posts are being bashed into the ground and the wires strung, they will need a compass. Electric currents in the earth run eastâwest, and the posts supporting the wire must stand northâsouth.

Posts and pegs will have to be whittled to the right length. The soil must be turned over and ditches dug for the underground wires. That is the plan. In Scotland, the barley harvest trebled thanks to electricity.

As they eat stew at home in the hot kitchen, Thomas explains that the wires conduct electricity, especially during thundery weather. Electricity stimulates the production of nitric acid, which is good for plant roots. After they have eaten and the table has been cleared, John draws on the reverse side of Cathy's paper: a square for a house and a circle bigger than the house for a cabbage head.