Nelson: Britannia's God of War (24 page)

Read Nelson: Britannia's God of War Online

Authors: Andrew Lambert

Nelson had anticipated a battle at anchor, adding a signal for cables and springs to be run out through the stern ports to his repertoire of flags at the outset of the cruise. He flew the necessary signal at 4.22, as the ships entered the bay. Unlike Brueys’ force, which had more time to act and no sails to handle, the British ships were prepared by the time they joined the fight, although the failure of three ships to control their stern cables suggests the margin was close. The job was made that much easier by the process of beating to quarters, with marine drummers signalling the ship to ‘clear for action’ as the men removed partitions, bulkheads, spare gear, livestock, and even dinner, to ensure nothing interfered with the smooth steady operation of the guns. Elsewhere the surgeon and his team prepared the cockpit for service as a makeshift operating theatre, and warmed their instruments on Nelson’s specific instruction – for him, the sensation of steel cutting into living flesh was all too recent a memory.

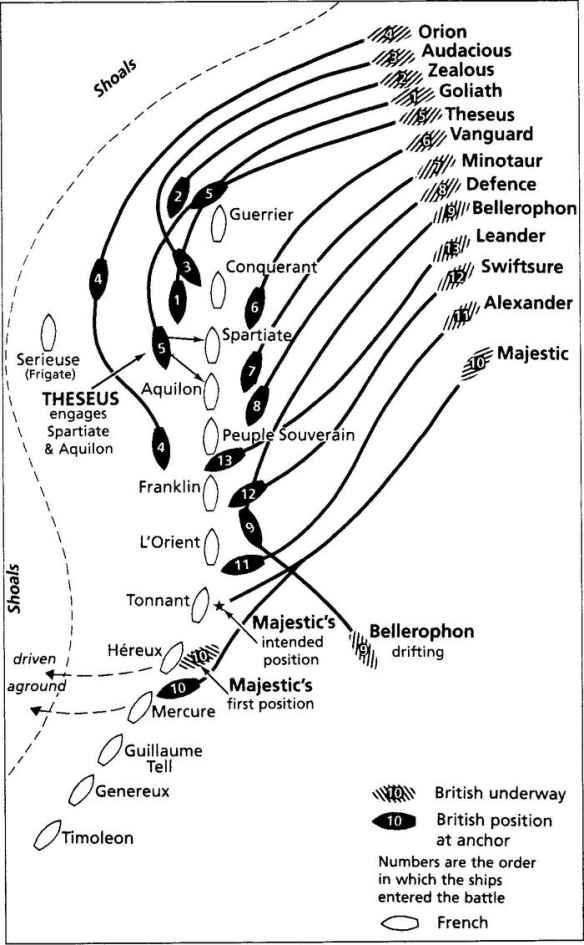

At 4.52 Nelson signalled for an attack on the van and centre, a concentration of force against part of the enemy line, which he selected because the wind was blowing directly down the French line, making it almost impossible for the rear ships to take part in the opening stages of the battle. He did not know that Brueys had put his weakest ships in the van. He also signalled for each ship to place four lanterns in a vertical alignment on the mizzen mast, to avoid friendly fire after dark.

Having won the race to lead the line, Foley was responsible for the opening move, and like his chief he did not flinch from exploiting the opportunities his practised eye discerned, satisfied his well-drilled crew would meet his expectations. As he closed the French line Foley could see that the ships were at single anchor, and he worked out that he could sail round the leading French ship, attacking on the inshore side where he expected they had not prepared for battle. At almost the same moment Nelson saw the opening, although it was too late for him to signal. This strongly suggests that Nelson, having foreseen a battle at anchor, let his captains know that he favoured doubling on the enemy line following the precedent set by Lord Hood off GourjeanBay back in 1794. The only question left for Foley to settle was whether he could get inside the French ships.

The battle of the Nile

As

Goliath

rounded the head of the French line Foley fired a first broadside into the bows of the feeble old

Guerrière

, causing serious damage and loss of life. He planned to anchor alongside, where he was delighted to see the French gunports still packed with stores and quite unprepared, but the anchor cable through the stern ports was allowed to run out to the full extent, and she brought up between the second and third ships in the French line. This left a space for Hood, who also poured his first broadside into the bows of the

Guerrière

before taking up a position off her port bow, which gave the

Zealous

a favourable angle of attack. Gould in the

Audacious

followed him round, fired into the

Guerrière

and then anchored between her and the next ship, the

Conquerant

.

