Notebooks (22 page)

Authors: Leonardo da Vinci,Irma Anne Richter,Thereza Wells

Tags: #History, #Fiction, #General, #European, #Art, #Renaissance, #Leonardo;, #Leonardo, #da Vinci;, #1452-1519, #Individual artists, #Art Monographs, #Drawing By Individual Artists, #Notebooks; sketchbooks; etc, #Individual Artist, #History - Renaissance, #Renaissance art, #Individual Painters - Renaissance, #Drawing & drawings, #Drawing, #Techniques - Drawing, #Individual Artists - General, #Individual artists; art monographs, #Art & Art Instruction, #Techniques

O excellent thing, superior to all others created by God! What praises can do justice to your nobility? What peoples, what tongues will fully describe your function? The eye is the window of the human body through which it feels its way and enjoys the beauty of the world. Owing to the eye the soul is content to stay in its bodily prison, for without it such bodily prison is torture.

5

5

O marvellous, O stupendous necessity, thou with supreme reason compellest all effects to be the direct result of their causes; and by a supreme and irrevocable law every natural action obeys thee by the shortest possible process. Who would believe that so small a space could contain the images of all the universe? O mighty process! What talent can avail to penetrate a nature such as these? What tongue will it be that can unfold so great a wonder? Verily none! This it is that guides the human discourse to the considering of divine things. Here the forms, here the colours, here all the images of every part of the universe are contracted to a point. What point is so marvellous? O wonderful, O stupendous necessity—by thy law thou constrainest every effect to be the direct result of its cause by the shortest path. These are miracles . . . forms already lost, mingled together in so small a space it can recreate and recompose by expansion. Describe in thy anatomy what proportion there is between the diameters of all the lenses (

spetie

) in the eye and the distance from these to the crystalline lens.

6

spetie

) in the eye and the distance from these to the crystalline lens.

6

The eye whereby the beauty of the world is reflected is of such excellence that whoso consents to its loss deprives himself of the representation of all the works of nature. The soul is content to stay imprisoned in the human body because thanks to our eyes we can see these things; for through the eyes all the various things of nature are represented to the soul. Whoso loses his eyes leaves his soul in a dark prison without hope of ever again seeing the sun, light of all the world; How many there are to whom the darkness of night is hateful though it is of but short duration; what would they do if such darkness were to be their companion for life?

7

7

The air is full of an infinite number of images of the things which are distributed through it, and all of these are represented in all, all in one, and all in each. Accordingly if two mirrors be placed so as to exactly face each other, the first will be reflected in the second and the second in the first. Now the first being reflected in the second carries to it its own image together with all the images reflected in it, among these being the image of the second mirror; and so it continues from image to image on to infinity, in such a way that each mirror has an infinite number of mirrors within it, each smaller than the last, and one inside another. By this example it is clearly proved that each thing transmits its image to all places where it is visible, and conversely this thing is able to receive into itself all the images of the things which are facing it.

Consequently the eye transmits its own image through the air to all the objects which face it, and also receives them on its own surface, whence the ‘sensus communis’ takes them and considers them, and commits to the memory those that are pleasing.

So I hold that the invisible powers of imagery in the eyes may project themselves to the object as do the images of the object to the eyes.

An instance of how the images of all things are spread through the air may be seen if a number of mirrors be placed in a circle, and so that they reflect each other for an infinite number of times. For as the image of one reaches another it rebounds back to its source, and then becoming smaller rebounds again to the object and then returns, and so continues for an infinite number of times.

If at night you place a light between two flat mirrors which are a cubit’s space apart, you will see in each of these mirrors an infinite number of lights, one smaller than another in succession.

If at night you place a light between walls of a room every part of them will become tinged by the images of this light, and all those parts which are directly exposed will be lit by it. . . . This example is even more apparent in the transmission of solar rays, which pass through all objects and into the minutest part of each object, and each ray conveys to its object the image of its source.

That each body alone of itself fills all the surrounding air with its images, and that this same air at the same time is able to receive into itself the images of the countless other bodies which are within it, is proved by these instances; and each body is seen in its entirety throughout the whole of this atmosphere, and each in each minutest part of it, and all throughout the whole and all in each minutest part; each in all, and all in every part.

8

8

If the object in front of the eye sends its image to it, the eye also sends its image to the object; so of the object no portion whatever is lost in the images proceeding from it for any reason either in the eye or the object. Therefore we may rather believe that it is the nature and power of this luminous atmosphere that attracts and takes the images of the objects that are within it, than that it is the nature of the objects which send their images through the air. If the object opposite the eye were to send its image to it, the eye would have to do the same to the object; whence it would appear that these images were incorporeal powers. If it were thus it would be necessary that each object should rapidly become smaller; because each object appears by its image in the atmosphere in front of it; that is the whole object in the whole atmosphere and all in the part; speaking of that atmosphere which is capable of receiving in itself the straight and radiating lines of the images transmitted by the objects. For this reason then it must be admitted that it is the nature of this atmosphere which finds itself among the objects to draw to itself like a magnet the images of the objects among which it is situated.

Prove how all objects, placed in one position, are all everywhere and all in each part.

