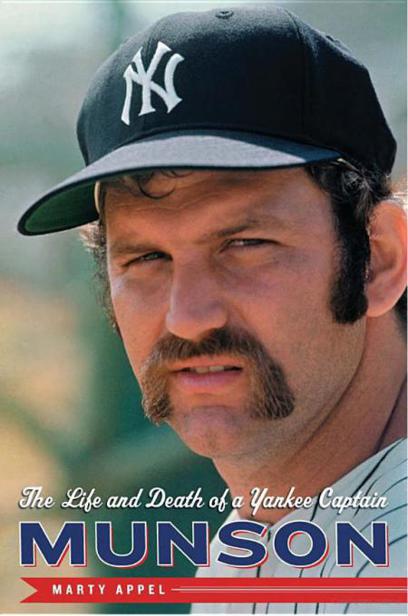

Munson: The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain

Read Munson: The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain Online

Authors: Marty Appel

Now Pitching for the Yankees

Baseball: 100 Classic Moments in the History of the Game

(with Joseph Wallace and Neil Hamilton)

Slide, Kelly, Slide

When You’re from Brooklyn, Everything Else Is Tokyo

(with Larry King)

Great Moments in Baseball

(with Tom Seaver)

Yogi Berra

Working the Plate

(with Eric Gregg)

Joe DiMaggio

My Nine Innings

(with Lee MacPhail)

Yesterday’s Heroes The First Book of Baseball

Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner

(with Bowie Kuhn)

Tom Seaver’s All-Time Baseball Greats

(with Tom Seaver)

Batting Secrets of the Major Leaguers Thurman Munson: An Autobiography

(with Thurman Munson)

Baseball’s Best: The Hall of Fame Gallery

(with Burt Goldblatt)

To Brian, Katie

,

Deborah, and Lourdes

,

and in memory

of

Irving Appel and Bobby Murcer

At such a late hour, it took only twenty-five minutes for Bobby and Kay Murcer to drive Thurman Munson to Palwaukee Airport in Wheeling, Illinois, north of Chicago.

The Yankees had concluded their two-game series with the White Sox, and Munson, his knees hurting and unable to catch, had left that final game early, signaling to Billy Martin with a nod of the head that he needed to be replaced as first baseman. First base was supposed to ease the strain on his arthritic knees, but ever since he’d awkwardly fallen backward a few weeks earlier on a close pitch, he just wasn’t the same.

The same, for him, meant a high level of proficiency, bordering on Hall of Fame greatness. But now, three straight seasons of championship play were coming to a close for the Yankees, and a great decade of performance was also winding down slowly for the thirty-two-year-old captain of the team.

Ah, but that was an hour ago. The Yanks had scored an easy victory, making the clubhouse loud and cheery on this getaway night,

August 1, 1979. The Murcers had agreed to drive Thurman to the airport, where they could see his new Cessna Citation jet up close. It was late at night—it was actually August 2 already—but baseball’s schedule forces its participants to live late hours, and this didn’t seem odd at all.

Except, of course, for Thurman leaving on his own plane and not flying on the big Delta charter out of O’Hare Airport with the rest of the Yankee team. Now

that was

pretty unusual.

Players just didn’t do things like this. The great Bob Feller became a pilot after his playing career to get from one minor league park to another as he built a postplaying career out of personal appearances. His old Cleveland teammate Early Wynn had a pilot’s license. So did Bob Turley, the former Yankee Cy Young Award winner, who used a private plane for business travel. For the most part, the older players simply couldn’t afford such a hobby.

Ken Hubbs, a Chicago Cubs infielder, had died piloting his own plane fifteen months after winning the National League’s 1962 Rookie of the Year Award.

“Thurman saw himself as more of an Arnold Palmer,” says his older brother Duane, who for a time worked as a sky marshal. “He liked Palmer—his success at his field, his success in the business world, and the fact that he learned to pilot his own plane. I think Palmer was really his role model.”

The Murcers, who had known Munson for a decade, had invited Thurman and Lou Piniella to stay with them in their Chicago apartment during the brief series. Bobby had been playing for the Cubs until just about a month before, and he still had his rented apartment there. It had been a great visit, all of them celebrating Bobby’s return to the Yankees; one bright spot in an otherwise dismal 1979 season.

Murcer could be direct with Thurman, and he was on this night.

“Fly with you in that crazy thing? Not me, Tugboat,” he said, calling Munson by one of his clubhouse nicknames.

Well, Thurman had at least extended the invitation. At the very least, the Murcers agreed to drive to the end of the runway and watch him take off. It was fun, in a way, late at night, the coolness of the summer evening, the temperature about sixty-seven degrees, Bobby and Kay feeling like teenagers somewhere in Middle America at an old-time airstrip, not just a half hour from a major city.

The Murcers agreed that the jet was beautiful. Thurman hadn’t painted it in pinstripes, but he had put an identifying N15NY on the tail, and for those who thought he was hoping to get traded to Cleveland, there was a message in that. He was stamping his prized possession as “Yankee.”

He ran his hand over the exterior, the shiny paint job not that old. He had gotten the $1.25 million twin-engine jet twenty-six days earlier, despite warnings by some that it was too much plane for him. But Munson, like most elite athletes, was not the conservative type when it came to risk-taking.

