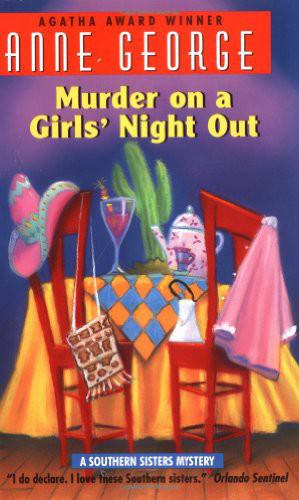

Murder on a Girls' Night Out

Murder on a Girls’ Night Out

A Southern Sisters Mystery

For Mary Elizabeth, who makes life fun

Mary Alice flung her purse on my kitchen table, where…

After I retired from teaching, I thought that I would…

Bonnie Blue Butler maneuvered through the crowded tables with an…

Debbie said she would be waiting for us at her…

We both were so stunned we sat down in the…

I didn’t sleep well that night. The pie that had…

In October, political advertisements bloom on all the signboards and…

Haley came to supper that night. Usually I try to…

My house smelled wonderful when I came back from my…

Fly McCorkle scampered agilely down a ladder propped against the…

Indian summer held on. On Saturday, Fred pushed his riding…

Fred slept like a baby that night. I think his…

I knew when I got home there would be a…

Two separate lines of storms rolled through that night. The…

We stopped again at Kentucky Fried Chicken. The restaurant was…

When Debbie left, I followed her to the porch. I…

Fred is neither a partygoer nor a party-giver. I get…

It was after midnight before we were allowed to go…

The sky was beginning to lighten when I finally fell…

The light was there at the end of the tunnel,…

M

ary Alice flung her purse on my kitchen table, where it landed with a crash, pulled a stool over to the counter and perched on it. “Perched” may not be the right word, since Mary Alice weighs two hundred and fifty pounds. The stool groaned and splayed, but it held. I began to breath again.

“I have decided,” she announced, “that I am not going gentle into that good night.”

“Thank God,” I said. “We were all worried about you. Last year when you dyed your hair Hot Tart—”

“Cinnamon Red.”

“Well, whatever. We all said, ‘There she goes gentle.’”

Mary Alice giggled. She’s sixty-five years old, but she still giggles like a young girl. And men still love it.

“That was a little much.” She patted her hair. “This

is just plain old Light Golden Blond. It’s what you ought to use, Patricia Anne.”

“Too much trouble.” The timer went off on the stove and I took out a batch of oatmeal cookies.

“It would charge Fred’s batteries.”

“There’s nothing wrong with Fred’s batteries.” I went around her to get a spatula and opened the drawer too hard, banging it against my leg. How long had it taken her to get to me this time? One minute? No record. In the sixty years we have been sisters, I figure the record is somewhere below zero, into the negative integers of time. Absolute proof of the theory of relativity.

“Well, your hair sure could use some help.”

I scooped up a hot cookie and handed it to her. Burn, baby, burn.

Mary Alice blew on the cookie. A couple of crumbs fell on her turquoise T-shirt, which declared “Tough Old Bird” and which had a pelican with a yellow beak peeking around the words. Given the expanse and jiggle of Mary Alice’s chest, that bird was having a rough flight. “Hand me a paper towel,” she said. I tore one off and gave it to her. She sank her small teeth into the cookie. “Ummm,” she said. “Ummm.”

“Good?”

“Ummm.”

I put the plate by her. “You want some tea?”

“Ummm.” She reached for a second cookie. “Mouse,” she said, “these are great.”

I banged the ice into the glasses. Mouse. The old childhood nickname.

Mary Alice looked up. “I’m sorry. It just slipped out.”

I sighed. “It doesn’t matter.”

“And mice are little and cute.”

“And can bite.”

“Yeah. I’d forgotten about that.” Mary Alice has a crescent scar on her leg where I bit her when I was three and she wouldn’t let me play with her Shirley Temple doll. Daddy had liked to tell the story and said he thought they were going to have to wait until it thundered to get me to turn loose, a reference to snapping turtles. He and Mother had called me Mouse, too, though. And say what you please, if Mary Alice and I hadn’t been born at home, I know they would have been at the hospital having the records checked to make sure we hadn’t been mixed up. Whereas Mary Alice had been born a brunette with olive skin, I had been a wispy blonde and pale. She had been healthy and boisterous; I, sickly and quiet. My big teeth should have been hers. You name it; if it could be different, it was.

