Native Seattle (37 page)

Except where noted, the information in this atlas comes from the original Waterman and Harrington materials, the field notes and plat maps of the General Land Office's cadastral survey conducted in the 1850s, a list of villages and longhouses that was an exhibit in a 1920s land claims case, and Erna Gunther's classic

Ethnobotany of Western Washington

. Unless noted otherwise, archaeological data come from the database held and maintained by the University of Washington's Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. In many cases, additional information about the history of specific sites can be found within the main text of the book.

4

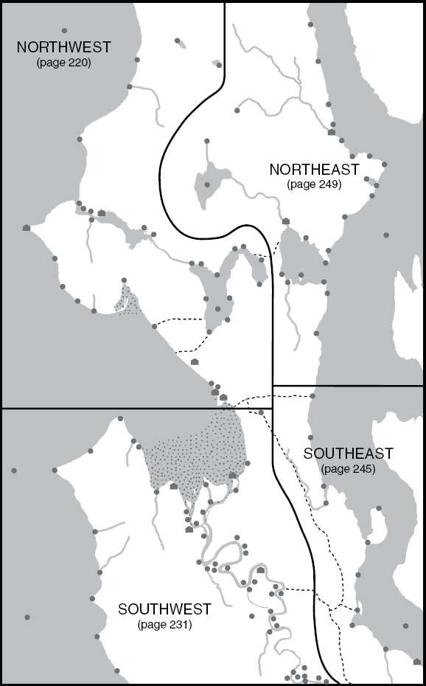

We have chosen somewhat arbitrarily to limit the scope of the atlas to Seattle's current boundaries, with a handful of exceptions in which a site immediately outside the city limits was important to understanding places within Seattle (e.g., entries 82–89) or where a site spoke directly to the broader themes of this book (e.g., entry 127).

The concerns of present-day tribal peoples dictate how this atlas should be used. Despite the tumult of regrades and ship canals, artifacts of Seattle's indigenous past surely remain undisturbed throughout the city. With that in mind, the maps have been created at a scale

that prevents the specific location of individual sites. We have also withheld mention of ancestral burial sites or of indigenous remains that have been found in the city. But should a reader inadvertently unearth something (or someone) while digging a basement or clearing brush, a call to the tribes or to the Burke Museum should be the first response—not just because it is the right thing to do but because it is in keeping with any number of state and federal laws. Finally, although many elders once said that sacred sites in Seattle had lost their power due to urban development, some are being used again today and should be treated with respect. Just as this is not a pot hunter's or grave robber's guide to Seattle, it is also not a primer for playing Indian in the city.

Maps are risky things. Publishing this information lays bare traditional knowledge, and in doing so, risks intrusion upon the intellectual and cultural rights of modern tribal people. But there is also another kind of risk: getting the history wrong. The tighter the geographical focus, the less clear the information tends to be; the result is an atlas that includes conjecture, speculation, and goings-out on various limbs in the interest of imagining the possibilities. Of course, the simple fact that in many cases this geography is speculative—the untranslatable words, the mysterious meanings, the unclear uses of places—is a result of the history described in this book; it is part of the historical silence created by epidemics, dispossession, and forced assimilation.

Waterman himself fretted about how much had already been lost when he was collecting the place-names nearly a century ago: “On Puget Sound alone, there seem to have been in the neighborhood of ten thousand proper names. I have secured about half this number, the remainder having passed out of memory. I am continually warned by Indians that they give me for my maps only a small part of the total number which

once

was used. The rest they have either forgotten or never heard. ‘The old people could have told you all’ is the remark most commonly heard.”

5

The math is off—Waterman and his students collected less than 10 percent of the names he claimed must have existed—but the point stands. So much was lost prior to the 1910s that we are bereft: the view offered by Waterman's informants looks out on only a tiny fraction of the richness that was once here. Considering the power of what we do

have, the reality must have been staggering. Instead of just over ten dozen names for Seattle, we might have had a thousand if only history had worked out differently. That said, the maps that follow are not intended as a complete or comprehensive survey of Seattle's indigenous geography; rather, they are mere glimpses of what was here before.

The final risk of maps such as these is that they might give the impression that such geographies were static and unchanging. This was surely not the case, especially in a geologically, ecologically, and culturally dynamic place such as Puget Sound. Even before the arrival of the Denny Party and others, the indigenous maps of this place surely changed over time as sites and their uses changed. Instead of a stable “zero datum” on which the rest of Seattle's history takes place, it is perhaps more accurate to think of this atlas as merely a partial snapshot of the indigenous world just prior to white settlement. It is also useful to consider the other maps that could be made to represent Seattle's diverse Native pasts: the locations of mixed-race and Indian families in Seattle's neighborhoods, the installations of totem poles in the city, and the geographies of Skid Road. Each of these landscapes could—and perhaps should—be mapped as well and interleaved with the maps presented here for an even fuller accounting of the erasures, ironies, and persistences that make up the palimpsest that is Seattle's history. I hope these maps are a step in that direction.

Linguistic Introduction, by Nile Thompson

How a given community defines its landscape through place-names has long held a fascination for many anthropologists. The vocabulary used as such is viewed as a window for understanding how a given society defines its place in the world. Certainly, traditional names have more appeal than today's urban nomenclature such as “the Seattle Center” or “Sixty-third Street.”

The place-names of the Puget Sound Salish peoples have a wide range of reference, from myth to human activity, from spirit power to animal species, and from natural resource to natural landmark. A site could

be named in isolation or it could be contrasted with other like features. The place-names themselves can refer to broad expanses or areas or to specific sandspits or rocks. Along the coastline, places were generally named from the perspective of looking toward the shore from Puget Sound.

