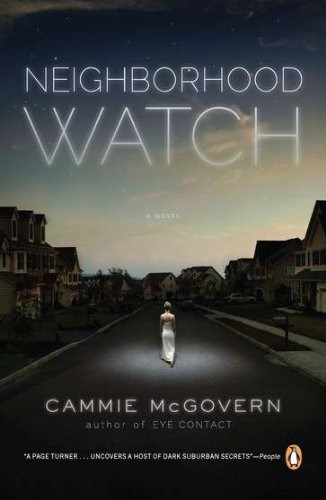

Neighborhood Watch

Table of Contents

Also by Cammie McGovern

The Art of Seeing

Eye Contact

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124,

Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2010 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124,

Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2010 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright © Cammie McGovern, 2010

All rights reserved

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents

either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

McGovern, Cammie.

Neighborhood watch : a novel / Cammie McGovern.

p. cm.

McGovern, Cammie.

Neighborhood watch : a novel / Cammie McGovern.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-101-19020-3

1. Women ex-convicts—Fiction. 2. False imprisonment—Fiction. 3. Self-actualization (Psychology) in women—Fiction. 4. Psychological fiction. I. Title. PS3613.C49N’.6—dc22 2009047210

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For Mikie—whom I love more with every year

V

iolence in the suburbs is not accompanied by the sounds we associate it within cities. No screams or gunfire or sirens. In our case, one ambulance, one fire truck, and five police cars moved onto our street and did their work without a sound. We had only a blanket of silence and the frozen images we gathered, standing at our picture windows watching uniformed men, too many to count, go inside and emerge an hour later with a body, tagged and covered. Though the lips of the ambulance drivers moved as they bore their grim weight into the car, we heard none of the words they spoke. Cocooned in our living rooms, we armed ourselves with telephones and called one another with nothing to say except that we couldn’t believe what we were all seeing.

iolence in the suburbs is not accompanied by the sounds we associate it within cities. No screams or gunfire or sirens. In our case, one ambulance, one fire truck, and five police cars moved onto our street and did their work without a sound. We had only a blanket of silence and the frozen images we gathered, standing at our picture windows watching uniformed men, too many to count, go inside and emerge an hour later with a body, tagged and covered. Though the lips of the ambulance drivers moved as they bore their grim weight into the car, we heard none of the words they spoke. Cocooned in our living rooms, we armed ourselves with telephones and called one another with nothing to say except that we couldn’t believe what we were all seeing.

It’s been twelve years since I lived on Juniper Lane and we watched one another’s lives through windows that opened up like TV screens onto the street. I suspect the houses are no longer identical. Additions have been built. Exteriors painted alternate earth tones. I expect it’s no longer possible to park in the driveway of the wrong house and believe you are home.

When we first moved onto the block, we stood taller than the trees planted on our front lawns. From the highway, our street looked like an oval of Monopoly houses dropped down in a cornfield. We moved here imagining strollers and children’s toys littering the driveway. We pictured sprinklers going, muddy footprints and messes we would one day yell about. We bought these houses assuming the unsettling newness would give way to something else, something more. That was the point, we thought. What we would bring to the identical beige our houses were painted. Life. Mess. Children. But then nothing transpired as anyone planned. For a while it was better than we imagined. And then it was worse.

I was the one who’d insisted on this house. From the first time we saw it, I wanted it more than I could even explain. “Please,” I told Paul, who looked a little pale at the prospect of a mortgage a thousand dollars a month more than we could afford. “We won’t spend money for ten years after this,” I promised, imagining this community would feel like a safety net, a family of some kind, assurance that we wouldn’t be alone.

Then we moved in. The first neighbor I met was Kim, a Korean mother of three. She came over, dictionary in hand, to apologize for what she’d done to our toilet. “It’s a terrible tragedy,” she said, flipping through the pages of her Korean/English dictionary.

“A tragedy?” I said.

“I flush diapers and everything gets backed up. I didn’t know.”

We learned soon enough, when we found a stranger’s tampon floating in our toilet bowl, that the problem—clogged pipes—was endemic and not easy to resolve.