“I know a woman named Jean Poole,” Mary Alice said. I smiled. We had been thinking the same thing. “What I came to tell you, though, is I’ve bought a country-western bar named the Skoot ’n’ Boot. Up Highway 78.”

I laughed and reached for a cookie.

“When Bill and I were in Branson, Missouri, last spring, we learned how to line dance, and we’ve been going out to the Skoot ’n’ Boot every Thursday night. It’s a lot of fun. You and Fred ought to try it.”

“Are you serious?”

“Of course I’m serious. Y’all don’t do enough. Fred’s only sixty-three. Bill’s seventy-two and he just loves it. He’s hardly out of breath when it’s over.” Bill Adams is Mary Alice’s current “boyfriend.” I swear that’s what she calls him. He showed up trying to sell her a supplement to her Medicare and he never really left.

“No, I mean about buying this place.”

“Sure I’m serious. I told you I wasn’t going gentle into that good night.”

“Nobody thought you were, Sister.”

“And country-western bars are hot right now. Everybody’s going to them, getting dressed up in their fringy clothes and boots.”

“Fringy clothes?”

“Stuff with fringe on it. You know.” Mary Alice stretched her fingers out from her chest as if she were pulling bubble gum from the pelican’s beak. “Fringe. Tassles.”

“Where is it, this bar?”

“The Skoot ’n’ Boot. I told you. It’s about twenty miles out Highway 78. Bill and I were in there the other night and got to talking to the man who owns it, and he said he was trying to sell it, that he needed to go back to Atlanta because both his parents are sick and he needs to be near them. He says he hates to leave because the club’s doing so well. There was a crowd out on the floor line dancing and I thought, Well, why not? Roger would have liked his money invested this way. So we met at the bank this morning and I bought it.”

Roger had been Mary Alice’s third husband. They had all died rich and, thanks to Sister, happy. She had given each of them a child, which, considering their advanced ages, was more than they had expected. And I think she really loved them—the husbands. She has them buried together at Elmwood Cemetery for convenience. She got a deal on a whole plot when the first one departed and swears they wouldn’t object. Their children, my nieces and nephew, are wonderful. And I’m sure Mary Alice is right. Roger would probably be delighted to have his money invested in the Skoot ’n’ Boot if that was what she wanted.

Mary Alice reached for another cookie. “I want you to come with me to see it.”

“Now?”

“Sure.”

“I need to get supper started. You know Fred likes to eat soon as he gets in so the food will get by his hiatal hernia before he goes to bed.”

“Give him an Ultra Slim Fast. They go down quick.”

So I wrote Fred a note that I had gone to Sister’s new country-western bar, the Skoot ’n’ Boot, and left, wishing I could see the expression on his face.

“What is line dancing, anyway?” I asked as we went out the door.

“Fun.”

October is the second most beautiful month in Alabama, the first being April, when the dogwood and redbud are blooming. Most people are surprised when they come here for the first time and see the mountains. Granted, we’re at the end of the Appalachian chain, but we have some pretty respectable mountains and beautiful color in the fall. The day Mary Alice and I set out to see the Skoot ’n’ Boot was the kind you think of when you think October. Seventy-five degrees, a cloudless sky and everything golden as buttered biscuits.

“Oh, my,” I said, leaning back and looking through the sunroof of Sister’s car at the cobalt-blue sky. I pushed my glasses up on my head and relaxed. “This is nice.”

“Absolutely.” She leaned over and got another cookie out of the plastic bag I had brought. “You know what I’ve been thinking?”

“What?”

“We can have your fortieth anniversary at the Skoot ’n’ Boot. Wouldn’t that be fun? All the kids would

come. That’ll be great. We’ll make a family reunion out of it.”

I got this mental picture of all of us dancing in some kind of conga line, with Fred leading the line.

“You know, I think Fred looks like Ross Perot when he has a short haircut.” Her mouth was full of cookie.

Again we were thinking the same thing. “Better-looking,” I said.

“We could have champagne and music, all the things you didn’t have at your wedding because of the Hollo-wells. I always thought that was real tacky. It was your wedding, after all, not theirs.”

“It was best to start off on the right foot with my in-laws.”

“What could they do? Not come visit you? Tough titty. Every time that old woman showed up, you acted like you kept a kosher kitchen.” Mary Alice blasted the horn and whirled around a pickup truck. “God, that was hard to do.”

“Pass that truck?” I looked back.

“Keep a kosher kitchen. Have you forgotten my darling Philip?”

I hadn’t. Philip Nachman, her second husband.

“Well, he insisted on a kosher kitchen.”

“You never kept a kosher kitchen.”

