Niagara: A History of the Falls (7 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

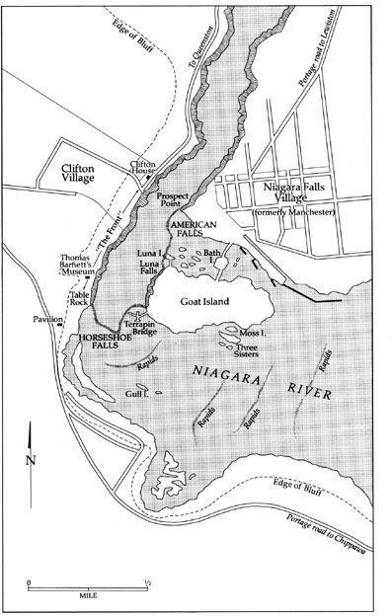

In spite of the vast chunk that had toppled off Table Rock in 1818, this intimidating ledge of dolostone still projected fifty feet over the Falls – so close to the crest that one traveller felt he could almost dip his toe into the raging water (the distance was a little less than five feet). The bolder visitors crept to the very lip of the overhang and some, such as Frances Trollope, the writer and mother of the novelist Anthony Trollope, were moved to tears as Thomas Moore had been.

A guide to the Fashionable Tour, as it was called, warned those who attempted to climb down Forsyth’s spiral staircase from Table Rock to be wary about going farther. “The entrance to the tremendous cavern beneath the falling sheet should never be attempted by persons of weak nerves,” it warned. In spite of her tears, Mrs. Trollope’s nerves were not weak. Others might shrink back; indeed, she “often saw their noble daring fail” (a hint of condescension here) as “dripping and draggled” they fled back up the stairs, “leaving us in full possession of the awful scene we so dearly gazed upon.”

She clearly relished the experience, which she described in an acerbic and controversial book,

The Domestic Manners of the Americans

. “Why,” she asked, “is it so exquisite a pleasure to stand for hours drenched in spray, stunned by the ceaseless roar, trembling from the concussion that shakes the very rock you cling to, and breathing painfully the moist atmosphere that seems to have less of air than water in it? Yet pleasure it is, and I almost think the greatest I ever enjoyed.”

The Falls,

circa

1825

Even she, however, could not hazard the full experience. “We more than once approached the entrance to this appalling cavern, but I never fairly entered it … I lost my breath entirely; and the pain at my breast was so severe, that not all my curiosity could enable me to endure it.”

Flushed with success and encouraged by the canal open for business, Forsyth in 1826 added two wings to the Pavilion and plunged into a series of acrimonious disputes that were to be his downfall. He was a rogue, certainly, but in the struggle for the tourist dollar that was just beginning, all were rogues of a sort. The successful rogues had the political establishment on their side; Forsyth didn’t. For all of a decade he battered his head against the unyielding wall of officialdom. One cannot help admiring his stubbornness, if not his greed.

For greed brought him down. He didn’t want a piece of the Falls; he wanted it all. This single-mindedness antagonized his rivals. These included John Brown, who had opened the Ontario House a short distance upriver, and two miller-merchants, Thomas Clark and Samuel Street, Jr., who had beaten Forsyth and secured ferry rights on the river in 1825.

All were interconnected. Clark also owned a chunk of Brown’s hotel. A powerful figure in the burgeoning community and a former member of the Legislative Council, he had the ear of the lieutenant-governor. He and his partner, Street, were among other things land speculators and money-lenders; the fact that many of the most prominent figures in the region were in his debt gave him an edge that Forsyth could not command.

Forsyth was stubborn to the point of being bullheaded. When Brown built a plank road from his hotel to the Falls, Forsyth ripped it up. When Clark and Street got ferry rights on the river, Forsyth mounted a pirate operation, harassing the partners so aggressively that they couldn’t operate.

