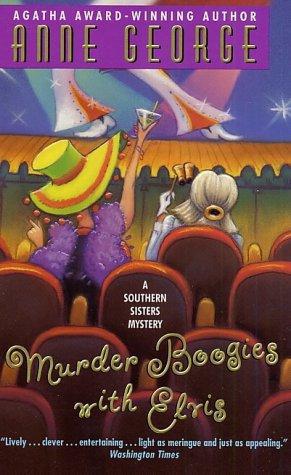

Murder Boogies With Elvis

Read Murder Boogies With Elvis Online

Authors: Anne George

Tags: #Contemporary, #Suspense, #Amateur Sleuth, #en

A Southern Sisters Mystery

To Ruth Cohen, my agent, and Carrie Feron, my editor,

who have been with me, Patricia Anne,

and Mary Alice from the beginning.

My love and deepest appreciation. You’re the best.

I was lying on my stomach under the kitchen sink,…

Looks funny up on the mountain without Vulcan,” Fred said,…

The Alabama Theater is one of the great old movie…

Oh, happy day! We’ve made our plane reservations. The three…

The man looked to be in his late thirties. He…

“Impregnate Marilyn?”

The sound of Fred taking a shower woke me up…

While I was out walking Woofer, Marilyn called and left…

Marilyn was asleep when we got home, or at least…

Fortunately I was sitting in one of the wicker chairs…

Fred woke me up when he came in around five-thirty.

It took Debbie more than an hour to get me…

Larry Ludmiller didn’t come home last night,” Yul Brynner announced…

Oh, Lord.” Dusk moaned, leaning over Larry. “Somebody call nine-one-one”.

When I got in my kitchen, I sat down at…

Supper was a quiet affair. Before Fred came in, I…

Guess what! Joanna’s moving. I’ve been feeling some flutters for…

Two things happened the next morning. Larry Ludmiller regained consciousness…

The side door of the Alabama Theater was unlocked. The…

May fourteenth was a perfect day, weather-wise. A late cold…

I

was lying on my stomach under the kitchen sink, eating a peanut butter and banana sandwich and listening to Vivaldi’s “Spring” when icy cold hands grasped my ankles. I screamed, reared up, and banged my head on the drainpipe so hard that zigzag lights streaked across my vision. The next thing I was aware of was being dragged from under the sink and hearing a very familiar voice saying, “What on God’s earth is wrong with you?”

My chin hit the kitchen floor with a clunk and the zigzag lights streaked again; pain from both blows met in the top of my head.

“Are you okay?”

Maybe, I thought, if I just lay there she would go away—“she” being my sister, the boss of the world. The pain would lessen, Vivaldi would move on to “Summer” and then to “Winter.” Eventually I would get up, get some ice for the knot that was swelling like

a balloon on the back of my head. If I were lucky, the brain damage would be minimal.

“You weren’t trying to commit suicide, were you, like that poet woman? Tell me you weren’t trying to commit suicide, Mouse. That would be a terrible thing to do to me.”

“What?” I struggled to a sitting position and looked up at Mary Alice. Way up. She’s six feet tall (she says five-twelve) and admits to two hundred fifty pounds.

“Well, I know I haven’t been around as much lately since I’ve been seeing so much of Virgil, but I didn’t think you were that depressed.”

“What the hell are you talking about?” I touched the back of my head tentatively. “I may have a concussion, but I’m not suicidal.”

“Well, what were you doing under the sink?”

“Putting down some of those tile squares. A couple of them weren’t sticking good, so I was putting weight on them. Lying on them for a few minutes.” I looked down and saw my peanut butter and banana sandwich squished on my T-shirt. “Actually I was eating my lunch. And the poet you’re thinking of is Sylvia Plath. And it was a gas stove she stuck her head in, not a sink.” I held up a hand. “Help me up.”

Sister grabbed me with the cold hands that had started the trouble and pulled me up.

“How come your hands are so cold?” I asked, walking slowly to the kitchen table and easing into a chair. I quickly learned that if I didn’t move my head suddenly, the pain was a simple throb. “You scared me half to death.”

“I was getting ice for a Coke when I looked over and saw half of you sticking out from under the sink.”

“Well, would you get me a couple of pieces now? Just wrap them in a paper towel.”

She opened the refrigerator. “You want some Coke and some aspirin, too?”

I forgot and nodded my head. Pain rattled around in there.

“I may really be hurt,” I said. I closed one eye and then the other. Was the left eye a little blurry?

“Of course you’re not. It’s just a bump.”

