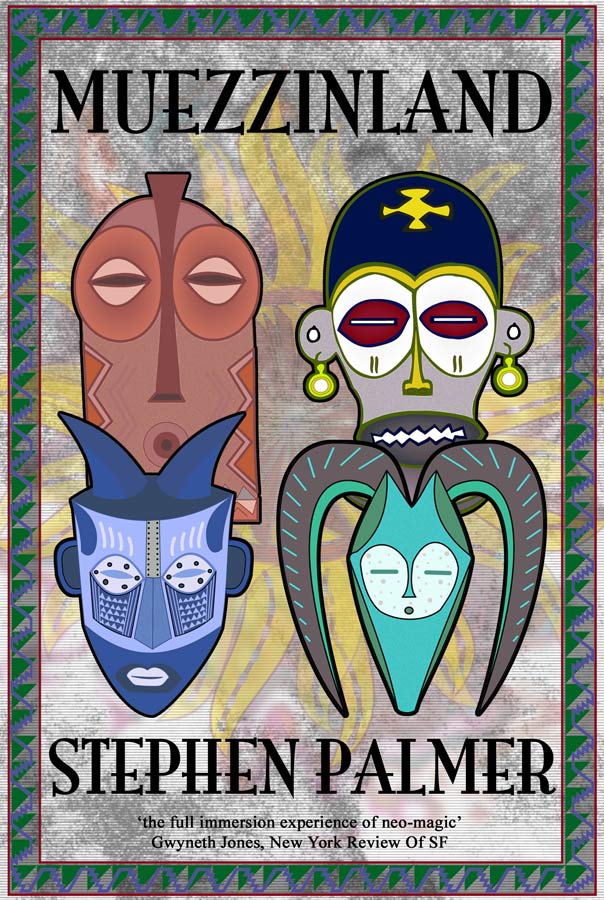

Muezzinland

Muezzinland

Stephen Palmer

Muezzinland

Stephen Palmer

Two sisters on the run, both pursued by their mother. But when this mother is the Empress of Ghana and one of the most powerful people in the world, it is no ordinary chase. And life has changed in the mid twenty second century. The aether is a telepathic cyberspace. Biochips augment human brains. AIs, concepts, even symbols can be dangerous. Mnada is heir to the Ghanaian throne, yet something has been done to her brain that has made her insane, something to send her fleeing north across jungle and desert towards the mysterious place called Muezzinland. Nshalla is relegated to the status of puppet, ignored, yet also part of her mother's plan; she follows her sister's flight, determined to discover the truth behind Muezzinland. And the Empress herself, possessing the most modern technology with which to recapture her daughters – androids, morphic tools, orbital stations, all powered by a ruthless will. But not even she can predict what might happen should the family be reunited, least of all if it is inside Muezzinland... Set in a vivid and fascinating future, Muezzinland is a novel by the author of

Memory Seed

and

Glass

.

Published by infinity plus at Smashwords

Follow @ipebooks on Twitter

© Stephen Palmer 2003, 2011

Cover © Stephen Palmer

ISBN: 9781466130524

Electronic Version by Baen Books

Smashwords Edition, Licence Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

The moral right of Stephen Palmer to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Twenty Seven Years Ago…

The Empress of Ghana awaited the creature of bioplas and metal who was her most feared servant, I-C-U Tompieme, the red and white one, the android of the aether trusted with her most important secrets. It was dusk. Outside the Accra palace she heard the chittering of monkeys and the soft tumble of fountains splashing coconut-water to the breeze. Venus shone low on the horizon. Higher up, the quartz lamps of stratostations monitoring the ozone layer flashed white.

There was a click at her door, and in he stepped. I-C-U Tompieme was two metres tall, with polished black eyes, flashing teeth, and a hairless piebald skin that spoke of one accident too many in the gene barrels of the undercity. The Empress smoothed her dress of blue silk, then sat back into the cushioned luxury of her chair.

"So my transputer shaman," she said in her deep voice, "how blow the winds of the aether today?"

This was a code question designed to ensure that nothing external had hacked into his source machines. He replied, "Like the vultures, endlessly circling."

"Good."

I-C-U Tompieme flashed his sabre-smile. "And so to the business of the day, your majesty."

The Empress could not hide the glee she felt at the report she was about to hear, for something deep within her scheming mind told her that success was hers today. "Tell me all," she whispered.

"It is as we thought. The aether has reached a level of complexity sufficient for it to begin reorganising itself. The reports of virtual people are true. Transputers across the globe are being forced to remake themselves into the equivalents of personality, so that they may cast themselves in coherent form across the electromagnetic ocean. Soon these virtual people will cause us difficulties, and eventually endanger us, for they will organise themselves along cultural lines. Some at least will be aggressive."