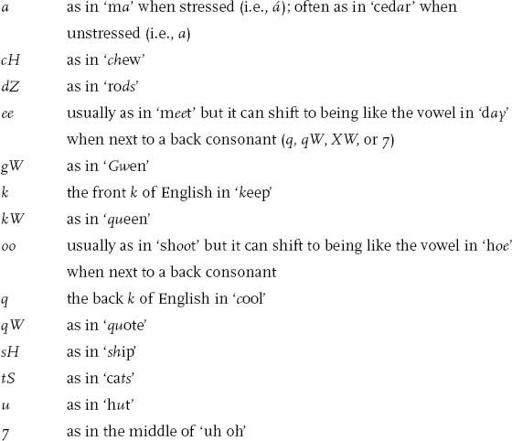

The following Whulshootseed place-names are written in a practical alphabet designed to be part of a writing system for use by speakers of English.

6

A number of the sounds of Whulshootseed are found in English and are written the same, for example,

b

,

d

,

g

,

h

,

j

,

l

,

p

,

s

,

t

,

w

, and

y

. Other sounds are specific to certain usages in English or are combination letters, composed of two parts like their counterparts in English.

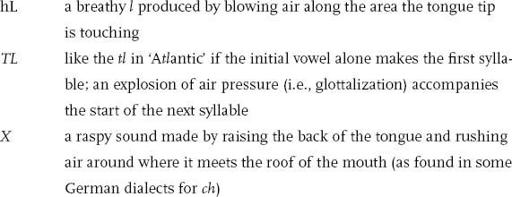

In addition to not using the Czech and Greek letters found in technical linguistic alphabets, this practical alphabet makes use of capitalization rather than apostrophes to show glottalization. Most glottalized sounds (

B

,

CH

,

D

,

K

,

KW

,

L

,

P

,

Q

,

QW

,

TS

,

W

, and

Y

) are the same as their

nonglottalized counterparts except that they are pronounced with an explosion of pressure built up at the back of the mouth. A few of the remaining sounds require a bit more explanation:

The

s

- prefix in a number of place-names (e.g., 16, 19, 20, 22, and 23) merely signifies that the word is a noun. Other prefixes are used when the same root is used in a verb. The symbols

sH

and

sh

distinguish between a single sound and the

s

- prefix preceding a root that begins with an

h

(in which case it is two distinct sounds).

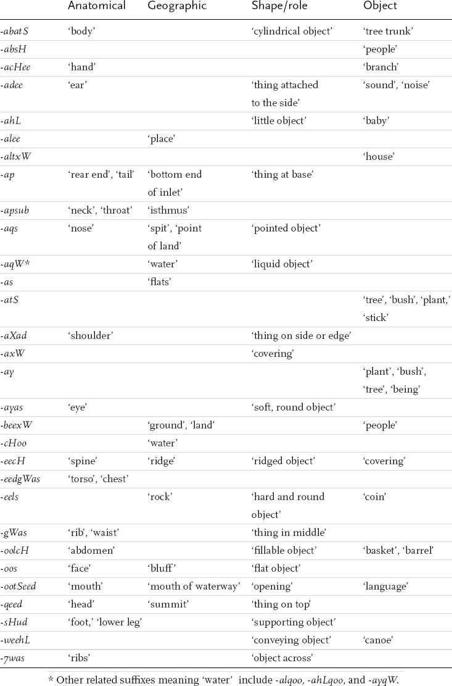

While word roots in the Whulshootseed language usually have distinct meanings, certain suffixes by their very nature are ambiguous. These are called lexical suffixes because they contain meaning rather than refer to a grammatical relationship. They can also influence the meaning of the accompanying root. The following table of lexical suffixes that appear in Seattle place-names shows that a number of these suffixes can differ in meaning depending on whether they are used in an anatomical, geographic, shape/role, or object reference, any of which is possible in place-names. This list is preliminary and is not intended to be exhaustive; it is interesting, for example, that no Seattle place-name is formed with the suffix

-adacH

‘beach’. Some of the lexical suffixes are clearly compounds, formed by combining two of them.

The suffix

-ap

requires some explanation because most English speakers might be inclined to view it as referring to ‘head’ rather than ‘bottom’. In regard to a river, -

ap

refers to the lower end where it drains out. But in terms of an inlet, the suffix refers to the end farthest from the mouth.

There are a number of other reoccurring morphemes (or word parts)

in these place-names. For example, the compound prefix

b-as-

(in entries 40 and 102) means ‘it has’ and indicates that the site contains or is home to the creature or object presented in the remainder of the word. Additionally, the prefix

dxW-

(pronounced similar to the

tw

in ‘twilight’) means ‘place’.

Although both the Waterman and Harrington listings are problematic, with the glosses of some words not matching the transcriptions, the Coast Salishan reference books available today allow further refinement of their combined list.

7

Many times (e.g., 36 and 43) what appear to be remarks of their knowledgeable informants turn out to actually be accurate translations of otherwise-problematic place-names. Thus, some of the riddles of previous versions have fallen by the wayside. One humorous error in Harrington that has been perpetuated until now is the listing of the name for Ballard as

Hát Hat

. Here Harrington and his informant miscommunicated because the Puget Sound Salish language is one of the few in the world that lack nasal consonants in regular speech. The word given,

XátXat

, actually means the duck ‘mallard’ rather than the place-name ‘Ballard’.

8