Read No Way Down, Life and Death On K2 (2010) Online

Authors: Graham Bowley

No Way Down, Life and Death On K2 (2010) (12 page)

He drank water thirstily and sank onto his sleeping bag.

Â

Go Mi-sun's oxygen had finished just after the summit. Then she had had to start breathing the empty frigid air of the high mountain, which provided no energy or warmth at all.

When she reached the end of the Traverse, the line was cut, but she managed to turn down into the Bottleneck. She was surprised at the unusually thin rope playing through her hands but she followed it into the gully. Then, using her two axes, she navigated her way between the icefalls onto the Shoulder.

She was following Kim Jae-soo but by then she could no longer see his light. He was in front somewhere but his headlamp was facing forward.

The forty-one-year-old was a small, stocky, pretty woman, who had grown up in a small town about four hours outside of Seoul. She was single, and she lived in Seoul close to her sister and brother. Bouldering and ice and rock climbing were her main sportsâshe had been an Asian climbing champion for several years and had competed in the extreme sports championships, the X Games, in San Diegoâbut when she got older and put on weight (she had gained twenty-two pounds since 2003, she complained) she switched from sport climbing to mountaineering.

Now the night was especially dark and the wind started to pick up, so she decided to search for shelter from the wind, a large rock or something else that would protect her. Gradually, the realization dawned that she had made a huge mistake. She had lost the route across the spine of the Shoulder and had wandered instead down its sideâprobably the eastern side.

Luckily she hadn't gone too far down, probably a hundred feet or so. She was tough; she knew how to get out of tight situations. Once, on another mountain in the Himalayas, she had fallen 180 feet, shattering a bone in her back; she had been alone but she told herself she was not going to allow herself to die, and over several hours she had managed to crawl down to safety.

Now, laboriously, Go retraced her steps in the dark. But when she got back onto what she thought had to be the main part of the Shoulder, the night was still pitch black and featureless and Go had no idea where she was.

She called out Kim's name in frustration and shouted for help. She walked several yards forward, slowly dropping down the slope. But she was lost again. Rocks reached up on every side of her, black and ugly spikes. She remembered how when she was young and had first gone to the mountains, the leaves were so beautiful. But there was no beauty here, only rocks. The hard stone clunked against her axe. She swung her headlamp around, realizing she had no idea where to go.

Â

After two hours, Chhiring Bhote and Big Pasang Bhote saw a distant light and heard a voice calling for help, and it was then that the two Sherpas saw Go Mi-sun.

She was stuck in rocks some distance from the main route. They shouted to make her understand they had seen her. “Didi!” they called.

“Didi is coming!” she called back.

As they got nearer, however, she pleaded with them to get her down, and they reassured her they were on their way.

When they reached her, one of the Sherpas lifted her shoulders while the other held her legs, and together they carried her out. They tied her safety harness to theirs with a rope and led her down.

When they arrived back at Camp Four after about 4:30 a.m., Kim was lying in his tent, dozing. He woke when the two Sherpas helped Go under the nylon flap. At first, when Kim saw Go's familiar face and realized how late it was, he was angry with his star climber. He cared for her, and she had risked her life. He wanted to know why she had taken so long to climb down. Go, who was still shaken by her experience, bowed her head and apologized, until with relief he comforted her.

Go was surprised when she saw that most of the other tents in the camp were still empty. She was not the last climber from the Flying Jump “A” team to return. Four other climbers were still missing. The battery on the Koreans' radio was not working, so she and Kim could not contact them. The two Sherpas waiting outside might have to continue the search.

Chhiring Bhote and Big Pasang went to their tent to try to rest. They were glad they had found Go, who was a good friend to them. They couldn't sleep, however. They drank water and then stood outside, staring at the mountain.

The night was clear. Headlamps were burning above the Traverse. The serac that had so violently severed the ropes was still active and could yet toss more ice down the Traverse and Bottleneck.

The two Sherpas started packing supplies again. Jumikâtheir brother and cousinâwas out there somewhere.

2 a.m.

J

umik Bhote had led the seven-man South Korean Flying Jump “A” team victoriously from the summit at around 7:10 p.m., carrying 230 feet of rope in his backpack.

Where there was a clear track and the snow was compact and safe, he anchored one end of the rope into the ground with a snow stake and the team members and other climbers plunged down it. The fit Sherpa brought up the rear and then climbed lower with the rope and fixed it in the snow again.

