My Father's Fortune (27 page)

Read My Father's Fortune Online

Authors: Michael Frayn

Or as true an account as I can manage, given the weakness for fiction that my father also left me.

*

Looking after our father in his last illness and dealing with his death bring my sister and me closer than we've been since that other death, twenty-five years earlier. In the years that follow, though, our lives begin to change. For both of us old longings and possibilities, apparently extinguished for ever in the placid waters of family life, begin to stir. We both run a little wild, and, in the devastation that follows, both our families break apart. Has our father's death snapped some last invisible link in a chain that neither of us was really aware of? My sister strongly disapproves of the new life I make. She begins speaking to Elsie again before she dies, after eleven years of silence, but refuses, out of loyalty to my first wife, to speak to my second for the next twenty-seven years.

And now, looking over her life from this new perspective, she starts to spread her disapproval back to the father whose side she had taken in the long Cold War with Elsie. âHe was a rotten father,' she says to me one day, out of the blue. I'm so surprised that I fail to ask her why she thinks this, and even now I still don't understand what the deficiencies were that she retrospectively found in him.

Whatever my sister meant by her dismissal of our father, it's true that he did play a part in leaving her and the world at large a terrible legacy. Thirty-three years after his death she begins to suffer from shortness of breath. It takes the doctors several months to diagnose the cause: mesothelioma, the incurable and deadly cancer of the lining of the lung that emerges sometimes half a century or so after exposure to asbestos, and that was first properly understood after he died, even later than the effects on the human body that my kind Uncle Sid's cigarettes were having. The only asbestos she can recall ever being exposed to was in the samples that my father used

to bring home, and that I sawed up. A hand has reached out of the remote and innocent past, just as it did from the isolation hospital where our mother had caught her childhood scarlet fever.

She's sixty-six. The doctors say she has three months to live. Her illness brings us together again, just as those two earlier deaths had. I call on her at her son's house where she has taken refuge, mistake her instructions about letting myself in round the back, and oblige her to come to the front door. It takes her many minutes; when the door at last opens she has almost no breath left in her body. Later I try, at long last, after sixty years of silence on the subject, to talk to her about our mother. I ask her if she remembers her playing the violin to us. She doesn't, and in any case the term âour mother' is still unusable between us. We don't pursue the subject. The doctors, it turns out, are wrong about her having only three months to live. She has one.

I may yet go the same way myself; no one knows how long that hand out of the past can sometimes be stayed. In the meantime I've become older than my father was when he died. Six years older â I'm on my way to becoming

his

father. If I'm making fun of him in this account of his life â his ridiculous hopes of my sporting abilities, the lightness of his tread upon the earth, his deafness, his âguv'nor' and his âhotchamachacha' â it's rather in the way that he made fun of me for so many things â rather in the way that a lot of sons and daughters seem to make fun of their father when they get around to writing about him, as they so often do in later life.

Whether he in the end felt proud of me or not, I'm certainly proud of being his son. The joshing is the way I've inherited from him of expressing my pride. Yes, and my love, that I never found the occasion to mention to him. Unlike the sons of Noah, I have impiously uncovered his nakedness. I have, though, tried to emulate another mythical son; I have borne him as best I could out of the ashes of the past in the way that the pious Aeneas bore his father Anchises on his back out of the ashes of Troy, in those pages of Virgil that fluttered away in the wind so many years ago.

*

He sometimes opens his eyes for a moment, when I visit him in the hospice where the last five weeks of his life ebb away, and gives me a smile, but he can no longer speak, and for most of the time he seems to be asleep. It's as if he has faded, like the Cheshire Cat, until only the smile remains. Behind his closed eyes his wrecked brain must still be partially functioning. Is some kind of conscious inner world continuing? What are his last experiences in life? A shifting, tangled dream, perhaps, of lions and discomfort; of rainwater goods and the warmth of the car on a summer's day; of duck eggs and tramlines. Perhaps for a moment he's back in Devonshire Road, throwing the bread under the table and eating the cheese. Or walking into the party and seeing Vi again for that first time. Or perhaps there's only confusion and strangeness.

What's going on in

my

head, as I sit there at his bedside? Nothing worthy of the occasion, so far as I can recall. Thoughts about my work. Wondering how long I should stay. Occasional pangs of helpless grief. Mostly, I think, longing for him to die, for both our sakes, and for it all to be over.

It happens at four-thirty in the morning, on 9 May 1970. I'm not with him. The last of him for me was when I visited him the previous evening. He can't open his eyes any more. I take his hand, as I did Nanny's, and tell him who I am. I feel a faint pressure on my hand in return.

Then he smiles. His old familiar smile, all that's left of him, for one last time.

Slowly the smile fades.

And that's the end of the story.

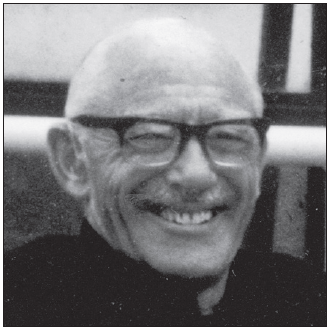

Michael Frayn was born in London in 1933 and began his career as a journalist on the

Guardian

and the

Observer

. His novels include

Towards the End of the Morning

,

The Trick of It

and

A Landing on the Sun

.

Headlong

(1999) was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, while his most recent novel,

Spies

(2002), won the Whitbread Novel Award. His fifteen plays range from

Noises Off

to

Copenhagen

and most recently

Afterlife

. He is married to the writer Claire Tomalin.

Â

fiction

The Tin Men

The Russian Interpreter

Towards the End of the Morning

A Very Private Life

Sweet Dreams

The Trick of It

A Landing on the Sun

Now You Know

Headlong

Spies

Â

plays

The Two of Us

Alphabetical Order

Donkeys' Years

Clouds

Balmoral

Make and Break

Noises Off

Benefactors

Look Look

Here

Now You Know

Copenhagen

Alarms & Excursions

Democracy

Afterlife

Â

translations

The Seagull (Chekhov)

Uncle Vanya (Chekhov)

Three Sisters (Chekhov)

The Cherry Orchard (Chekhov)

The Sneeze (Chekhov)

Wild Honey (Chekhov)

The Fruits of Enlightenment (Tolstoy)

Exchange (Trifonov)

Number One (Anouilh)

Â

film and television

Clockwise

First and Last

Remember Me?

Â

non-fiction

Â

Constructions

Celia's Secret: An Investigation

(with David Burke)

The Human Touch

Collected Columns

Stage Directions

Travels with a Typewriter

First published in 2010

by Faber and Faber Ltd

Bloomsbury House

74â77 Great Russell Street

London WC1B 3DA

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© Michael Frayn, 2010

The right of Michael Frayn to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

ISBN 978â0â571â27060â6