My Guantanamo Diary (5 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

The doctor often stared for hours at the neat handwriting of his little girl. This letter was a gift; it made it through the censors in good shape. He ran his fingers across the folds and creases of the small pages. The sentences filled the margins vertically, not wasting any precious space. He was unable to read much of many of his daughter’s letters because they were redacted by the military, forcing him to imagine what was written beneath those thick blocks of black ink where something had been marked out. What could a ten-year-old child have written to her father that could pose a threat to U.S. national security?

One Arab detainee complained to his attorneys that his daughter’s letters were also being constantly censored. The lawyers, curious as to what the military found so sensitive in a little girl’s messages, called the detainee’s family and found out. Knowing that the detainee’s children were his weak spot, the censors were blacking out every “I love you” or “I miss you” that the child had written.

Once in a while, Mousovi would look at the photographs his family sent. Family photographs are gold at Guantánamo Bay, but they, too, must go through a process of military review and clearance. The military checks for encoded messages. Once the photos are cleared, they are stamped and given to the detainees.

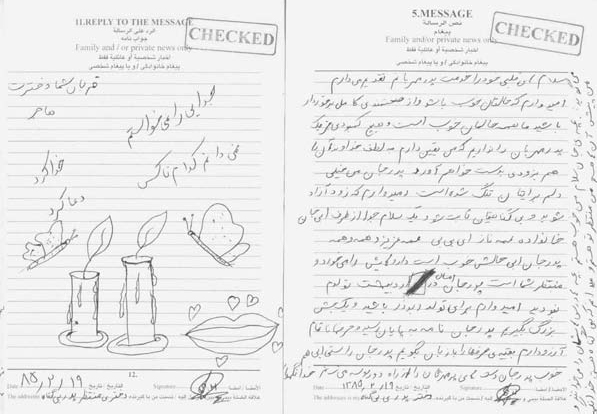

Hajar’s letter to her father.

Courtesy of Dr. Ali Shah.

Family pictures, though, made the doctor sad. Despite the family’s reassurances that all were doing fine, that there was nothing to worry about, he grew listless over the years, worrying about his wife and about his children growing up without a father. Every time he received another picture, the children looked different. And he worried about living to see his seventy-nine-year-old mother again. Sometimes he wondered whether she was alive or dead.

Peter, Mousovi, and I discussed various strategies that could help his case. We talked about contacting witnesses in Afghanistan and collecting evidence to support his defense.

Then, Mousovi asked about news from Afghanistan. Was it peaceful? Was there fighting? Were the Taliban gone for good? Who had been elected to the Afghan parliament?

Military rules allowed lawyers to discuss political news with their clients only if it was somehow related to their cases. So, Peter could only respond with some vague answers about what the U.S. media were reporting about the political climate in Afghanistan. Mousovi seemed a bit disappointed, but he didn’t press.

Just then, a guard knocked on the door, signaling that our time was up. The doctor quickly signed a document agreeing to have Peter represent him in filing a petition for habeas corpus before U.S. civilian courts. He asked us to return soon and to write and keep him updated on his case. But he remained hopeful that he would be freed before we would have a chance to visit him again. If, “Inshallah—God willing” that happened, he said, his door would always be open to us, and we would have to visit him in Afghanistan, where we would be his honored guests.

“I pray to Allah,” he said, holding his open palms together, “for

sabar

—patience.” “Please remember me in your prayers, my sister, and ask your mother to pray for me too.” He stood up, a gesture of respect, as Peter and I said goodbye. When I glanced back after we walked out, he was still standing, gazing after us.

I don’t know exactly what I had expected coming to Guan-tánamo Bay, but it certainly wasn’t that weary, sorrowful man.

As our guard led us out of Camp Echo, I pulled the heavy shawl off my head and thought about everything he had told us and of the long years he had spent in confinement without ever being charged. “I’ve been duped,” I thought. “My government has duped me.”

GETTING THERE

The journey to Guantánamo begins at the commuter terminal of the Ft. Lauderdale/Hollywood International Airport. With the exception of one corporate law firm that always makes a grand entrance in a chartered private jet, the attorneys doing habeas work at Gitmo fly one of two commercial airlines, Air Lynx or Air Sunshine.

At the counter, you’re asked to show clearance documentation provided by the Department of Defense. Then, you hop onto the luggage scale because seating on the tiny puddle jumper prop planes is determined by body weight. The ten-seat cabin is so small that it’s impossible to stand fully upright. Before boarding, everyone hits the bathroom because there aren’t any lavatories on board. Some people bring earplugs or large headphones in a futile attempt to drown out the noise of the engines.