"These virtual people cannot be controlled," said the Empress. It was not a question. But the fact was the focus of her plans for the future.

"Indeed not. But one does not control a termite nest by trying to direct each individual insect. One reaches for something larger."

"And that is what we will do," said the Empress, excitement making her stand to face her servant. "Soon the virtual people will create their own gods, and it those deities who we will control. Such gods will be the symbols of vast architectures of software. To direct them will be to direct the civilised world."

"Your majesty has the virtue of vision."

The Empress nodded, her eyes glistening with joy. "Yes, my transputer shaman. But at the moment I am just one of five equals. I must become the first amongst equals, and then—who knows, maybe in just a few decades—the undisputed first."

"So it shall be," said I-C-U Tompieme, respectfully inclining his head to the ground.

There came a voice from the corridor outside her door. "Is that him?" the Empress asked, suddenly reduced to the stature of a middle-aged woman.

I-C-U Tompieme glanced at the door. "It is him. I shall report tomorrow on the progress of my analysis. Enjoy yourself tonight, your majesty." He grinned, and the Empress shivered at the humanity shown by this inhuman.

He slipped through a secret door, seconds before a maidservant knocked, entered, then announced the presence of the Empress' husband.

"Have him meet me at my boudoir," she replied.

Walking the short distance to her evening suite, the Empress checked her appearance in the many mirrors that graced the walls, until at a low door of plain wood she paused, listening. From inside came the sound of boots upon marble. After a moment's hesitation she hastened in, her dress hissing as she did.

"My darling," she said.

There he stood—her husband of two weeks, Ruari Ó Bráonain, a lord of the west who had made it to Lagos in Nouveau-Nigeria, where he had settled to become a musicologist. Her husband. The man who would help her make a child.

"Darling," he replied, his accent not so thick that she could not understand what he said. "My true love." Oh, he was in love all right, despite the match being one of opposites. But that was how it had been planned. "Darling, I missed you yesterday."

"And I missed you."

"Tonight!" he said, pulling a sachet of champagne from his jacket pocket, and grinning lasciviously. "Look what I found. Moët!"

"Only the best for us," the Empress remarked.

"Well, we have to get in the mood," he said. "Tonight we make our first child."

The Empress laughed, not out of amusement or excitement, but to release the tension she felt at this most crucial time in her plans. "My red headed lover," she whispered.

"Our first child."

"Our daughter," she corrected him.

He seemed not to be listening. "And what shall we call your heir?"

The Empress was not expecting this question, but after the briefest pause she replied, "We will name her Nshalla."

Chapter 1

Nshalla stood yawning on a hilltop a kilometre north of Accra, as the sun rose pale above perfectly still banks of mist. Below her, the steeples and aether aerials of the city poked up through haze blankets, the steeples bearded with dew soaked moss, the aerials clanking as chittering monkeys swarmed up and down them. Far off, an elephant trumpeted.

Nshalla checked her backpack. Her dress, clashing green and yellow silk, was thin, allowing the pack straps to bite into her shoulders. She fidgeted. Again she scanned the dusty track leading up from the city. No sign of Gmoulaye. Surely her best friend would not desert her now?

The first rays of the sun struck her. It had changed from white to yellow. Into a cloudless sky it rose, as Nshalla fretted and checked the time on her belt transputer.

A song. She could hear a tribal melody sung in a woman's voice.

Gmoulaye approached. She was taller even than Nshalla, and built like a warrior. Naked except for an array of cloth belts slung like sashes over her shoulders, she approached, teeth glinting as the sun caught them. Her skin, dark even for a Ghanaian, was beaded with sweat, dusty below the hip, and her breasts were like empty triangular water bags.

With a cry she greeted Nshalla. "I am here. Wait for me."

"I wasn't going to run off," Nshalla replied.

They hugged one another. Nshalla appraised her friend. Attached to the belts were curious items, Nshalla presumed related to the journey they had agreed to undertake. Apart from the usual transputers, their matte screens black as a beetle's back, Nshalla noticed amongst other sundries a small djembe drum and an mbira with steel tines, various food gathering tools, and a roll of cloth. This latter would be her bed. Gmoulaye was a woman of the land.

"Shall we go now?" Gmoulaye asked. "Your mother will be after you."

Smiling, Nshalla shook her head. "She's still in Lagos with the Queen of Nouveau-Nigeria. It'll take some days for her entourage to come back—because it's a state visit they're walking all the way. We've time enough to make Ashanti, and then we'll be out of her grasp."

Gmoulaye glanced down at the shrouded city. "Out of her personal grasp, yes. But her agents?"

"We'll recognise them."

