Not Bad for a Bad Lad (2 page)

Read Not Bad for a Bad Lad Online

Authors: Michael Morpurgo

Because I’d been Drum Cupboard Monitor, I

knew exactly where the drum cupboard key was kept, didn’t I? On the hook in the back of the teacher’s desk. So at break time I took the key, opened the drum cupboard and pinched the biggest drum of the lot, my favourite. Then, banging it as loud as I could, and with the whole school watching, I marched through the playground, out of the school gates and down the road. I went on banging that drum all the way home. I got expelled for that, which was all right by me, because without Miss West there I hated the place anyway.

The other schools Ma sent me to after that weren’t much better. The trouble was, they all knew I was a bad lad before I even got there. It’s obvious, isn’t it? They expected me to be a troublemaker and so that’s just what I was, every time. In the end I ran out of schools that would have me. I couldn’t even begin to count the number of times they caned me. It hurt, of course it did. But it was water off a duck’s back to me. By the time I was fourteen I’d left school behind me and found myself a part-time job in a garage, which was all right with me because I liked cars. But at nights I was out on the streets and getting myself into all sorts of trouble and strife.

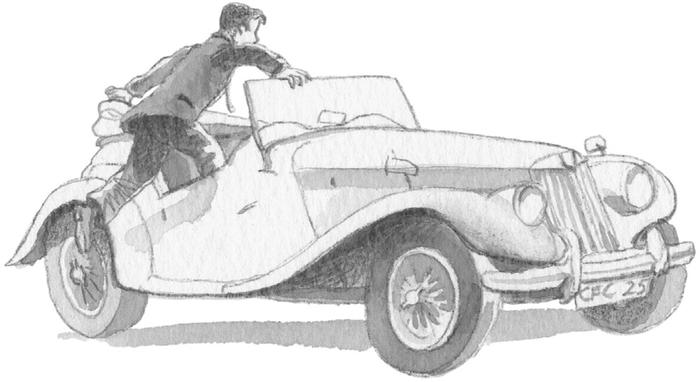

By now I’d got in with a gang of bigger kids and I wasn’t nicking just oranges any more. Anything they could do, I could do better. I had to prove myself, that’s how I saw it. One evening we saw this car parked in the street, a nice shiny-looking MG it was. It wasn’t locked and the driver had left his key in the ignition. Well, I was used to cars, wasn’t I? I knew a little bit about them. So, just to show off to the other kids, I got in and drove it away. Simple.

I roared around the place for half an hour or so, until I hit the kerb and got a puncture. I was just about to get out and leg it, when I saw this pen lying there on the passenger seat – gold topped it was with a gold arrow, very smart, and must be worth a bit too, I thought. So I pocketed it and then got out of there, smartish. Before I went home I flogged the pen

outside

The Horse and Plough, the pub down our street, and for the very first time in my life, I had proper money in my hand. Five shillings I got for it. All right, that’s only twenty-five pence in today’s money, but that was a lot then, a small fortune to me.

Next thing I knew, the police came round to our house that evening to question me. They said

someone

had seen me that afternoon getting out of a stolen car. I told them I’d been at home all the time, and that anyway, I didn’t know how to drive. They went and

searched the house, but they didn’t find anything. I’d hidden my five shillings in the water cistern above the lavvy out the back – y’know, the toilet. They were always out the back in those days.

When they’d gone Ma gave me the rollicking of my life. She took me by the shoulders and shook me till my teeth rattled. She said she knew I’d done it. “You weren’t home this afternoon, were you? You lied, didn’t you? I should have told them, I should have.” She was crying and shouting at the same time, really angry with me she was. “Reform school, Borstal, that’s where you belong. Maybe they can knock some sense into you, because I can’t. You’re nothing but trouble. You can’t be good like other kids, can you? Oh no, you’ve got to go nicking stuff, thieving, lying. Where d’you think that’s going to get you anyway? Crime doesn’t pay. Never did. Don’t you know that? Don’t you know anything?”

Ma was so upset I was worried she might go after the coppers and tell them. But she didn’t, thank

goodness

. So I was in the clear. I’d got away with it. After that, I got away with it again and again. Most of the others in our gang were a lot older than me, and a whole lot better at thieving than I was. But I was

learning fast, all the tricks of the burgling trade: how you choose your house, take your time in staking it out, prise open windows, pick door locks and break into safes. And you had to know who the fences were because you had to get rid of the loot, all the stolen stuff, the incriminating stuff as quick as possible. In only a year or two I was a fully trained thief and a bad lad through and through. But there was one thing I never learned properly: how not to get caught.

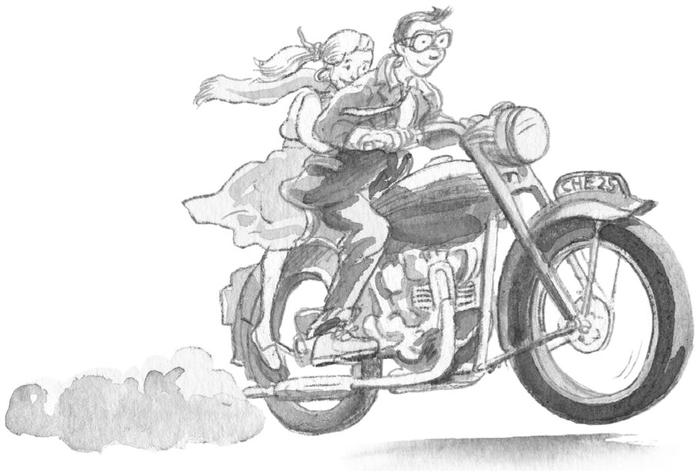

For maybe a year or so, everything looked as if it was working out fine. I was doing very nicely thank you. Who says crime doesn’t pay, Ma? That’s what I was thinking. I had more than enough money to buy anything and everything I wanted: flash suits, flash watch and flash motorbike. I could show-off to

everyone

at home, brag about how well I was doing to

anyone

who would listen. The girls were taking quite a

fancy to me too, and I didn’t mind that either, not one bit. They all thought I was quite a lad. I even bought Ma one of those new-fangled television sets. She was mighty pleased with that, I can tell you. Quite proud of me she was, but that was only because she thought I’d gone back to my old job at the garage, because that’s what I’d told her. She never knew where the money came from, nor what I was getting up to. Mind you, she never asked. Thinking back now, I reckon that might have been because she didn’t

want

to know. She wasn’t stupid, my Ma.