Bhote repeated the maneuver with the rope four or five times, bending and fixing and scurrying down, helped in his labors by Chhiring Dorje, the Sherpa from the American expedition. Eventually, the teams unclipped from the rope and climbed on independently, spreading out in the darkness. On the long snowfield, the two South Korean leaders, Kim Jae-soo and Go Mi-sun, rushed on ahead. As they disappeared into the shadows, Bhote was left alone with the last climbers in the Flying Jump team.

The three men had been so joyful on the summit, Bhote remembered. Before they had left for Pakistan, one of them, Park Kyeong-hyo, a twenty-nine-year-old from a mountaineering club in Gimhae, South Gyeongsang province, had written on the online bulletin board of his mountaineering club: “Now, it's not just a dream anymore. In

some 150 days, we'll be climbing this mountain. Just imagine that. Isn't it fabulous?”

He had been good enough to climb Everest a year earlier, but now Park and the other two climbersâKim Hyo-gyeong and Hwang Dong-jinâlooked like they were dying. None of them said a word. Hwang had been part of the lead group that had left early from Camp Four to fix the rope up the Bottleneck. They just stared at one another dumbly from behind their climbing masks.

Bhote coaxed them onward. He was cold, too, and tired.

Keep going! We must be quick! Please.

At the end of the snowfield, after searching for the way lower for a while, Bhote and the three Koreans dropped down toward the fixed rope that they hoped would lead them into the diagonal around the edge of the serac.

Slowly, they backed down on the ropes toward the Traverse. But after a few yards they stopped.

You have to go!

Jumik shouted.

Finally, dangling on the rope, the three men underneath Bhote seemed unable to climb down another inch, no matter how much he urged them on.

He was worried about how long the rope would hold their weight, or whether there was danger of snow or ice crashing down from above.

Please!

Bhote's voice rang out in the cold darkness on the side of the mountain. He tried to focusâon the rope, the ice face, the lamps of the climbers below himâuntil he felt his own mind drifting away.

Â

In Kathmandu, Jumik Bhote failed his school exit exam and started working on his older brother's fourth-hand family bus on the traffic-clogged streets of the capital, collecting five rupees each from the Nepalese passengers and the tourists traveling to the hotels around

the Kathmandu ring road. After a year or two the bus was so broken down that his brother sold it. Later Bhote signed up as a porter with the South Koreans.

Nawang, the expedition cook, was from the same village as Bhote. He had introduced him to the Flying Jump team, warning him under his breath, “If you work for the Koreans, you have no future.” But the unemployment rate in Nepal was more than 40 percent. This was good work for a poor man from the mountains.

In the spring of 2007, Bhote climbed Everest twice, once with the South Koreans, and became a favorite of Go Mi-sun, who gave him a digital camera. He was proud of that camera.

In the fall, the South Koreans asked him to climb with them on Shishapangma. He was worried about avalanches and he hesitated. No matter what blessings he called down, the gods would be unhappy. Yet by now his father back in Hatiya was dead from a gastric ulcer, his younger brother Chhiring Bhote was living with him in Kathmandu, and three more sisters had already left the countryside for the capital during the Maoist insurgency, in which the rebels had been rounding up anyone from the villages to fight the government. Jumik needed the money.

By now, he also had a partner, Dawa Sangmu, to support. He and Chhiring and their sisters all lived in their older brother's small apartment in the Boudhanath district near the stupa. The apartment had only four rooms, a kitchen, a dining room, a storeroom, and a small bathroom with a squat toilet. There were no beds, only mats, which during the day they packed away in the storeroom. He knew of no other route to success for a young man such as himself in Nepal. He didn't want to be like another brother of his, who had stayed behind in the village and was drinking himself to death on cheap rice wine, and died shortly before Jumik came to K2.

Bhote went to Shishapangma with Kim and the Koreans and it was a triumph. When he returned to Kathmandhu he had been pro

moted to lead Sherpa. To celebrate, Bhote spent $2,000 on a big, black secondhand Yamaha motorbike. Dawa got pregnant. She and Jumik moved into a new apartment, only a single room with a shared kitchen, but it was their own.