Gmoulaye laughed, and her earrings glinted as they shook.

What are those jewels?" Nshalla asked.

Gmoulaye pointed north-west. "Walk! Ashanti City is two hundred and fifty kilometres away." They began to walk, adopting a casual pace. Gmoulaye continued, "These are my sister's earrings. She gave them to me."

"She knows where you're going?"

Gmoulaye hesitated. "I have not broken our secret, but I had to explain that I was making a trek. It was only a half lie."

"And the earrings?"

"One is my bank, the other is a database. Nine hundred terabytes."

Nshalla whistled. The earrings were spheres, pearly white, each held in a silver vulture's claw: optical memory on a vast scale.

They walked on, but as the morning progressed heat began to make them wilt; Nshalla's plaited headband became sweat soaked. Clouds of flies gathered around Gmoulaye; her djembe skin had recently been cured in cow dung. She sprayed the instrument with a herbal insect repellant. "I had to bring the djembe," she explained, "else be struck dumb."

An hour before noon they took shelter under a baobab tree. Nshalla gazed out at the parched woodlands. Copses greened the brown land, the boles of the trees wizened and black, and between them swayed giraffes, chewing leaves. Far off amid cacti clumps there was a waterhole; Nshalla heard the faint echoes of thirsty plains animals, and she saw a column of dust, and in that a pair of spiralling vultures. She scanned the land north-west. Ten days away lay ancient Ashanti City, and there a certain library resided.

"Why do you believe Princess Mnada made for Ashanti?" Gmoulaye asked, in between spitting out fragments of the root she was chewing.

"It's the obvious place to go," Nshalla replied. "Tsevie in Togo would be too dangerous because Togo is friendly with Ghana. Dzigbe in the Red Republic is dangerous because of bandits disguised through the aether as goatherds. No, she'd make for Ashanti. Besides, she wanted to find Muezzinland. She didn't think it a fable, she really believed in it."

"And the fables say Muezzinland is in the far north."

"The north. Let's not depress ourselves."

Gmoulaye looked askance at her friend on hearing this remark. Some time later she said, "I wonder why Mnada just left? It was so sudden."

Nshalla did not answer. Silence descended.

Gmoulaye tried a third question. "What exactly did you tell the Empress?"

Nshalla pressed a button on her holographic ring, causing a sheet of green text to appear in the air. It read:

VOCAL RECORDING SERIAL NUMBER: 638-g3928-Acc09-Gha-Afr

TO THE EMPRESS OF GHANA. Dear Mother, I'm truly sorry that I can't tell you this in person, but once you've heard this letter you'll understand. I can't just let Mnada vanish into nothingness. I've got to find her. I wish you could have done something. Perhaps you have, and already your servants are scouring Ghana, or perhaps you have other plans. In any case, they do not involve me. But Mnada is my sister and so I've got to follow her. All I know is that she went north, looking for Muezzinland. I'll follow her and find her. I feel it's the least I can do even though a few weeks have passed since she disappeared. Please don't try to stop me. Your people need your full attention. I'm sure you'll let me go unopposed. I promise to bring Mnada back to Accra, and then we can all celebrate! We can all be a family once again. Always your respectful and loving daughter, NSHALLA.

When the afternoon shadows lengthened, they departed the baobab tree. With the heat of midday gone they were able to walk with a firm tread, pausing only to refill their waterskins in a stream that had not yet dried up. Nshalla's analytical transputer indicated that the water was not polluted enough to harm them.

As evening came Nshalla found that the rhythms of the day had brought a feeling of calm to her, as if, merely by walking twenty five kilometres, she had rejuvenated her body. Although she was the Empress' unimportant daughter, her life had still been focussed upon Accra, and too rarely did she step outside. She felt that this great venture could somehow create a new Nshalla, as if the Aphrican air, its water, even its dusty red soil, could infuse themselves into her body and replace pungent city grime and smelly sweat.

But there was another aspect. She looked at Gmoulaye, walking hip-sway style a few metres ahead. Gmoulaye was a woman of the earth, no puffed-up city dweller. Though Gmoulaye, like everyone, had a biograin augmented brain, her central character was fixed by tribal culture. The scarred and dusty image Nshalla saw was reality: the aether did not warp it. Nshalla realised that this was why she had been so sure of choosing Gmoulaye for a companion, for in Accra it was impossible to be certain of anybody's image, and therefore character. The electromagnetic ocean that was the aether made sure of that.

As the sun set they decided to make camp in fern trees. While Gmoulaye gathered firewood Nshalla lay on her back, gazing at the stars as they emerged.

A friendly foot shoved at her shoulder. "You think fires light themselves?" Gmoulaye asked.

Nshalla smiled. "I was just watching."