He said good night to the Murcers, who then drove to the end of the runway, and Munson climbed aboard his sleek prized possession, his aching knees settling into position. It was beautiful inside too. Sitting in the pilot’s seat, the yoke in front of him, the airspeed indicator at eleven o’clock, the vertical speed indicator at three o’clock, the landing gear lever right there at his powerful right hand … it was all so magnificent! What a machine!

And so he went through his maneuvers and took off without delay, there being no other incoming or outgoing traffic at such a late hour. He slightly dipped his wings as he flew over the Murcers.

“The man’s crazy,” Bobby said, as they got in their car and headed home. “But that’s Thurman.”

The four-hundred-mile flight to Canton, Ohio, would be accomplished in just about an hour, with some bad weather keeping him on his toes. But this was the whole point of it all, wasn’t it? If the jet could reduce the fly time over his Beechcraft King Air Model E-90, a prop plane, well, that was the goal. Get your own plane, take off

when you’re ready, and spend extra hours and extra days with the family—including four-year-old Michael Munson. (“That little guy, he’s a handful,” he acknowledged to friends.) Diana loved when he’d be home, because Michael would sleep through the night.

And of course she loved when he was home because theirs was one of the great love stories in baseball.

Up in the sky, passing over Lake Michigan, the lights of Fort Wayne, Indiana, in view, Thurman relaxed. He felt at home up there, although he’d only been flying for eighteen months. It was he and his plane and his wits.

During spring training, he had spoken to Tony Kubek, the old Yankee shortstop who now broadcast for NBC.

“I think it’s great,” he told Tony, “the feeling of being alone for an hour or two by yourself. You’re up there, and nobody asks any questions. You don’t have to put on any kind of an act. You just go up there and enjoy yourself. You have to be on your toes, but it’s just a kind of relaxation when you spend a lot of time by yourself, and I need that. I also need to get home a lot, so I love to fly.”

This was all so perfect. He was right where he wanted to be.

Some years earlier, a strapping truck driver who saw himself as more athlete than teamster would sit alone in the cab of his rig, perhaps thinking the same thoughts. Darrell Munson, Thurman’s father, would think of the beauty of his independence, no one asking him questions, just on his toes, relaxing, putting America’s highways behind him.

Maybe the two of them, long estranged, the father and his youngest son, had more in common than they realized.

Baseball wasn’t cool in the 1960s.

During the “Summer of Love” not many young people were talking about Carl Yastrzemski. No one at Woodstock wondered whether the Mets could really go all the way. Few among my friends were particularly impressed when I took a summer job answering Mickey Mantle’s fan mail for the Yankees in 1968. And it was the same when I was offered, and accepted, a full-time position in the public relations department midway through my senior year in 1970.

I was one of two people in my college who subscribed to

The Sporting News

(my roommate was the other)—but I couldn’t watch baseball on Sundays in the fall when the one TV in the dorm was tuned to the NFL—even during the World Series!

As Mantle, Banks, Clemente, Mays, Aaron, Mathews, Maris, Kille-brew, Koufax, Drysdale, and Colavito moved toward the twilight of their careers, few stars appeared to replace them. The mid-to late sixties gave us Reggie Jackson, Johnny Bench, and Tom Seaver, but not many other attention-getters.

But then, in the midst of this decidedly uncool period of baseball, the once proud Yankees, now mediocre and dull, found a player named Thurman Lee Munson to proudly take them to their tomorrows.

Thurman was a throwback; a lunch-bucket kind of guy who was all jock and no rock. He wasn’t going to win over New York by being Joe Namath or Clyde Frazier. He liked Wayne Newton music and, in what was arguably the worst-dressed decade of the twentieth century, the 1970s, he was the worst of the worst. His wardrobe featured clashing plaids and checks made of the finest polyester. Socks were optional.

It was an everyman look that went with his regular-guy demeanor. He liked to pump his own gas, even in New Jersey, where you weren’t allowed to, and even when he became famous. On occasion, thinking he was the attendant, someone would pull up next to him and say, “Fill ’er up”—and he would! He’d pump the guy’s gas, collect payment, and hand it to the station manager. I was with him one day when he even washed a guy’s windshield while filling up his gas tank. I suspect the guy drove away thinking,

That gas station guy looked a lot like Thurman Munson

.

No, cool wasn’t his game. He was going to win them over the old-fashioned way—with gritty determination and a focus on respecting the game and playing it with heart. He would honor the tradition of the Yankees and wear the uniform dirty and proud, and would not tolerate mediocrity from his teammates. He would restore the Yankees to their prominence in the sports universe, the place they occupied when all seemed right in the world.

We would fall in love with his game and realize, watching him, that cool didn’t have to count in baseball. Thurman Munson made it a virtue to be

uncool

, winning over the young and the hip with his decidedly unhip approach to his profession.

He wasn’t Mickey Mantle—he wasn’t born with those looks or that

body, or that particular style that made “the Mick” a pinup boy for baby boomers. But he was Mantle’s heir. Mickey retired in spring training of 1969. Munson made his debut later that season, giving the Yankees continuity in their ongoing parade of stars.

By 1970, my first year as assistant public relations director, New York had begun to latch on to his Ohio grit and guts. And since my career began along with his, he would become “my guy,” the player I would grow up with in the Yankee organization, the one I’d write about and collaborate with.

I loved watching Thurman Munson play baseball. He just knew how to play the game, knew how to win the game, knew how to lead. He was grumpy but he had a great sense of humor and a magnificent sense of self. He was the kind of guy you wanted to be friends with.