Charges, countercharges, and lawsuits enlivened the battle. When Brown’s hotel burned down mysteriously, Clark spread the rumour that Forsyth was to blame. When Brown rebuilt it, he found that Forsyth had encircled the Pavilion with a high board fence, shutting off all access to Table Rock and the Falls. But the government had set aside a public strip one chain (sixty-six feet) wide along the river bank as a military reserve. This was Crown property, and Clark persuaded the lieutenant-governor to send a troop of engineers to tear the illegally placed fence down. When Forsyth put it back up, the army tore it down again, an act that many considered an outrageous use of the military over an issue that should properly have been decided in the courts. Forsyth sued; but when the civil suit was finally argued, he lost. He lost again when Brown sued him for tearing up his road. He lost a third time when Clark and Street sued him for ruining their ferry business. That should have been enough, but Forsyth refused to give up. He filed two countersuits and lost those, too.

These civil actions failed to stop the irrepressible hotelier from operating his illegal ferry system. What Clark needed was a criminal action. To effect that, he managed to wangle a licence of occupation – something Forsyth had failed to get – for that part of the old military reserve that lay near his dock. The government reasoned that this would “keep the shore open and free of access to the public who had been shut out by Forsyth.” Now the Pavilion’s owner realized he could go to jail if he trespassed on what had become the licensed property of his rivals.

In the end Forsyth was beaten down. His attempts to corral the tourist trade at the Falls had failed. In 1833 he sold out – to Clark and Street. The winners immediately focused their attention on an ambitious real-estate speculation, which they named the City of the Falls. In spite of the grandiloquent title, it was an ordinary subdivision of fifty-foot lots to be laid out on Forsyth’s old property. Its purpose, they claimed, was to preserve the area from vandalism and commercial enterprise!

Future residents of the City of the Falls were to have the use of a fashionable Bath House complete with Pump Room and Dance Hall. But this attempt to create a miniature Saratoga Springs at Niagara failed. Only a few lots were sold, in spite of an aggressive advertising campaign, while the attempt to pump water up from Table Rock to a reservoir in a tower collapsed when the wooden pipes burst. As a result there was water, water everywhere except in the Bath House, which fell into disuse and subsequently burned. The entire scheme folded, and the investors, including Clark and Street, lost heavily. As for the Pavilion, it was soon superseded by the more luxurious Clifton House, named for the struggling community growing up on the Canadian bank of the gorge.

It was here that the Front was born – that notorious quarter-mile strip, just three hundred yards wide, that ran from Table Rock to the Clifton House and provided a haven for half a century for every kind of huckster, gambler, barker, confidence man, and swindler. Here half a dozen hotels soon sprang up along with a hodge-podge of other shops, booths, and taverns. And here Thomas Barnett built his famous museum with its Egyptian mummies and Iroquois arrowheads.

The City of the Falls had failed, but the Front was its byproduct. Those canny promoters, Clark and Street, had used their influence to occupy most of the military reserve, something Forsyth had never been able to achieve. What they could not occupy legally they grabbed anyway. When the new governor sent the army down to stop them from erecting buildings on the reserve, they sued for damages, even though the soldiers had been careful to remove only one stone. The courts, however, awarded the partners five hundred pounds and then gave them a deed to the whole. It would take another protracted court action and many years of protest before the Front finally wound down.

3

The jumper and the hermit

The long carnival began on September 8, 1827. The natural spectacle was no longer enough – or so the entrepreneurs believed. If the crowds required further titillation, they would provide it. And the cataract provided a perfect backdrop.

William Forsyth began it before he sold out, with the help of John Brown, of all people. The lure of mutual profit wiped out, at least temporarily, their personal vendetta. Forsyth could not let the Falls go to waste; to him, the thundering cataract, rattling the windows of the Pavilion, ought to be

used

. He was the first of a long line of promoters who felt the same way.