Sister handed me the Coke, aspirin, and a paper towel with ice in it. I swallowed the aspirin and tried the eye test again. I looked through the bay window at Woofer’s igloo doghouse. Right eye first. Okay. Left eye. A couple of floaters.

“I have floaters in my left eye,” I said. “I think I’ve jarred my retina.”

Sister sat down across from me. “Doesn’t mean a thing. You’re fine. I have floaters all the time. One looks like one of those little white mealy worms Grandpapa used to fish with. Caught all the crappie with. Comes and goes.”

“You have a mealy worm floater?”

“Sometimes. Comes and goes.”

I held the paper towel with the ice in it against the back of my head and looked at Mary Alice for the first time since she had come in. Really looked at her. The view from the floor didn’t count.

“You look very spiffy today,” I said. She did. She was wearing a pink pantsuit and her hair was a darker blond than usual. Her bangs were pulled to one side and her skin glowed.

“Thanks. I’ve been to Delta Hairlines, and there was a lady there giving free makeovers advertising some

new cosmetics for seniors. I told her I was only sixty-four, but she gave me one anyway.”

“Sixty-four, huh?”

Sister didn’t answer that. The truth is that she’s sixty-six, but on her last birthday she decided to start counting backward. I’m five years younger than she is, or at least I was. In a couple of years I’ll be older than she is and soon she won’t qualify for senior-citizen makeovers.

“I bought some of it and would have gotten you some but our skin tones are completely different.”

She was telling the truth about this. Everything about us is different. She has olive skin and brown eyes, and I have fair skin and hazel eyes. I used to have strawberry-blond hair, and Sister was a brunette. Now I’m gray and she’s usually strawberry-blond. Add to that the fact that I’m a size six petite—and Lord knows what Sister is—and is there any wonder that when we were children and she told me I was adopted, I believed her? So did everybody else. I’m just grateful that we were born at home so there was no chance that we had been mixed up at the hospital.

I closed my right eye again. One of the floaters in the left did look a little like a mealworm. I looked from one side to the other.

“Are you doing that or are you having some kind of spell?” Mary Alice wanted to know.

“I’m doing it.”

“Good, because I came by to tell you the news. Virgil and I have set the date.”

“For what?”

“For our wedding, Patricia Anne. Don’t be dense.”

“Dense? I didn’t even know you were engaged. What happened to Cedric?”

“Who?”

“The man you were engaged to last I heard.”

“Oh, I think that’s over with.” She took a sip of Coke and looked thoughtful. “I mean, he’s in England and all. I’ll let him know, though.”

“That would be thoughtful. You could invite him to the wedding.”

“Well, our engagement never was very serious.”

Sarcasm is totally lost on this woman.

“Anyway,” she continued, “the wedding is going to be the fourteenth of May. Virgil’s retiring the first of April, and we’re going to buy an RV and go all over the West for our honeymoon. Doesn’t that sound like fun?”

Virgil Stuckey, who might or might not soon be my brother-in-law, is the sheriff of St. Clair County. He is a very nice man, sixty-five years old, and larger than Mary Alice. The RV had better be a big one.

“It was Virgil’s idea. Will Alec took me to New York for my first honeymoon and then Philip took me to Paris and Roger to St. Croix. Virgil said this would be something different.”

“He’s right.” And a whole lot cheaper. Sister was breaking her pattern in marrying Virgil. The other three husbands had all been very rich and each had been twenty-eight years older than she was. But when you’re sixty-four (-six), it’s hard to keep that pattern going.

I wondered how closely Sister had looked at RVs. I shifted the wet paper towel on the back of my head and considered how my husband, Fred, and I would get along on a long trip in an RV. We’ve been married almost forty-one years and seldom have a cross word, but I had an idea that we would be at each other’s

throats by the time we reached the Mississippi River. The truth is that we don’t travel well together.

“Do those things have bathrooms?” I asked, remembering a trip across South Carolina when Fred kept saying, “Next exit,” and I thought I would pop.

“I’m sure they do.” Sister frowned slightly. “Wouldn’t you think?”

I shrugged. Pain shot up my head. Damn. “Find out.”

“I will. Virgil doesn’t need one often, though. He has a very good prostate. He says the doctor told him he has the prostate of a twenty-year-old.”

“Good for Virgil.”

“And for me.” Sister grinned.

I ignored this and aimed Sister in another direction. “Have you made any plans for the wedding?”

It worked. She clasped her hands and leaned forward.

“It’s going to be a small one, just family. And we want to have it at some little country church like John John Kennedy and Carolyn Bessette. Bless their hearts.” She sighed and tapped a packet of Sweet’n Low against the table. “I was all set to vote for him someday.”