I say that if the front of a building or some piazza or field which is illuminated by the sun has a dwelling opposite to it, and if in the front which does not face the sun you make a small round hole all the illuminated objects will transmit their images through this hole and will be visible inside the dwelling on the opposite wall which should be made white, and they will be there exactly, but upside down; and if in several places on the same wall you make similar holes you will have the same result from each.

Therefore, the images of the illuminated objects are all everywhere on this wall and all in each minutest part of it. The reason is this—we know clearly that this hole must admit some light to the said dwelling and the light admitted by it is derived from one or many luminous bodies. If these bodies are of various shapes and colours the rays forming the images are of various colours and shapes and the representation on the wall will be of various colours and shapes.

9

9

The circle of light which is in the centre of the white of the eye is by nature adapted to apprehend objects. This same circle contains a point which seems black. This is a nerve bored through, which penetrates to the seat of the powers within where impressions are received and judgement formed by the ‘sensus communis’.

Now the objects which are over against the eyes send the rays of their images after the manner of many archers who aim to shoot through the bore of a carbine. The one among them who finds himself in a straight line with the direction of the bore of the carbine will be more likely to hit its bottom with his arrow. Likewise of the objects opposite to the eye those will be more directly transferred to the sense which are more in line with the perforated nerve.

That liquid which is in the light that surrounds the black centre of the eye acts like hounds in the chase, which start the quarry for the hunters to capture. Likewise the humour that is derived from the power of the

imprensiva

and sees many things without seizing hold of them, suddenly turns thither the central beam which proceeds along the line to the sense and this seizes on the images and confines such as please it within the prison of its memory.

10

imprensiva

and sees many things without seizing hold of them, suddenly turns thither the central beam which proceeds along the line to the sense and this seizes on the images and confines such as please it within the prison of its memory.

10

All bodies together, and each by itself, give off to the surrounding air an infinite number of images which are all in all and all in each part, each conveying the nature, colour, and form of the body which produces it. It can clearly be shown that all bodies pervade all the surrounding atmosphere with their images all in each part as to substance, form, and colour; this is shown by the images of many and various bodies which are reproduced by transmittance through one single perforation, where the lines are made to intersect causing the reversal of the pyramids emanating from the objects, so that their images are reflected upside down on the dark plane (opposite the perforation).

11

11

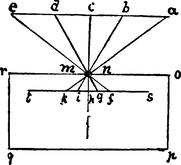

An experiment, showing how objects transmit their images or pictures, intersecting within the eye in the crystalline humour.

This is shown when the images of illuminated objects penetrate into a very dark chamber by some small round hole. Then you will receive these images on a white paper placed within this dark room rather near to the hole; and you will see all the objects on the paper in their proper forms and colours, but much smaller; and they will be upside down by reason of that very intersection. These images, being transmitted from a place illuminated by the sun, will seem as if actually painted on this paper, which must be extremely thin and looked at from behind. And let the little perforation be made in a very thin plate of iron.

Let

abcde

be the objects illuminated by the sun and

or

the front of the dark chamber in which is the hole

nm

. Let

st

be the sheet of paper intercepting the rays of the images of these objects and turning them upside down because since the rays are straight

a

on the right becomes

k

on the left, and

e

on the left becomes

f

on the right; and the same takes place inside the pupil.

12

abcde

be the objects illuminated by the sun and

or

the front of the dark chamber in which is the hole

nm

. Let

st

be the sheet of paper intercepting the rays of the images of these objects and turning them upside down because since the rays are straight

a

on the right becomes

k

on the left, and

e

on the left becomes

f

on the right; and the same takes place inside the pupil.

12

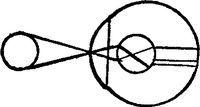

Necessity has provided that all the images of objects in front of the eye shall intersect in two planes. One of these intersections is in the pupil, the other in the crystalline lens; and if this were not the case the eye could not see so great a number of objects as it does. . . . No image, even of the smaller object, enters the eye without being turned upside down; but as it penetrates into the crystalline lens it is once more reversed and thus the image is restored to the same position within the eye as that of the object outside the eye.*

13

13

It is impossible that the eye should project from itself, by visual rays, the visual power,* since as soon as it opens, the front portion (of the eye) which would give rise to this emanation would have to go forth to the object, and it could not do this without time. And this being so, it could not travel so high as the sun in a month’s time when the eye wanted to see it. And if it could reach the sun it would necessarily follow that it should perpetually remain in a continuous line from the eye to the sun and should always diverge in such a way as to form between the sun and the eye the base and the apex of a pyramid. This being the case, if the eye consisted of a million worlds, it would not prevent its being consumed in the projection of its power; and if this power would have to travel through the air as perfumes do, the winds would bend it and carry it into another place. But we do (in fact) see the mass of the sun with the same rapidity as (an object) at the distance of a braccio, and the power of sight is not disturbed by the blowing of the winds nor by any other accident.

14

14

Other books

Drag-Strip Racer by Matt Christopher

Diner Impossible (A Rose Strickland Mystery) by Austin, Terri L.

A Fatal Winter by G. M. Malliet

Saving All My Lovin' by Donna Hill

Before the Darkness (Refuge Inc.) by Leslie Lee Sanders

Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution by Laurent Dubois

Laird of the Highlands: International Billionaires IX: The Scots by Caro LaFever

The Rain Before it Falls by Jonathan Coe

Jealousy by Lili St. Crow

1 Killer Librarian by Mary Lou Kirwin