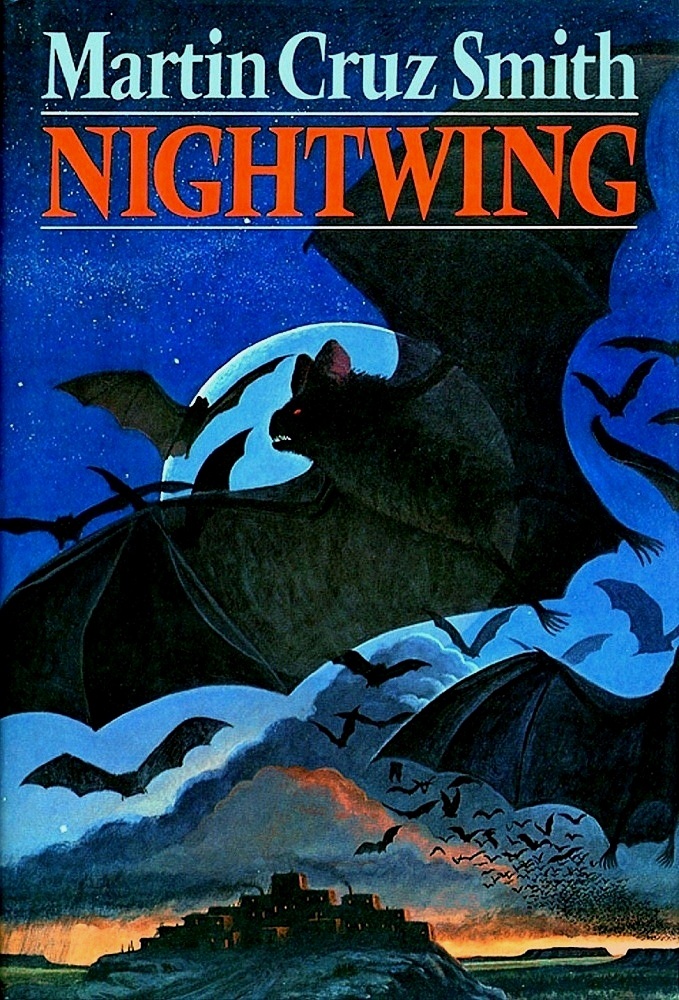

Nightwing

Authors: Martin Cruz Smith

N I G H T W I N G

The old Indian sits in the heat of his shack in the Painted Desert. The Hopis, his people, are dying a slow death, the death of the desert. Navajos are taking their land, the Indian Bureau is selling Hopi water, and the energy companies are ripping apart the sacred mesa.

Against such power what can one old medicine man do? The colored sands hiss through his hand into an intricate painting. Black for death, red for blood. “I’m going to end the world,” the old man tells Youngman Duran, a bemused and cynical ex-convict the Hopis have made into a deputy, but not quite into a lawman.

“When?” Youngman smiles.

“Today.”

Next morning the old medicine man is dead, bled to death where he lies in the center of his painting. That is the start of his prophecy come true. Every night from then on Death stirs. Its call is a whisper, its wings are wide and gossamer thin, its teeth are sharp as knives, its grotesque appetite insatiable. As carrier for the most virulent of all diseases, this Death becomes a tide that threatens to sweep man from the American Southwest.

The burden of destroying the death falls on Youngman, who alone has understood the words of the painting, and on the obsessed scientist Hayden Paine, whose life is the pursuit of death.

Together, in this chilling novel of suspense, they journey to the one place of the Hopi, both holy and infected, where, as the wise man had told, the choice must be made—to live or to die—and be made quickly. For night is falling.

This work is a novel and the characters and incidents depicted in it are entirely fictional.

Copyright

©

1977 by Martin Cruz Smith. All rights reserved. Published simultaneously in Canada by George J. McLeod Limited, Toronto. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Smith, Martin, 1942–

Nightwing: a novel.

1. Title.

ISBN: 0-393-08783-2 Book design by Antonina Krass

Book design by Antonina Krass

Jacket Design and painting

©

1977 by Wendell Minor

W • W • NORTON & COMPANY • INC • NEW YORK

F

OR

K

NOX AND

K

ITTY

When was I born?

Where did I come from?

Where am I going?

What am I?

—the Hopi questions

N I G H T W I N G

C H A P T E R

O N E

T

he Red Man tobacco sign—an Indian profile with a corroded eye—stared west. Two pickup trucks rusted in a bower of yellow creosote bushes. Out of a headlight socket flicked the quick ribbon of a lizard tongue.

It was noon in the Painted Desert. A hundred degrees.

The tobacco sign and car hoods welded together in upright rows were the walls of Abner Tasupi’s shed. A square of sheet steel was the roof. Sometimes, Abner fixed cars and, sometimes, he sold Enco gasoline straight from a drum. Usually, the drums were empty and he spent the day listening to his transistor radio. They had Navajo disc jockeys on a Gallup station. While he hated Navajos, there were no Hopi disc jockeys. There were lots of Hopis up on the Black Mesa, but not a one that dared come visit him.

Well, one.

Youngman Duran sat in the shed between the erupting springs of a car seat. A half-empty jug of Gallo port nestled between his legs.

“I’m sorry,” Abner apologized to his only friend, “but they got to die.”

“Anyone I know?”

Stripped down to underpants and a leather kilt, Abner squatted in the center of the dirt floor grinding cornmeal. He was past ninety and his brown body was hard like an insect’s. His gray hair, cut short above the eyes, hung down to frame a flat face with broad cheekbones and wide, peeling lips.

“Come on, Abner, you can tell me. Hell, I’m not a deputy for nothing.”