Surprisingly, we don’t have to go through any kind of security procedures before boarding. There are no metal detectors

to walk through and no X-ray machines to scan our baggage. Nor does anyone bother to open our checked luggage.

“Why don’t you guys look through our bags?” I asked one of the Air Sunshine workers on an early trip.

They used to, he replied, “but sometimes people pack dirty laundry, and I don’t want to touch that stuff.”

In preparation for takeoff, the copilot stands with his neck craned sideways to avoid hitting his head against the cabin roof while giving safety instructions. “Ladies and gentlemen, welcome aboard Air Sunshine, nonstop to Guantánamo Bay,” he says. “Life vests are under your seats. Help yourselves to plenty of drinks.” He points at a red plastic cooler in the middle of the aisle filled with an obscure grape-flavored soda called Faygo.

On my first trip, I started looking around for my life jacket and frantically told Peter that I couldn’t find it. He laughed.

“Don’t worry. If this plane goes down, your life vest isn’t going to do you any good,” he said.

That

was reassuring.

The flying experience itself is a little dodgy, and there’s almost always some sort of drama. On one flight, we had no copilot, and I prayed all the way down that the pilot didn’t have any history of heart disease in his family. Once, a big brown cockroach joined us on the flight and crawled up an attorney’s leg. She screamed. So did I. When the bug started flying around the cabin, I think the weight distribution was definitely altered.

The lack of lavatories on the planes often leads to some dicey situations. Even though Cuba is only ninety miles from the mainland, the flight takes three hours because the plane

has to go all the way around the island to avoid Cuban airspace. Air Lynx used to carry bags of sand for passengers to use for relief but eventually stopped because none of the passengers seemed to know what they were for. Occasionally, some attorneys use an empty Coke bottle if they’re desperate.

That’s not a terrible arrangement for a man, but it doesn’t work quite so well for a woman. On one trip back to Florida, a female paralegal tapped my shoulder just forty minutes into the flight.

“What do I do if I need to go to the bathroom?” she asked with a look of discomfort on her face.

“You hold it,” I advised.

“Well, what about in the case of an emergency?” she asked. I tried to think creatively because she looked really uncomfortable, and a Coke bottle wasn’t going to do the trick.

“You could use the drink cooler,” I suggested seriously. I could tell that she was starting to panic.

“Do they ever land the plane early?” she asked.

“There’s nowhere to land. We’re over the middle of the ocean.”

She hobbled back to her seat, but ten minutes later she was hovering above me again. She stuck her head past the curtain that separated the cockpit from the cabin and told the pilot, a woman, about her dilemma.

Without a word, the pilot handed her an empty Snapple bottle and asked the passengers at the rear of the plane to move forward.

“I’m so embarrassed,” the paralegal said, turning crimson.

The pilot, though, was unfazed. “Don’t worry about it,” she said. “Once someone went No. 2 in the middle of the aisle.” She held up two fingers.

The paralegal looked horrified. “What did you do?” she asked.

“I put on my oxygen mask and flew the plane.”

We feel lucky when the flights are uneventful because no one likes incidents on airplanes. One time, all the passengers were pulled off the plane because the engine wouldn’t start. We sat around on the Gitmo tarmac for a half-hour waiting for a jump start. It’s also not uncommon for an overweight passenger to break one of the twenty-year-old seats, forcing us back out onto the tarmac while a spare is brought in. Once, during a stormy night flight, the plane dropped several hundred feet. Screaming passengers hit their heads on the low cabin ceilings, and belongings went flying.

The worst thing, though, is when the plane leaves early from Cuba. On a few occasions, the Iranian Air Sunshine pilots— there are three who rotate, Farshad, “John,” and Mohammad— have decided to leave Guantánamo Bay before the scheduled departure time. They are a lovely bunch, but why they think this is okay, I don’t know. Lawyers have arrived on time only to see their plane disappearing off down the runway.

Upon arrival, we’re greeted by armed U.S. Army personnel who direct us to customs, which consists of a couple of brown tables where more Army boys rifle through our bags.

The base is divided into two areas, the leeward side and the windward side, by the two-and-a-half-mile-wide Guantánamo Bay. The main base is on the windward side, which is where the detention camps are built. There are nine camps (of which we are presently aware) named 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, Echo, and Iguana. Each numbered camp is subdivided into several blocks

with alphabetical names: Alpha, Bravo, Charley, Delta, Echo. There’s also India, Tango, Romeo, Whiskey, Foxtrot, and Zulu.