He still did not relish climbing in the mountains, but he realized they had been good to him. He took other jobs, guiding a banker from New York on a rapid ascent up Mera Peak in the Hinku valley. He learned a bit of Korean from language cassettes bought from Pilgrim's bookstore in Kathmandu. He took a $250 course in high-altitude climbing at the Khumbu Climbing School outside Namche Bazaar near Everest.

In the spring of 2008, he climbed on Lhotse with his brother Chhiring, and in June, despite last-minute misgivings, they left for K2 with the Flying Jump team.

Now, that all seemed such a long time ago. As he waited in the dark above the three Koreans, Bhote wished he had listened to his instinct. His mind was so distracted by the cold that he wasn't sure what happened next. He didn't know whether there was an avalanche or an icefall or whether the top screw had simply come away from where it was fixed.

The rope dropped suddenly and in a dark, roaring, confusing rush Bhote catapulted past the South Koreans.

He crashed painfully into the ice a little way below them and stopped. He was sprawled against a tiny horizontal ledge, held on the mountain by the rope and his harness.

If it had been an icefall that had caused the rope collapse, it had moved on and the lower screws holding the lines in place had held. Two other climbers were dangling above him.

Bhote was able to sit upright but it was a painful struggle to move: his legs and arms ached from the fall and he was tangled in a welter of rope.

Of the two South Korean climbers hanging above him, the one at the top was suspended headfirst against the ice face. His arms reached out toward Bhote. Bhote wasn't sure who it was, though he could see his bloody face.

The second one also lay head-down against the ice but at a less steep angle. Both of the climbers, he saw, were still clipped onto the rope and hanging in their harnesses, which were supporting them.

Bhote felt that if he struggled he could perhaps have gone on. But he wasn't sure if he could stand, and these men were his clients; he had a duty to stay with them. He was, however, confused. He could not see the third Korean climber. Perhaps he had escaped the rope collapse and had gone on; or perhaps the fall had knocked him completely off the mountain; or perhaps Bhote was mistaken and he was never on the rope and was now somewhere up behind above the serac.

Bhote knew he and the other two men couldn't stay where they were for long. He shouted out, calling for help at first, and then out of sheer panic, but he grew tired. The two trapped Koreans also occasionally shouted for help and moaned. Bhote wanted to reassure them, but the cold crept over him and soon he found he had no strength to speak.

He started to cry. He couldn't feel his hands, and that scared him most, since they were his livelihood. He thought of Dawa Sangmu and Jen Jen in Kathmandu. If he died, he thought, there would be insurance money, wouldn't there? More than $5,000.

But Bhote didn't want to die. He didn't want his family to be mourners, walking to the puja at the Boudha stupa, carrying corn nuts for the monkeys and birds as offerings in his honor.

He imagined them stopping on the way to give one-rupee notes to the beggars at Pashupatinath, most of them grateful but some complaining when the notes were old and wrinkled. He imagined his family bringing fruit for the monks in the stupa circle, jingling money into the monks' pockets and lighting candles, before his brother fell prostrate, wailing Jumik's name. His mother screaming in anguish because she believed his death could have been avoided if only she had been a better mother.

Bhote's mind was wandering. His only hope was that rescuers would climb up from Camp Fourâor that other teams were still making their way down from the summit and would find them.

3 a.m.

M

arco Confortola had waded alone along the sloping snowfield from the top of K2. After more than an hour, he had seen headlamps in a line a few dozen yards below him and had followed behind them. He thought they belonged to the Korean team but their faces were obscured by the bright spotlights of their headlamps, which cast hazy penumbrae in the dark twilight.

Near the steep slope before the lip of the glacier, Confortola drew closer to the other mountaineers. He saw they were from the Korean team, though there was another climber with them who turned out to be the Irishman Gerard McDonnell.

Where are the ropes?

McDonnell shrugged.

The group of climbers searched for the route that would lead them around the crusted edge of the giant serac onto the Traverse but to their mounting frustration they could not find any sign of the ropes.

The end of the snowfield curved down abruptly in front of them, a slope of 30 or 40 degrees. Confortola dragged his tired body to the left and then back to the right on the top of the steep slope, willing himself to find the ropes. The fixed lines had to be down there somewhere, though neither he nor McDonnell felt sure that they were on the same path they had followed on the way up onto the snowfield.

