My Name is Number 4 (19 page)

Read My Name is Number 4 Online

Authors: Ting-Xing Ye

I was so scared I couldn’t sleep that night, and the next morning, Yu Hua tried to console me, but failed. Then she brightened. “Xiao Ye, I have an idea. Let’s go to the sub-farm administrative office and get this cleared up. Cui and Zhao are low level, after all. They shouldn’t be interfering in this matter.”

Once again I was grateful for my friend’s clear head. After we hurried to finish our quota of new paddy dikes, we asked Jia-ying to fetch our supper for us and keep it in the dorm, then headed for the sub-farm. By the time we arrived, it was dark. My heart fell when I saw the office was closed for the day.

“Don’t give up,” Yu Hua urged. “Maybe they’re having supper.”

We found the canteen and, after questioning a number of people, were directed toward a tall, middle-aged man eating alone at one of the tables. PLA representative Huang, who was army, not air force, had a kindly face and large, intelligent eyes. Hearing the reason for our visit, he led us to his office.

His accent placed him from Zhejiang Province. He invited us to sit down, and his politeness gave me confidence. I omitted my original request to delay my

tan-qin

until July. I explained my concern that the reps might not allow me to go home at all. Representative Huang took out his copy of the farm personnel registration book, leafed through it, turned it toward me, and asked me to point out my name. I did so, with a shaking finger. He read the information about my family, then closed the book and looked up.

“There will be no problem,” he said. He went on to explain that the government policy applied to everyone. As he spoke, an angry edge crept into his voice. “It is tragic enough that you lost both your parents. How could those two—” and he stopped himself.

On our way back to our village, we met Xiao Zhu, Xiao Qian and Xiao Jian, three male friends of Yu Hua. Zhu and

Qian were the ones who had helped during my attack of appendicitis, and all three of them, along with Yu Hua, had visited me in the hospital. I had always appreciated their friendliness. Like Yu Hua, they were all older than me, but despite their correct political backgrounds, none of them looked down on me.

Xiao Jian—the young assistant accountant—suggested we all go to his tiny office next to the canteen where he could heat up our supper. While I ate, I talked and laughed, happy that my problem had been solved and delighting in their camaraderie.

The next evening Yu Hua and I were summoned to Cui and Zhao’s office. As soon as we entered, Zhao began to shout at us.

“How dare you two play tricks behind our backs!” he screamed, his face red with anger. “How dare you go over our heads!”

Swearing and cursing, his cap crooked on his head, he accused us of trying to undermine the PLA. When we tried to speak he cut us off, became angrier, screamed louder. Cui sat at his desk playing with a pencil, not saying a word through the entire tirade, until he finally dismissed us with a wave of his hand.

“Screw your mothers!” Zhao shouted as we left. “Screw both of them!”

We slunk away. I had no idea what kind of a mistake we had made, but when I boarded the ship for Shanghai a week later, my heart was full of foreboding. I knew I had not heard the last from Cui and Zhao.

The dock at Shanghai Number 16 Pier was awash in people. Shouts of joy swirled around me as my farm-mates threw themselves into the arms of weeping mothers and fathers. No one from my family was there to greet me. Great-Aunt, now almost sixty, was too old to fight the crowds; on her three-inch lily feet she would have been thrown off balance and trampled in no time. Number 1’s and Number 5’s

tan-qin

did not coincide with mine. Number 2 would be home soon, but this day he was digging air-raid shelters in the suburbs with his fellow workers. Number 3 couldn’t get to the city until Sunday, her day off.

Since I knew I would find the apartment that once rang with the noise and bustle of eight people empty and quiet, I was in no hurry to get home. I also knew that as soon as I walked in the door I would start to pretend, for I couldn’t burden anyone with my true experiences and loneliness on the farm. I stood in the cold February rain waiting for my bus.

Number 3’s arrival in Purple Sunshine Lane lifted my heart.

“Ah Si, you look wonderful,” she exclaimed as soon as she came in the door. “The last time I saw you, you were as thin as a stick!”

A pretty young woman, now nineteen, she lived in a one-room factory dorm with three other unmarried female workers—not an ideal arrangement, but her job meant she

was secure from assignment to the countryside and could think about settling down.

Over tea prepared by Great-Aunt, we chatted happily.

“I haven’t found a boyfriend yet, but I’ve got my eye open,” Number 3 joked. “Look,” she added proudly, handing me a photograph that showed her in an army uniform, a gun slung over her shoulder.