I thought of the beauty and possibility that had been taken away so suddenly. Of the little boy saluting, the man kissing his bride’s hand. Pain again slammed the top of my head.

“Anyway, that was such a nice wedding,” Sister continued, “and I’ve had every other kind.”

“True.” I couldn’t match the husbands and ceremonies, but there had been a big church wedding, a home wedding, and an elopement.

“I can see a cream silk dress for me—long, of

course. And what about magenta for you? You’re going to be the matron of honor. And I saw a wonderful color called sunflower for the girls. We’ll look like a spring garden.”

“The girls?”

“Debbie, Marilyn, and Haley. Virgil’s daughter is going to be in it, too.”

Magenta and sunflower? Dear Lord. I did a quick calculation. My daughter, Haley, would be more than five months pregnant on the fourteenth of May. I could imagine how excited she was going to be about wearing a sunflower-colored bridesmaid dress. About as excited as Sister’s daughters, Marilyn and Debbie, would be.

“You haven’t told them yet, have you?”

“I’m going to surprise them.”

I put the wet paper towel on the table. “Mary Alice, I don’t want to wear a magenta dress.”

“Of course you do.”

“I do not. I’ve never worn magenta in my life.”

“Well, you should have. We’ll put a rinse on your hair so you won’t look so washed out. I swear, Patricia Anne, you need to take some iron or eat more. When I saw those skinny white pitiful legs sticking out from under the sink, it’s no wonder I thought you were dead.”

“Go home,” I said.

“Okay.” She stood up. “But I didn’t tell you that Virgil, Jr., got Virgil and I tickets for the Vulcan benefit at the Alabama Theater tomorrow night.”

“Me,”

I said. “He got Virgil and

me

tickets.”

“You mean Fred and you? He sure did. Wasn’t that nice? Four seats on the front row. We’re all going out to dinner afterward. It’ll give you a chance to meet him.”

“Go home,” I said.

Sister put on her jacket. “Virgil, Jr., is an Elvis impersonator. Supposed to be real good. Of course, the white jumpsuit and sideburns take some getting used to.”

I threw the wet paper towel at her. She ducked.

“Your tiles are coming loose under the sink. I’ll call you when you’re not so cranky.”

The only thing on the table to throw was the sugar bowl, and I didn’t want to break it. She was going out the door anyway.

Magenta and sunflower. Yuck. I got up, careful not to move my head too quickly, and looked at the tile. Damn. A couple of them were coming unstuck. No way was I going to lie back down on them, though; I’d epoxy them later. I closed the cabinet door, scraped the peanut butter and banana off my chest with a kitchen knife, and pulled the T-shirt gently over the knot on my head. Then I threw the shirt in the washing machine and went to take a shower.

The hot water felt wonderful. By the time I got out and put on some clean corduroy pants and a turtleneck, I was almost cheerful. I went into the room that used to be our sons’ room—and which has metamorphosed into a sewing, ironing, computer room—and checked my e-mail. No new messages. Haley had had her amnio test several days earlier, and I was hoping for news. But in a few weeks, this e-mail business would be over. She and Philip were coming home. Home from Warsaw, Poland, where they had been since last August. Fred, Mary Alice, and I had gone to visit them for Christmas, and the e-mail lines had stayed busy, but it was going to be so good to have her home, to see her getting larger and larger with the baby she had wanted

for so long. Haley’s first husband, Tom Buchanan, had been killed by a drunk driver just as they were considering starting a family. It was a blow that she would never fully recover from, but she had met Dr. Philip Nachman at her cousin Debbie’s wedding and had finally fallen in love again. Philip was almost twenty years older than Haley and had two grown children. He wasn’t anxious to start another family, and their relationship was off and on for several months. Haley won. They’re married, she’s pregnant, and Philip is thrilled about it. He’s an ear, nose, and throat specialist, and the day after their wedding they left for Warsaw, where he was teaching a seminar at the medical school.

I chewed on a fingernail. The amnio results should be in by now. And Haley had promised to let me know as soon as she heard something. Surely everything was all right. Surely. I took a deep breath, went into the kitchen, and fixed myself another peanut butter and banana sandwich.

April isn’t the cruelest month in Alabama; March is. When Sister had come in, the sun had been shining. Now a bank of dark clouds had rolled in from the west, and it looked like it might rain soon. Woofer ambled from his house, shook himself comfortably, and went over to the elm tree and hiked his leg. The elm tree has a white stripe around it after years of this activity.

I opened the door and called him inside. He looked from me to his igloo, trying to make up his mind. That igloo is mighty comfortable on a windy March day.