Nicholas and Alexandra (49 page)

Read Nicholas and Alexandra Online

Authors: Robert K. Massie

Livadia: Pierre Gilliard with Olga and Tatiana

At Spala: Alexandra

After Spala: Alexis. The Tsarevich's left leg is bent and a metal brace is attached to his shoe

In a hospital:

(from left)

Olga

(partly hidden),

Tatiana

(foreground),

Alexandra Nicholas and Alexis inspecting a Cossack regiment during the war

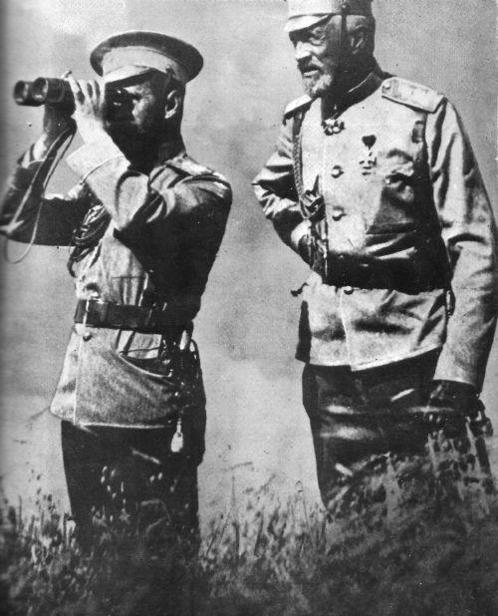

The Tsar with Grand Duke Nicholas

facing:

Anastasia

Marie, Tatiana, and Olga

(seated)

Nicholas, Alexis, and Tatiana, 1916

The Empress

Imprisoned at Tsarskoe Selo, 1917

Hasn't the Emperor too many Germans among his subjects already? Galicia? It's full of Jews! . . . Constantinople, the Cross on Santa Sophia, the Bosporous, the Dardanelles. It's too mad a notion to be worth a moment's consideration. And even if we assume a complete victory, the Hohenzollerns and Hapsburgs reduced to begging for peace and submitting to our terms—it means not only the end of German domination, but the proclamation of republics throughout central Europe. That means the simultaneous end of Tsarism. I prefer to remain silent as to what we may expect on the hypothesis of our defeat. . . . My practical conclusion is that we must liquidate this stupid adventure as soon as possible."

Paléologue, whose job it was to do everything possible to keep Russia in the war fighting on France's side, watched Witte go and mused on the old stateman's character: "an enigmatic, unnerving individual, a great intellect, despotic, disdainful, conscious of his powers, a prey to ambition, jealousy, and pride." Witte's views, he reflected, were "evil" and "dangerous" to France as well as to Russia.

Nowhere was Nicholas's optimism more keenly shared than among the officers of the Russian army. Those unlucky enough to be stationed with regiments far from the frontier were frantic with worry lest it all be over before they had a chance to see action. Guards officers, fortunate enough to be leaving immediately for the front, asked whether they should pack their dress uniforms for the ceremonial parade down the Unter den Linden. They were advised to go ahead and let their braid and plumes follow by the next courier.

Day after day, the capital trembled to the cadence of marching men. From dawn until nightfall, infantry regiments marched down the Nevsky Prospect, bound for the Warsaw Station and the front. Outside the city, other regiments of infantry, cavalry squadrons and batteries of horse artillery clogged the roads leading toward the Baltic provinces and East Prussia. In motion with only casual organization, the soldiers walked rather than marched, followed in no particular order by long columns of baggage carts, ammunition wagons, ambulances, field kitchens and remount horses. So dense were the moving columns that in places they left the roads and spread out across the dry summer fields, swarming in a jumbled confusion of dust, shouts, horses' hoofs and rumbling wheels, recalling the Tartar hordes of the thirteenth century.

Paléologue, driving back to the capital from an audience with the Tsar, encountered one of these regiments marching along a road. The