Saumarez swept further inshore to clear his squadron mates, planning to attack the third French ship, the

Spartiate

:

however, the frigate

Sérieuse

rashly fired on the

Orion

. Saumarez waited for his puny opponent to close, before pouring in a single broadside that dismasted and sank the French vessel. In the process

Orion

missed her mark, and brought up on the bows of the fifth French ship,

Peuple

Souverain

. Miller took the

Theseus

round the head of the line, her fire dismasting the unfortunate

Guerrière

, before picking his way between the

Zealous

and her target, to avoid the inshore shoals. He took position off the bow of the

Spartiate

.

Nelson had watched his captains open the battle in magnificent style; now he elected to change the angle of attack. The inshore berth, as Miller had found, was becoming crowded. It was time to double on the enemy, and he turned outside the line, placing

Vanguard

alongside the

Spartiate

. The next two ships astern,

Minotaur

and

Defence

, followed him, extending down the French line to engage

Aquilon

and

Peuple

Souverain.

Bellerophon

failed to bring up alongside the eighty-gun

Franklin

, a formidable opponent for a medium-sized seventy-four, ending up off the bow of the three-decker

L

’

Orient

, a ship with a tremendous advantage in weight of broadside and height out of the water.

Majestic

,

the last of the ships in close order when the attack began, arrived off the French line little more than thirty minutes after

Goliath

had rounded the

Guerrière

. She also missed her mark. It was now dark, and gunsmoke was beginning to shroud the battlefield.

Majestic

ended up bow-on to the

Hereux

, the ninth ship in the French

line, unable to fight her guns and under heavy musket fire from the French ship. Captain Westcott was killed before anything could be done. That these two ships both made serious errors of positioning reflected their inability to see the target. Both would pay heavily for their admiral’s temerity in launching an attack under such difficult conditions.

Further out, Troubridge had cast off his prize at 3 o’clock and hastened to join the fight. He never arrived. As he rounded Aboukir Island he cut the corner and failed to clear the shoal, going hard aground at 6.40. Never one to dwell on a disaster, Troubridge immediately signalled that the

Culloden

was aground, to warn

Alexander

and

Swiftsure

,

then coming up astern, and called Hardy over in the tiny

Mutine

to lay out his anchors in an attempt to get the ship off. Despite lightening ship, and using every exertion, the

Culloden

was stuck fast, pinned at the bow and stern, her fire-eating captain condemned to be a spectator at the greatest naval battle ever fought. Coming up astern Ball and Hallowell arrived at the French line around 8 o’clock. They entered a diabolical scene, the dark night and thick smoke repeatedly punctured by sharp, stabbing flames from guns, whose thunderous noise was counterpointed by high-pitched yells and screams. That excellent seaman Ball calmly took the

Alexander

into an ideal position, just off the after-quarter of the French flagship, where his broadside would tell on her weak stern galleries, without risking the response that had already dismasted and shattered

Bellerophon

. She had cut her cable and was drifting down wind, out of the action and without her recognition lights. She was nearly fired on by

Swiftsure

, but fortunately for all concerned Hallowell had decided to take up his position before opening fire. This meant that he could furl and secure his sails before releasing the men to serve the guns, thus avoiding the problems suffered by three of his predecessors.

Leander

was the only fighting ship not engaged, or aground. Thompson’s first thoughts were to assist

Culloden

,

but Troubridge advised him to join the battle. Thompson finally got into the fight after 9 o’clock, taking up a perfect position across the bow of

Franklin

.