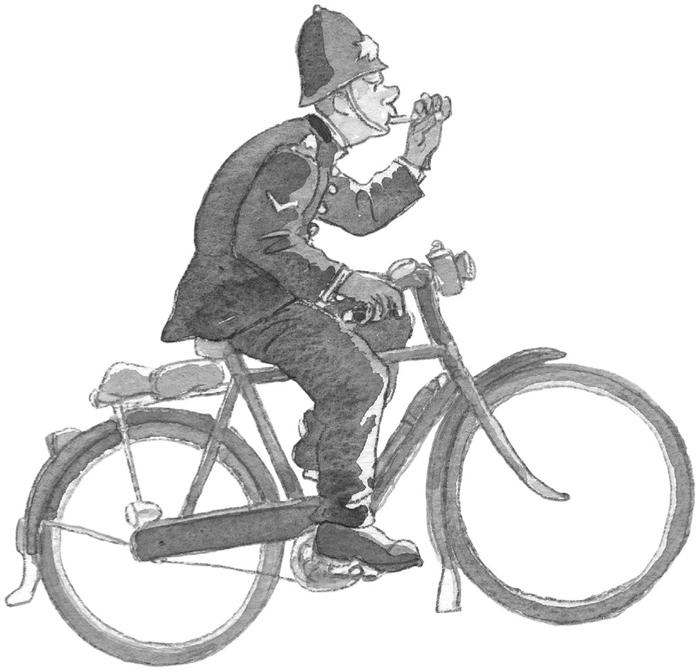

Then one night my luck ran out. I’d done a good clean job, in and out of an empty house, quiet as a mouse, no one there, no bother. I’d nicked some

silver

and some jewellery, nice stuff too. Everything seemed tickety-boo. But as I was coming away from the house I saw this copper riding towards me on his bike. I should have just walked on by – he wouldn’t have even noticed I was there. But oh no, I had to go and make a run for it. First rule in the book: always walk away from a job, never run. He blew his whistle and I was off down the road, going like a greyhound.

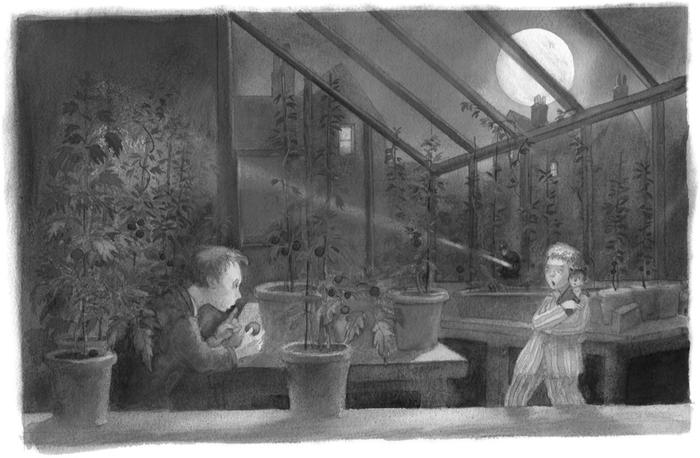

He chased after me, over a building site, across a railway line. I chucked away all the stuff I’d pinched. Lose the evidence, that’s what I was thinking, but I couldn’t lose him. In the end, I scrambled over the wall into someone’s back garden, and then I saw this greenhouse. So I dived in there, nifty as you like, and hid myself in amongst a whole forest of tomato plants. For a while there was a lot of shouting and dancing torchlights out there, but then it all went quiet. It was just me and a big round moon up there and tomatoes all around me. I thought I’d just lie low for a bit, until things calmed down, until I was quite

sure I was in the clear.

Half an hour or so later I was still sitting there in the greenhouse, happily scoffing down a nice ripe tomato, when I looked up and saw this little boy standing there in his striped pyjamas.

“That’s one of my dad’s tomatoes,” he said. “That’s stealing, that is. You’re the one the coppers were after, aren’t you? You’re a bad’n, I know you are.”

And then, before I could stop him, he ran for it, shouting his head off. In no time at all there were coppers everywhere and they took me away. I got sentenced to a year in Borstal for breaking and

entering.

It would have been more if Miss West hadn’t come and spoken up for me.

It was very kind of her, but I felt so ashamed of myself when I saw her coming into the court. I

couldn’t

bring myself to look at her properly.

The magistrate told me just what he thought of me. “You’ve been a bad lad, haven’t you?” he said. “However, your old teacher, Miss West, tells us you’re not a bad lad at heart and I’m inclined to

believe

her, to give you the benefit of the doubt. But you have been stupid, that’s for sure, and you’ve got yourself in with the wrong sort.” He leaned forward and looked at me over his glasses. “You’ve wasted your life up until now, young man,” he went on. “You’re only sixteen, still young. You can make a fresh start. You can put things right if you want to. It’s up to you. You’ll have a year in Borstal to think things over, to learn your lesson. Take him away.”

Silly old goat, I was thinking. But I knew in my heart of hearts, even as I was thinking it, that I was the silly one, not him.