“I know it, but it was so hard keeping him from finding out.”

Mary Alice blew the horn again and waved at a woman at a farm stand. “I want to get some pumpkins there on the way home. You want some pumpkins for Halloween decorations?”

“Sure.”

“We could even have a renewal of your vows. A lot of people are doing that now. The minister could stand where the Swamp Creatures play and y’all could stand

on the glass boot. How does that sound, Mouse? I’ll bet you could still wear your wedding dress. How much do you weigh, anyway?”

“A hundred five.” I was beginning to feel out of breath like I always do when I’m around Mary Alice for a while. Swamp creatures? Glass boot?

“You were always anorexic.”

“I’ve never been anorexic!” I reached into the bag and put a whole cookie in my mouth. I was still chewing on it when Mary Alice pulled into the parking lot of the Skoot ’n’ Boot. It was not at all what I had expected. It looked like it had at one time been several small shops in an L-shaped building.

“They knocked the walls out,” Sister explained.

“But where’s the front door?”

“Don’t talk with your mouth full. Over there. See the sign?”

She pointed upward. On the roof, a huge boot, with “Skoot ’n’ Boot” emblazoned on the side with what looked like rhinestones, pointed its toe downward toward an arrow that said, “Enter.”

“The sun was in my eyes,” I lied. Sister is always accusing me of not seeing the obvious, and this time she was right.

She leaned back and looked at the sign with admiration. “At night it lights up. You know how the lights used to run around the front of the Alabama Theater? That’s the way these do. It really stands out at night. You can see it way down the highway. A few of the bulbs are out, though. I meant to stop by Kmart and get some. Bill said he would put them in.”

Bill? Seventy-two-year-old Bill, climbing up on the roof and then up the sign? “Mary Alice,” I said, but she was already getting out of the car.

Once out, she held up her arms like the Indian in a

picture Grandma used to have, invoking the Great Spirit or something. “Beautiful!” she said.

I am a sixty-year-old woman. I am five feet one, one hundred and five pounds, gray hair, married to the same man for forty years, mother of three, grandmother of two, sister of two-hundred-fifty-pound, five-foot-ten, golden-haired Mary Alice Tate Sullivan Nachman Crane, a sixty-five-year-old bar owner and line-dancing loony. Lord!

I climbed out of the car. “Sister,” I said, “don’t you let Bill get up on that sign.”

“He’ll be okay.” Mary Alice reached over, grabbed my shoulder and crunched me to her. “Don’t you just love it?”

“Wuump,” I said against her ample bosom.

“I just knew you would. Come on, let me show you the inside.” She let me go and I staggered a few steps while she hauled her purse up from where it hung around her knees and started looking for her keys. Sister’s purses are never ordinary purses. They are huge and have straps so long that on most women they would drag the ground. She orders them custom-made from somewhere. She can never find anything, though. I have a little hook on the inside of my purse for my keys, and I gave Sister several until I saw she wasn’t going to use them. I knew if I opened my purse right then, my keys would be on their hook, neat as anything.

She was about to empty her whole purse out on the car seat when the Skoot ’n’ Boot door opened and a man called out, “Mrs. Crane!”

Sister beamed. “Hi, Ed,” she called back. “I didn’t think you’d be here yet.” She put her purse strap back over her shoulder and grabbed me by the arm, pulling me toward the now open door. “He’s the one I bought it from,” she explained.

“Quit pulling me!” I hissed to no avail.

“Ed, this is my sister, Mrs. Hollowell. She was dying to see the place, so I brought her out.”

“How do you do, Mrs. Hollowell.” Ed greeted me with a damp, limp handshake, which surprised me, since he looked like he could be the club’s bouncer. He was in his thirties but was already beginning to bald. The white T-shirt he was wearing showed off not only his muscles but also a tattoo of a hula girl with the message “Hail Maui, full of grass” on his forearm.

He rubbed the hula girl against his sweating forehead and said we should come on in. “I’ve just been cleaning up some.”

“Well, aren’t you the sweet one.” Mary Alice swept by him. I followed her. Once inside, she did the Indian-upraised-arms thing again. “Mouse, I ask you. Is this not the most darling place you have ever set eyes on?”

I couldn’t see a thing. I stood there waiting for my eyes to adjust from the bright October sunshine. From the left came the sound of trickling water. “Is there a water leak?” I asked.

Mary Alice laughed. “That’s the wishing well. It makes you want to pee, and the more you pee, the more beer you drink. Right, Ed?”

“Right, Mrs. Crane.”

“Mary Alice!” I fussed.