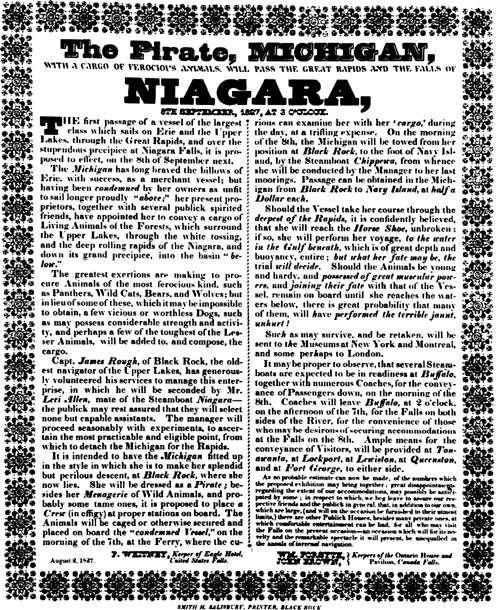

He and Brown roped in an American, Parkhurst Whitney, proprietor of the Eagle Tavern on the other side, and together the trio devised a spectacular feat. If the Falls inspired horror, then Forsyth intended to pour on more horror – albeit slightly counterfeit. He could scarcely send a human being over the Falls (that would not occur to anyone until the start of the next century), but he could send some four-footed surrogates. He and his partners would buy a condemned vessel, deck it out as a pirate ship, and, with a cargo of “wild and ferocious animals,” send it hurtling over “the stupendous precipice” of the Horseshoe Falls. The posters heralding the event anticipated the extravagant style that Phineas Barnum was about to make famous: “The greatest exertions are making

[sic]

to procure Animals of the ferocious kind, such as Panthers, Wild Cats, Bears and Wolves; but in lieu of some of these, which it may be impossible to obtain, a few vicious or worthless Dogs, such as may possess considerable strength and activity, and perhaps a few of the toughest of the Lesser Animals, will be added to, and compose, the cargo.…

“Should the Animals be young and hardy, and

possessed of great muscular powers

, and

joining their fate

with that of the Vessel, remain on board till she reaches the waters below, there is great probability that many of them, will have

performed the terrible jaunt, unhurt!”

The idea of actual living beings plunging headlong into the unforgiving waters was tempting to those who, no doubt, would have welcomed the return of bear-baiting. Certainly the crowds that blackened the treetops, housetops, hotel verandahs, and wagons to witness “the remarkable spectacle unequalled in the annals of

infernal

navigation” were the biggest yet seen at Niagara. Estimates ranging from ten thousand to thirty thousand were bandied about. Stages and canal boats had been crowded with visitors descending on the twin communities. Wagons poured in, crammed with farmers and their families. Five steamboats loaded with thrill seekers arrived from Lake Erie, each with a brass band on deck. Gamblers brought wheels of fortune; hucksters set up stalls to hawk gingerbread and beer. Upper-class ladies arrayed themselves in what the

Colonial Advocate

called “the pink of fashion.” Hotels and taverns were overbooked.

At three that afternoon, with the Stars and Stripes at its bow and the Union Jack at its stern, the derelict merchant ship

Michigan

was towed to a point just above the rapids. There was no crew, but effigies of sailors lined the decks. The cargo scarcely lived up to its billing: two bears, a buffalo, two foxes, a raccoon, an eagle, a dog, and fifteen geese.

With an approving shout from the crowd, the

Michigan

entered the first set of rapids. The rest was anticlimax. The ship lost its masts and began to break up before reaching the crest of the Falls. The bears and the buffalo jumped overboard; at least one bear was recaptured and put on display. The ship broke in half, tumbled over the precipice, and went to pieces. One of the geese survived. None of the other animals was found.

The results exceeded the promoters’ wildest dreams. So much liquor and beer were consumed in the taverns and hotels that the entire stock was drunk up before half the crowd was accommodated. The message was clear: the Falls was not simply a static spectacle to be gazed upon and admired; now it could be

used

.

Two years later the first of the Niagara daredevils turned up in the person of Sam Patch, the Jersey Jumper, a twenty-three-year-old millhand who had perfected his curious vocation by leaping into millponds. Patch had been astonishing crowds by his high jumps into raging waters, including a seventy-foot leap into the chasm at Passaic Falls in New Jersey and a ninety-foot plunge from the masthead of a Hoboken sloop. In October 1829, he was invited to the Falls by a group of Buffalo businessmen who had talked of drawing crowds by blowing up a dangerous corner of Table Rock and now saw a chance to mount a stronger attraction.