Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960 (6 page)

Read Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960 Online

Authors: William Boyd

Georges Braque was seventy-eight years old at the time of Tate’s visit, and, along with Picasso and Matisse, one of the three great pillars of twentieth-century art. Braque, a serene, modest and genial character, was at the height of his mature powers, his great sequence of studio interiors – a chain of masterworks created over two decades and almost unrivalled in modern painting – recently completed.

Georges Braque,

La Terrasse

, 1948–61, oil on canvas, 97 × 130. Private Collection

According to Janet Felzer, Nat felt vastly more at ease with Braque than with Picasso and gladly accepted when Braque offered to show him around his studio. Braque was then reworking his painting

La Terrasse

, which he had begun some eleven years earlier, a fact that Tate found astonishing, not to say incomprehensible. He was also deeply moved and captivated by some of the smaller elongated landscapes and seascapes in the studio. Apparently Tate ventured the opinion that they reminded him of van Gogh’s late landscapes. After gently correcting Tate’s pronunciation (‘

Van Go? Non, mon ami, jamais

’), Braque commented that he ‘regarded van Gogh as a great painter of night.’ The observation seemed to trouble Nat unduly, as if it was prophetic or gnomic in some sinister way (he reiterated it to both Felzer and Mountstuart). There is a photograph of the

fête champêtre

that Nat and Barkasian had with Braque and his family and friends during that visit, taken by Barkasian, one assumes, as he is absent from the picture. Braque himself sits at the centre of the table, dappled with autumn sunshine, while the women of the household fuss over the food and the

placement

. Nat stands close to the master, on his left, a plate in his hand, almost as if he is about to serve him. But his gaze is unfocused, he looks out of frame, at something in the middle distance, or perhaps just lost in his darkening thoughts. Nothing would ever be the same again.

The

fête champêtre

at Varengeville, September 1959. Georges Braque (seated centre), Nat Tate (standing to Braque’s left), Mme. Braque (standing, pointing)

Indeed, shortly after the visit to Varengeville, the trip to France was abruptly curtailed, the Italian segment was cancelled and Tate and Barkasian returned immediately to New York.

Logan Mountstuart’s journal:

December 4th. Nat Tate came round, unannounced, last night – not drunk, indeed quite calm and composed. He offered me $6000 for my two paintings which I declined. He said he wanted to rework them (inspired, apparently, by a visit to Braque’s studio) and so I let him take them away, with some reluctance. He offered me $1500 for my three

Bridge

drawings – I said I would swop them for another painting. He became rather tetchy at this point – banging on about true artistic integrity and its conspicuous absence in NY etc etc – so I gave him a stiff drink and unhooked my two canvases from the wall, keen to see the back of him. Janet called later with a report of the same ‘reworking’ notion. She had given him back whatever work she had at the gallery. She thought it sounded a ‘neat’ idea.

Neither Mountstuart nor Felzer was ever to see Nat Tate, nor their paintings, again.

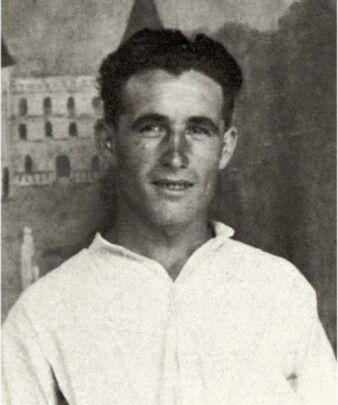

Janet Felzer, 1975

Reconstructing the last days of Nat Tate’s life is problematic, but Janet Felzer made real efforts, seeking some explanation for the events that followed

6

, which she communicated to Mountstuart, who duly noted the details in his journal.

Throughout December 1959 it is clear that Nat Tate tried either to buy back or asked to be allowed to ‘rework’ as many as possible of his paintings as were in public hands. There is no reason to doubt that he was sincere in this regard, that it was not, in Mountstuart’s uncharitable words, ‘little short of theft’. Nat Tate had seen Braque at work, had witnessed his tireless and dogged perfectionism at first hand, and it is entirely conceivable he was inspired by Braque’s example. In any event, he locked himself away in his Windrose studio and worked uninterrupted through the holiday season and into the early days of 1960. The only people to see him at this stage were Peter and Irina Barkasian and the Windrose staff.

Something, though, went seriously wrong, either with the work, or else the heavy drinking took its toll (Tate was never a serious drug user), or else the long anticipated nervous breakdown arrived. In early January, while Peter Barkasian and Irina were away in Florida, he removed all his work from the studio, the house and the strongroom and, with the enthusiastic help of the janitor and his twelve-year-old son, burnt everything during the freezing afternoon of January 8th.

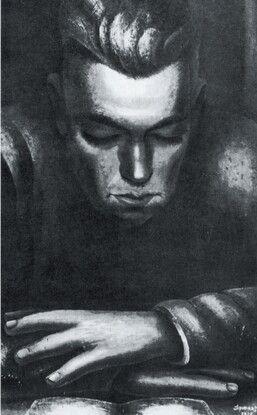

Todd Heuber, 1957

On January 10th he came to Manhattan and undertook a similar purge on the canvases in the 22nd Street studio, including, it is assumed, those he had taken from the Felzer Gallery, and Mountstuart’s two. With the slate wiped clean Nat embarked afresh, it is thought, beginning work on a new painting he entitled

Orizaba/Return to Union Beach

.

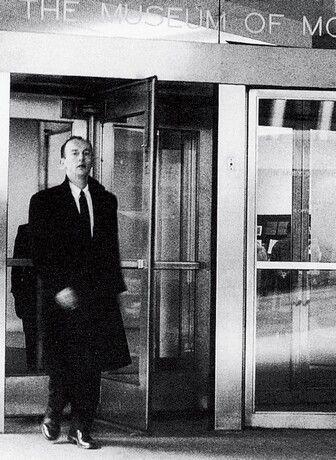

On January 12th he called on Janet Felzer at the gallery but (to her eternal regret) she was out to lunch. He went downtown to the Museum of Modern Art and had coffee with Frank O’Hara and Todd Heuber who had also, coincidentally, dropped by. Heuber had recently returned from a trip to Scandinavia and he recalled Tate talking vaguely about going back to France and visiting Braque again. Tate only stayed about twenty minutes, O’Hara remembered, and he seemed in a composed though somewhat thoughtful mood – certainly there was nothing in his demeanour to cause alarm.

Frank O’Hara leaving the Museum of Modern Art, January 1960

However, sometime after lunch Nat Tate bought a ticket on the Staten Island ferry. On board the ferry, a few moments before five o’clock that afternoon, a young man was observed to remove his tweed coat, hat and scarf, and walk to the stern. The ship was midway between the Statue of Liberty and the Military Ocean Terminal at Bayonne, heading for the New Jersey shore and roughly in the direction of Union Beach, where, theoretically, it had all begun. The young man climbed the guard rail, heedless of the other passengers’ cries, spread his arms and leaped.

Nat Tate’s body was never found. When news of the suicide and the circumstantial evidence – descriptions tallying, a taxi driver recalling a fare from MoMA to the ferry terminal, etc. – were collated the awful and depressing conclusions were reluctantly drawn. On the 15th January Logan Mountstuart and Jane Felzer went to Tate’s 22nd Street studio only to find Peter Barkasian already there supervising the packing up of Nat’s possessions.