Twelve of Nelson’s thirteen fighting ships had now been in action: one had already been knocked out, and another heavily hit, but the attack had been a remarkable success. The van of Brueys’ fleet was being overwhelmed, while his rear was unengaged. With the ships at or inside point-blank range the battle now settled into a steady

exchange of fire. The limited damage that any one shot, or even broadside, could inflict made naval battles in this era a question of hours, not minutes. The faster and more accurate broadsides of the British soon dominated the contest, gradually breaking the physical and mental resistance of the enemy. The French fought bravely, but they fought like men resigned to defeat, their officers more anxious to show how well they could die than to win the battle. Nelson and his captains were also setting an example of bravery under fire, to inspire their men, but they were looking for opportunities to secure victory. The gun crews toiled away in an environment of stunning noise and parching smoke, knowing that any error in drill could be disastrous. They had no concept of the battle, only of their immediate surroundings, punctuated by occasional reports from the topsides. In the magazines powder charges were packed and handed on to boys too small to haul the gun tackles, while ready-use shot were stored on the deck, with the main supply in the shot lockers down in the hold, which had to be opened once the initial supply had been fired.

Casualties were an inevitable part of such battles: they were quickly removed, usually by their messmates. The dead were unceremoniously heaved overboard, to maintain morale and keep the sanded decks free of slippery gore. The living were taken down to the cockpit, to wait their turn with the surgeon. At 8.30 Nelson joined them. Standing with Berry, looking at a sketch of the bay taken from a French prize, he was hit on the forehead by a scrap of iron from an anti-personnel projectile. It was a nasty wound: the flesh was cut away from the skull over an area an inch long and three inches wide. The blow knocked him off-balance, but Berry caught him.

It was at this moment that Nelson demonstrated his underlying Wolfe fixation. He was about to win the greatest naval battle of all time so, in the manner of his hero, it was the perfect time to die. The enemy had now obliged. He could go to meet his maker, and the architect of his destiny as one of the immortals. Stunned and blinded, his only good eye covered by detached flesh and copious amounts of blood, he began to ‘perform’ the Death of the Hero. There had to be an affecting death scene, something for Benjamin West to capture in oils, for posterity to record, for his countrymen to admire and lament. This time he did not quite rise to the occasion: all he could offer was ‘I am killed; remember me to my wife’, before Berry applied a dressing and had him helped below. Staggering down three companion ways

Nelson began to recover his composure. By the time he reached the cockpit he insisted on waiting his turn – there were far worse injuries to be dealt with. Surgeon Jefferson quickly cleaned up the wound, bringing the edges together with sticking plaster and a bandage. He sent the stunned admiral to the nearby bread room to rest, and to get out of his way. Determined to have his say Nelson called for his Secretary, who had been slightly wounded, and tried to dictate an official report. The Secretary, overcome by the situation, passed the task to the chaplain, but they soon gave up. There was not enough light and even Nelson needed to rest, if only to allow the first symptoms of shock to pass.

His battle was going well.

Majestic

escaped from her dangerous position when her jib-boom gave way, and brought up between

Hereux

and

Mercure

, able to fire on both with relative impunity. At the head of the line

Guerrière,

Conquerant

and

Spartiate

were overwhelmed, surrendering after two to three hours of unequal combat, in which they lost hundreds of men.

Aquilon

was

also doubled and lasted no longer, while

Peuple

Souverain

put up a stout fight, hitting Saumarez and his ship quite hard, until her cables were cut and she drifted out of the line. The vacant position exposed

Franklin’s

bow, and Thompson exploited it to perfection. With her decks being repeatedly raked the big eighty-gun ship was soon reduced to a helpless wreck, but her surrender was delayed by more startling events.

L

’

Orient

, Brueys’ flagship, was a tougher nut. Her height out of the water, weight of fire and heavily built hull made her a difficult opponent. After dismantling

Bellerophon

, which suffered a quarter of the British casualties, she was attacked with more skill by Ball and Hallowell.

Alexander

fired into her stern, killing Brueys, and starting a fire in the great cabin. The fire quickly spread: some accounts suggest that oil-based paint had been left on deck, while Hallowell deliberately directed his guns into the blazing mizzen chains to stop any fire-fighting. An explosion was inevitable; Ball cut his cable and moved down the line, Saumarez ordered fire precautions, while Hallowell, confident that any explosion would be vented upward by the stout hull, wetted his sails and decks and sat tight close to the blazing three-decker. Astern of the flagship

Tonnant,

Hereux

and

Mercure

cut their cables: the former was dismasted, the others went aground.