“Isn’t it awful?” asked Barbara, the second neighbor I met. She told me she used a strainer to fish the stuff out before anyone else saw it. “I’m a little tired of hearing my husband point out all our problems.”

It was unsettling, to say the least.

“Yours might be better!” she said, walking away. “Don’t listen to me!”

I try to remember things as clearly as I can, living as I do now in close quarters with women who know nothing of suburbia beyond what they’ve seen on TV. I tell them it wasn’t all perfect. Some days it felt as if we hovered expectantly, our collective breath held for some new piece of bad news. I tell them nothing was exactly how it looked. Some days it seemed as if the drama we’d moved there hoping to avoid was, in some way we couldn’t explain, what we were all waiting for.

One thing that’s easier about living in prison: The worst has already happened.

CHAPTER 1

I

n the twelve years I’ve lived in the Connecticut Correctional Institute for Women, I’ve tried in vain to forget about the past and focus instead on the here and now, on contributions I can make to improve the quality of life for everyone in here. I am different than most of the other inmates, who’ve grown up in either juvenile detention centers or trailer parks they shared with rats that were, for some, more pleasant than their stepfathers. Scratch a female inmate, I’ve discovered, and you’ll usually find a girl whose mother had terrible taste in men. I’ve also learned this much: I’m not better than any of these women, nor—for all my education and degrees—am I smarter. We’ve made the same mistakes, misjudged other people and ourselves.

n the twelve years I’ve lived in the Connecticut Correctional Institute for Women, I’ve tried in vain to forget about the past and focus instead on the here and now, on contributions I can make to improve the quality of life for everyone in here. I am different than most of the other inmates, who’ve grown up in either juvenile detention centers or trailer parks they shared with rats that were, for some, more pleasant than their stepfathers. Scratch a female inmate, I’ve discovered, and you’ll usually find a girl whose mother had terrible taste in men. I’ve also learned this much: I’m not better than any of these women, nor—for all my education and degrees—am I smarter. We’ve made the same mistakes, misjudged other people and ourselves.

Officially I am the prison librarian, a job for which I get paid thirty-five cents an hour. I solicit donations from publishers and local libraries, and in twelve years have transformed a bookshelf of thirty tattered paperbacks into a library of more than six hundred titles, some delivered straight from the publisher. Books with pages so sharp and clean the girls have gotten paper cuts turning them.

For the last six years I’ve also served as an inmate representative on the prison welfare committee. There I won Wanda her right to keep more than one nail polish in her cell so she could re-create her old days as New Haven’s most popular manicurist, the life she had before she shot and killed the husband who’d been beating her for fourteen years. Wanda is my best friend here, and I believe her when she says she felt like she had no other choice.

What’s done is done,

she says,

and I’d like to get back to work

.

What’s done is done,

she says,

and I’d like to get back to work

.

To a certain extent, she can. Not for money, of course, but she can ply her trade, as can I. Once upon a time I was at the top of my class in the UConn Library Science Program. I was the first hired and the fastest-rising assistant to the head librarian the Milford Town Library had ever seen. Readership, circulation, and interlibrary loans all increased under my stewardship right up until the day I was arrested, after which, of course, I have no more figures. We were on the cusp of numbers that would win us more state funding. I wouldn’t mind knowing what became of that, but I don’t.

The media dubbed me “the Librarian Murderess.” One newspaper described me as a “Victorian Volcano,” as if being a librarian might still be a reflection of one’s sexual mores, which of course is ridiculous and archaic thinking. We librarians like books. We also enjoy research. Above all, we like serving people, which is what defines librarians, not our myopia or our sexless hair buns. We believe that when books are present and learning is possible, all people benefit. In my time here I’ve watched a twenty-three-year-old woman learn to read to keep up with her daughter in the first grade on the outside. I’ve watched another go from reading only the worst of our most popular titles—the blood-soaked crime novels the women here have a bottomless appetite for—to other genres: a collection of short stories, a biography of a tennis pro. Small satisfactions, but real ones nevertheless. Sometimes I believe I’ve made a larger difference here than I could have at my old job, where—let’s be honest—the illiterate didn’t often walk through the door.