Youngman was a third of Abner’s age. His hair was shorter, pitch-black and tucked under a dirty Stetson. Sweat ringed the crown of his hat and sweat stains from his armpits and back merged to turn most of his khaki shirt into a dark sponge. He shifted his seat, trying to get comfortable without sticking himself with a seat spring. Youngman hated port wine but real alcohol was hard to find on the reservation. Besides, he liked Abner.

Abner gathered ground cornmeal in his hands and started pouring it inside of the door and, moving backwards, around the corners of the room.

“Everyone you know.”

Youngman pulled out a pack of damp cigarettes.

“Well, that’s a start, Abner, that’s a start.”

The shed always struck Youngman as a flood mark where the junk of different civilizations was left high and dry. A box of spark plugs and points. Tire irons and jacks. Soup and bean cans on a drum converted into a stove. T-shirts stuffed into holes in the wall, where ears of blue corn hung from braided husks. On an orange crate shelf stood a line of kachina dolls, each a foot tall, one crowned with wooden rays of the sun, another wearing eagle fluffs, the crudely carved kind fifty to a hundred years old or more.

“You know, you get $1,000 for one of those dolls in Phoenix. Might as well do it before someone comes and steals ’em.”

“No one comes around here, Flea.” Abner finished pouring corn. “I don’t worry about that.”

“Well, they figure you’re going to hex ’em, Abner.”

On a steamer trunk were mason jars of peyote and datura, ground jimson weed. Youngman resisted the temptation to dig in. He’d been strung out before; he’d spent seven years trying to stay strung out. But that was the Army. Now he only smoked a little grass and drank wine. The highs weren’t so high, but he didn’t come so close to touching bottom. Abner was different. Abner was a priest. And Abner was right, people stayed away from him.

“Just what the hell do you mean, everyone’s going to die? You’re lucky you’re talking to me. Anyone else would take you serious, Abner. You know that.”

The lid was off the datura jar. The steamer trunk was bandaged with travel stickers reading “Tijuana,” “Truth or Consequences,” “Tombstone.” There could as well have been one that said “Mars.” Abner had picked up the trunk in a pawn shop, he’d never been farther than Tuba City.

“It’s a hot day and the Gallo brothers worked real hard, Abner. Have some.”

Abner shook his head. Old man’s been in the datura, Youngman thought. A fat dose of ground seeds was poison. A small dose of dried roots lifted the brain like a car on a jack. There were a lot of ways to die on a reservation. Drink. Datura or locoweed. Sit in the middle of the highway at night. Just let the time go by while the seconds accumulated like sand in an open grave.

Abner opened the trunk.

“Damn it. You promised me you’d never make medicine around me, Abner.”

“You don’t believe in it,” Abner smiled back.

“I don’t but I don’t like it, either. I just want to sit down with you and get a buzz on. Like usual.”

“I know what you want to do,” the old man kept smiling. “Too late for that now.”

“Look, we’ll go take a ride. We can shoot some rabbit maybe.”

Abner lifted a blanket from the bottom of the orange crate. Under it was a rabbit in a cage, nose pressed against the slats. Youngman didn’t know Abner to indulge in luxuries like fresh meat. Mostly the old man lived on pan bread, chilis, corn, and maybe a dried peach.

Inside the trunk were what Abner’d always called his “secret goods.” Paho sticks. Feathers. Jars of dried corn, yellow, red, and blue. Abner poured small mounds of the corn on top of the trunk in front of the kachinas.

“It’s just I don’t want them coming after you,” Youngman said, “because they’re going to send me to deal with you. Those people are nuts. They believe your routine.”

From another part of the trunk. Abner rummaged through a Baggie of feathers until he came up with the black-and-white tail feathers of a shrike. He stood a feather in each mound of corn. The effect was of an altar. Abner stepped back to appreciate his handiwork.

“I want to leave the center for the Pahana tablet. Nice, huh?”

“What’s the Pahana tablet?”

“You don’t know?”

“No.”

“You don’t know much, then.” Abner rubbed his hands.

“I know you’re tripping on that dream dust of yours. How much datura did you eat? Tell me.”

“Not much,” Abner shrugged his thin shoulders without turning around to answer. “You’ll need a lot more, Flea.”

Youngman was disappointed. “Making medicine” was the perfect example of a fool’s errand. No amount of “medicine” had yet made a poor, ignorant Indian rich, hip, and white. At least, not in Arizona. As for kachina dolls, everyone knew they were kids’ toys, nothing else.

The row of kachinas stared woodenly back with expressions of painted mischief.

“Yeah. I need a handful of uppers, some speed, a snort of coke, smokin’ acid, and a can of Coors just to start feeling the Spirit.”

“Even so,” Abner maintained, “you’re a good boy.”

Youngman scratched between his eyebrows. There were times when he felt that he and Abner were conversing through an incompetent translator, although they were both using Hopi with the same white corruptions. Mentally, he kicked himself. He shouldn’t have stopped by Abner’s decrepit shack, he should have gone straight on to the Momoa ranch like he was supposed to.

Abner brought out a soda bottle stoppered with aluminum foil. He removed the foil and poured into his palm a kind of sand Youngman had never seen before. It was very fine and black and shiny as eyes. When his hand was full, Abner squatted and, letting a thin stream of the black sand slip between his fingers and thumb, drew a swastika in a corner of the floor. The lines were ruler straight and the angles could have been done with a T-square. Empty, his hand was smudged with oil.

Damn it, Youngman thought. The last thing he wanted to do was arrest the old man.

“You been around the Peabody mine, Abner? That’s not sand.”

“You’re really a good boy. Not too dumb, either.” Abner refilled his hand and started another swastika. “No, it ain’t from Peabody.”

A month before, Abner had been caught dumping cartons of rattlesnakes into the Black Mesa strip mine. The guards would have shot him if Youngman hadn’t arrived in time to make the arrest himself. And then let Abner go.