1

Camps 1, 2, and 3 consist of rows of adjacent steel-mesh cages with one man per cage. Camp 4 is a medium-security prison for “compliant” detainees and houses up to ten men per room. They are allowed to watch nature films, sports, or prescreened movies once a week. Camp 4 prisoners are also allowed to pray and eat communally, and they have greater access to reading material, an exercise bike, and a soccer ball. Many show up to attorney meetings with broken or injured toes because they play soccer in flip-flops.

2

Once Camps 5 and 6 were built—these contain solitary-confinement cells—many prisoners were transferred there from Camps 1, 2, and 3. Camp 7 holds the fifteen high-value detainees and is run by a special military unit, code-named Task Force Platinum. I have met mostly Afghans in Camp Echo, which is used for habeas meetings (and other classified activities). Sometimes meetings also take place in Camps 5 and 6 and Iguana.

3

Habeas counsel are lodged on the leeward side at the Combined Bachelors Quarters (CBQ) for $20 a day. It provides cable TV, a phone, dial-up Internet, a small kitchen, and maid service. Strangely, each room has four twin beds. On my first trip, I debated whether to sleep in a different bed each night.

For several months, some rooms were under renovation, so the attorneys were lodged two and three together. That led to some gossip about whose snoring sounded most like that of a dying animal.

In the early summer months, it rains, and that caused another problem. Hundreds of orange crabs would take cover in

our rooms. I freaked when I saw the creatures rushing under my door. I ran out immediately to ask for a room on the second floor. Attorney Carolyn Welshhans of Dechert’s Washington, D.C., office was more valiant. She took to smashing the ugly things with a metal trash can.

Gitmo is a strange place, but you find yourself conforming quickly to its clockwork military rhythm. Every day begins at 7:30 AM. It’s almost always bright and sunny. The Jamaican gardener, William Bartley, holds the garden hose with one hand and waves at visitors with the other, laughing and addressing us at the top of his lungs with the Jamaican term of endearment, “Hello, my Dods!”

We smile and wave back.

“Hi, Bartley!”

Everyone at Gitmo seems to have a story. Sometimes, when I had downtime in the evenings, I would wander off to the Clipper Club, the local greasy spoon, and chat up the Jamaicans who made me pizza and deep-fried hot dogs and chicken strips. The place was usually dead, and the guy behind the counter would happily chat away while intermittently commenting on the

American Idol

contestants. He had five children with five different women. At one point, one of the women was threatening to tell his wife about their child. She was blackmailing him for gifts and money. I was amused but tried to give him advice as I ate his fried chicken fingers, fried cheese sticks, or something else equally deep-fried.

The CBQ desk workers were exceedingly polite Filipinos who wore Hawaiian shirts, as if we were checking into a Maui resort. All of them earned well below minimum wage, but they said it was still better than the jobs back home. At night,

they would log into their accounts on

Myspace.com

and chat with friends in the Philippines or watch TV in the lobby.

In the morning, we all meet at the concrete circular tables at the front of the CBQ to wait for the bus, which leaves at exactly 7:41 AM. It pulls up to the dock at 7:51 AM, just as the ferry that will take us to the windward side is arriving.

At exactly 8:20 AM, we’re dropped off on the other side, where a military escort greets us and hands out our habeas badges. Next stop is Starbucks and the food court to have breakfast and pick up food for the detainees. Then, on to Camp Echo, where meetings with detainees are held.

The only part of the Gitmo experience that doesn’t run with military precision is the counsel meetings themselves. More often than not, there’s a delay in bringing the prisoners over to Camp Echo. Once, we had to wait five hours on the bus. Naturally, this frustrates the attorneys, considering the time, money, and weeks of work they’ve spent preparing. And the ice cream we’ve brought turns to soup.

At the end of our visit with Ali Shah Mousovi, our military escort drove Peter and me and another group of attorneys to the Navy Exchange. Adjacent to this large supermarket are a Subway, a gift shop, and ATM machines. Across the street are a KFC and a McDonald’s. At the exchange, we picked up a stack of porterhouse steaks, charcoal, potatoes, chips, lots of beer, and assorted wines. Everyone barbecues for dinner because,

unless you head for the Clipper Club, there’s nowhere and nothing to eat on the leeward side.

Over a steak dinner that night, I commented on how nice our military escorts were, that they joked and laughed with us. One of them had given me pointers on pool in the CBQ lobby. Everyone brought them beer and cigarettes. I had expected them to be more aloof, even hostile.