And then, when the Flying Jump team lurched ahead toward the

lip of the glacier and one after the other went over the top, Confortola held McDonnell back. There was something about the look of the snow that made him uneasy.

Both men knew the risks of staying out overnight. It was ten o'clock. They were exhausted. The night was big and black around them. There was no moon and it was fiercely cold, minus 20, easy. Confortola's altimeter wristwatch said they were at 27,500 feet. They had no tent or sleeping bags, no extra food or oxygen. They knew their lives probably depended on descending quickly through the cold to Camp Four.

But they were on a steep slope and they had no idea where they were or where they were going. The lamp at Camp Four winked about half a mile below them, clearly but beyond their reach. Confortola's instinct told him it was no use looking for a way down anymore. They were better off waiting for daylight, when they could see where they were climbing.

“Let's stay here,” he said.

He wanted to be certain that what lay beneath their boots was firm snow and not a crevasse. In addition, there were constant avalanches from these heavy snowfields, big, powerful falls that would crush them if they got caught up in one. Sure enough, minutes later Confortola heard a roll of thunder coming from the serac in front of them, then distant cries and shouts from beneath it. Then silence.

What was that?

I don't know.

Confortola wasn't entirely sure that what he had heard was an avalanche or ice collapsing from the serac but now he felt convinced they were right to stay where they were. They were going to have to bivouac, the term for staying outside without proper shelter under the night sky.

The two climbers sprawled on the steep balcony of snow. McDonnell was wearing his red climbing suit, gray balaclava, and climb

ing goggles. He was tired, Confortola could see. Confortola wanted to make sure he was making the right decision for them both. He wanted a second opinion, so he took out his satellite phone and called Agostino da Polenza, the president of the Italian Everest-K2 committee, and a friend and mentor. Da Polenza was in Courmayeur, Italy. Confortola explained that he felt uncomfortable about the direction they were taking and that they could not find the ropes. He said he had heard what was probably part of the serac falling.

Â

Â

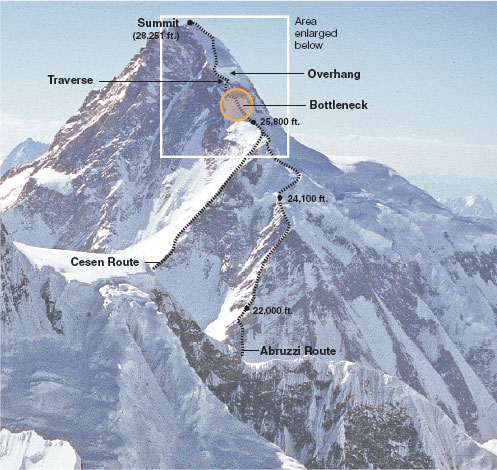

Photographs by Mike Farris (top) and Bruce Normand, courtesy of SharedSummits.com

The two main approaches to the summit of K2, the Abruzzi and Cesen routes, converge at the Shoulder. From there, climbers must navigate the Bottleneck and the Balcony Serac, an overhanging glacier, before reaching the top.

(The New York Times/Michael Farris/Bruce Normand)

Â

On the morning of August 1, 2008, two mountaineers, Marco Confortola and Gerard McDonnell, climb up the Shoulder toward the Bottleneck. In the background is Camp Four, the last camp before the summit. Within a few hours, the crush of climbers at the top of the Bottleneck would lead to the first death.

(Lars Flato Nessa)

Â

Â

Climbers grip fixed ropes to ascend the Bottleneck, a steep and dangerous gully, and then rest before crossing over toward the Traverse. At over 26,000 feet, the expeditions enter the so-called Death Zone, where balance, concentration, vision, and other human body functions break down rapidly under the searing effects of altitude.

(Lars Flato Nessa)

Â

Â

Jahan Baig, a Pakistani high-altitude porter. The HAPs, drawn from northern villages in Pakistan, were employed by foreign expeditions as guides and carriers on the mountain. They were often cheaper alternatives to Nepalese Sherpas.

(Hasil Shah)

Â

The Bottleneck and the steep ice face of the Traverse lead the climbers beneath the overhanging serac, which glistens ominously in the midday sun. In past years, serac collapses sent huge chunks of ice hurtling onto the Traverse and down the Bottleneck. Climbers did not like to imagine what would happen if they got in the way.

(Lars Flato Nessa)

Â