But a recent flurry of attention surrounding my life here has been a little unnerving. Some years ago, following a

Phil Donohue Show

featuring inmates freed after new DNA testing proved them innocent, I had twenty women stop by my library looking for stationery and ballpoint pens. I’ll admit that I got caught up by the episode, too. The shaggy-haired blond man looked in the camera, one prominent front tooth missing, and said, “Freedom is the sweetest drink I’ve ever tasted.” He’d served twenty-six years in prison for a rape he didn’t commit against a woman he’d never met. For the women who came in, I started an impromptu seminar on formal letter writing: “Don’t end every sentence with an exclamation point!” I told them. “Don’t dot your

i’

s with little hearts!” For me, the pleasure was watching women who’d written nothing for years pick up a pen and compose sentences on paper.

Yes,

I thought, my heart filled with the warmth of purpose,

here it is, the reason I’m here.

None of us knew there would be a two- to three-year wait for new DNA testing. That it would require petitions, judges’ orders, and exorbitant costs. Or that the tests were often too inconclusive to warrant a new trial or verdict reversal. I learned this only over time, doing my own research. I tried to tell my writing group not to get their hopes up. “There’s a backlog of requests since that show,” I said. “Hundreds, probably.” More like thousands, but I didn’t want anyone to get too discouraged.

Phil Donohue Show

featuring inmates freed after new DNA testing proved them innocent, I had twenty women stop by my library looking for stationery and ballpoint pens. I’ll admit that I got caught up by the episode, too. The shaggy-haired blond man looked in the camera, one prominent front tooth missing, and said, “Freedom is the sweetest drink I’ve ever tasted.” He’d served twenty-six years in prison for a rape he didn’t commit against a woman he’d never met. For the women who came in, I started an impromptu seminar on formal letter writing: “Don’t end every sentence with an exclamation point!” I told them. “Don’t dot your

i’

s with little hearts!” For me, the pleasure was watching women who’d written nothing for years pick up a pen and compose sentences on paper.

Yes,

I thought, my heart filled with the warmth of purpose,

here it is, the reason I’m here.

None of us knew there would be a two- to three-year wait for new DNA testing. That it would require petitions, judges’ orders, and exorbitant costs. Or that the tests were often too inconclusive to warrant a new trial or verdict reversal. I learned this only over time, doing my own research. I tried to tell my writing group not to get their hopes up. “There’s a backlog of requests since that show,” I said. “Hundreds, probably.” More like thousands, but I didn’t want anyone to get too discouraged.

After a few months, the group whittled down to a handful of the most single-minded women, who, unfortunately, also seemed the most guilty. Rayanne, in for stabbing her landlord, a crime witnessed by eight other people, has continued writing letters steadily for four years, pleading for her case to be reopened. She was being threatened at the time of her crime, she argues. She was high on drugs. The place was dark. She heard a gun. What she means is,

Yes, I did it. But it wasn’t my fault

.

Yes, I did it. But it wasn’t my fault

.

I wrote letters, too. As an example for the others, and thinking of the blond man imprisoned for twenty-six years. I loved his story, the footage they showed of his handwritten note. For a year, I received nothing beyond the standard form letter, cautioning patience and explaining the inundation of requests. Then, about three years ago, I got a letter which I thought at first was from a lawyer. Inside the envelope, typed on a plain white sheet of paper, was a single sentence:

Think about the cat.

Think about the cat.

Other books

Sweet Alibi by Adriane Leigh

The Third-Class Genie by Robert Leeson

The Trade by Barry Hutchison

Poseur #3: Petty in Pink: A Trend Set Novel by Rachel Maude

The Mystical Knights: The Sword of Dreams by K.A. Robertson

Harmonized by Mary Behre

Bastard out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison

Smashed in the USSR: Fear, Loathing and Vodka on the Steppes by Walton, Caroline, Petrov, Ivan

Life in a Rut, Love not Included (Love Not Included series Book 1) by J.D. Hollyfield