Gmoulaye glanced upward. "No one shows a child the sky," she said.

Nshalla knew that Akan proverb. "But I'm not a child," she complained.

"You are young. Onyame is up there, he is everywhere."

Nshalla jumped to her feet and began to stack the wood. "I don't believe in him. I don't worship tree trunks. If I did, the aether would make my skin as dark as yours." She paused. "No, I'll remain me. Whoever I am."

Gmoulaye made a face. "It can't be

that

bad being you."

Nshalla shrugged, and with a gas lighter started the fire. Gmoulaye bent to pick up stones, which she threw at a number of bats in nearby baobab trees, stopping only when every last bat had been driven off.

"Why did you do that?" Nshalla asked.

Gmoulaye grunted and began to place mud jacketed sweet potatoes around the crackling fire. "They were Sasabonsam. We are travellers, aren't we, away from the safety of the city lamps? Sasabonsam is evil, preying on the likes of us, ready to unroll its legs and grab us by the armpits, then take us away to its lair."

"Really?" Nshalla shivered. She tried to remember when she had last been out of Accra at night. Ten years ago? Fifteen? And then she had been a child with attentive servants.

"You are lucky I am here. Nothing gets past my wisdom. Sasabonsam is in league with abayifo witchcrafters."

Already night had fallen, as if a cosmic eyelid had been shut. Insects stridulated. Twigs in the fire popped and cracked as the sap boiled. Waiting for her potatoes to cook Gmoulaye made music, alternately singing a plaintive lament for peace and playing her mbira. Nshalla watched the wrinkled fingers dance from tine to tine, listening to the hypnotic buzzing resonance of the instrument… and then an especially loud crack made her start.

"Sleepy head," Gmoulaye muttered. In a can she had boiled a little millet porridge, which she served in a calabash with the sweet potatoes. Nshalla, head still muzzy, snorting out acrid smoke from her nostrils, wondered if she was imagining the honey set to one side. She picked up her spoon.

"Honey?" she said.

"A hive half a kilometre off," came the nonchalant response.

They ate their meal, then settled down. Gmoulaye produced a dagger and an Okinawan stun-gun from her capacious belts. Her stomach squeaked and growled as she digested the meal she had eaten; Nshalla's was likewise noisy, but later it settled.

Gmoulaye said, "Can you hear any animals?"

Quickly Nshalla sat up. "No. Can you?"

"No."

"Good."

"What did you bring, metal-wise?"

Nshalla glanced at her backpack. It lay under her dress, which she had flung away; now she sat wrapped in her bedroll. "A dagger, like you, but mine's stubbier. And a dart pistol. And plenty of refills."

Gmoulaye nodded. "Wise of you. Things might get frightening further north, depending on how far we're going…"

Nshalla heard the query in the remark. "Muezzinland can't be impossibly far, else Mnada would never have heard of it. It's no further than Ouagadougou."

"How can you be sure?"

"Ouagadougou is the worst of all possible worst cases, there's no doubt."

"So you say," Gmoulaye said, "but we can't be certain of anything in this fragmented world."

Nshalla thought she understood what Gmoulaye was feeling. "You just don't want to leave Ghana. I understand that. But we'll have to. I expect it won't be far."

"What a peculiar mix of optimism and pessimism you are," Gmoulaye remarked, eyeing Nshalla as she did.

"We've known each other almost a decade. Don't tell me you're having second thoughts."

Gmoulaye shook her head. "My mind wanders."

Nshalla shrugged. She held up a transputer. Its screen glowed orange as it responded to the warmth of her hand, and lines of pictsym scrolled across its layered screens. "This can be a guide," she told Gmoulaye. "I can access maps, so we won't get lost."

"Inaccurate maps."

"Possibly."

Gmoulaye grunted. "We have little ground knowledge. This is a trek into the unknown. Once we are north of Ashanti we will be like two termites lost and far away from their nest. Any wandering anteater or chimp will just lick us up."

"Now you're being pessimistic."

Gmoulaye seemed to jerk out of her mood. "Yes. Time to sleep. I'll play you a sleeping rhythm. Goodnight."

"G'night, Gmoulaye. And thanks for coming."

"It is a change for me. Now sleep well."

Nshalla lay back, piling up a hillock of earth under the small of her back, wriggling until the side of the bedroll warmed by the fire covered her chest and legs. A pattering rhythm began. Gmoulaye's fingers tapped against the djembe skin, two notes repeating in polyrhythmic unison, until, at the junction of waking and sleep, Nshalla could see hypnagogic images against her eyelids, coloured motes, each a drum note. They spread into a matrix… or was it aether static received by the biograin hierarchies embedded in her brain? As the question came to her, sleep arrived too.