“You’re in the militia?” I asked, passing the photo to Great-Aunt.

“I’m a leader!”

“By the time Number 3 gets around to pointing her gun,” Great-Aunt put in caustically, “the Russians will have taken over the factory.”

“I’m surprised they accepted the daughter of a capitalist,” I said.

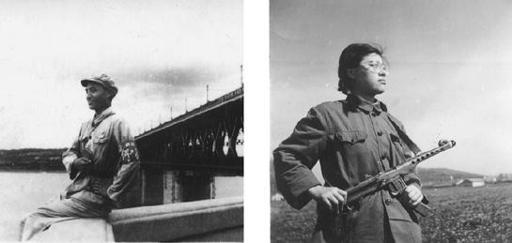

(Left) Number 1 disguised as a Red Guard in the “Great Travels,” 1966, in front of the Yangtze River Bridge in Wuhan

.

(Right) Number 3, an enthusiastic member of her factory militia, in Songjiang County, 1969

.

Number 1 (with clarinet) rehearsing with the Spreading Mao Ze-dong Thought Band, 1966

.

“Oh, they don’t care. I don’t give them any trouble. Eat, sleep and work, that’s my motto.”

A few days later, when I told Number 2 about almost having had my

tan-qin

taken away, he explained the new political climate to me, and some of the strange things on the farm began to make sense. When Mao had ordered the PLA into the work units to stabilize them against further upheavals and civil strife, the plan had been to establish “three-in-one” authority, composed of representatives from the masses, the Party officials and the PLA. Since then the PLA had accumulated more and more authority in farms, factories and bureaucracies, and once this power was firmly established, it had launched a purge of those who were against its involvement. The strongest

anti-PLA voices came from universities and academic institutes; consequently, a “counterrevolutionary” group was “discovered” at the famous Fudan University in Shanghai. A wide-ranging witch-hunt followed.

This situation was further complicated, as I learned many years later, because Lin Biao had long been quietly preparing to overthrow Mao and take over the country. In total control of the air force and much of the rest of the armed services, Lin Biao was putting men loyal to him into key positions. When the time was right, he planned to assassinate Mao Ze-dong and take power. In retrospect, the reason for the new road on our farm became clear. The road was not there to prepare for a Russian invasion at all; it was there in case of civil war, to support a possible retreat of Lin Biao’s forces.

None of us then knew of Lin Biao’s plot. All Number 2 understood was that the PLA had achieved new power in China and was ferreting out all opposition. He warned me to steer clear of any conflict, particularly where the PLA reps were concerned.

Neither he nor I knew the full significance of my visit with Yu Hua to see Representative Huang at the sub-farm, nor of his intervention on my behalf. The sub-farm administration office was, like all units, assigned PLA representatives: that was Huang’s function. But the sub-farm PLA reps were from the Shanghai Garrison, which in turn was controlled by the Nanjing Military Region, a force loyal to Chairman Mao, and therefore hostile to Lin Biao. Thus, by going over Cui’s and Zhao’s heads, Yu Hua and I had gone to their enemy.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

T

he evening after my return to the farm at the beginning of March, an urgent meeting was called in the warehouse. We were instructed not to bring our pens, notebooks and stools—an unprecedented announcement that made me nervous. In those days anything out of the ordinary was a bad omen, and Yu Hua and I were already in the reps’ bad books.

The warehouse was festooned with political slogans. “Never Forget the Class Struggle!” “Forgetting Means Betrayal!” “Long Live the People’s Liberation Army!” “We Will Smash the Heads of Anyone Who Dares to Oppose the Army!” I was well used to the strident tone of posters, but this last seemed unusually threatening.

Once inside the cold, damp warehouse, we were directed to sit on the freezing cement floor, not to squat on our heels. Cui

was in his glory. Fist in the air, he led the recitation of Chairman Mao’s slogan, “Grasp class struggle and all problems can be solved!” It grew louder with each repetition. As the room boomed and echoed with the well-worn words, two white-clad canteen staff walked slowly to the front, a huge wok held between them. Ceremoniously, they placed the wok on the ground at Cui’s feet.

Cui motioned for silence, tugged at the tails of his jacket, and began to speak. “Representative Zhao and I feel that there is a lack of class-struggle consciousness in our brigade. Chairman Mao has taught us that the class struggle must continue! In order to carry the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution through to the end, it is necessary for all of us to be reminded of the proletariat’s hardships before Liberation.”