Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (13 page)

Read Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War Online

Authors: Viet Thanh Nguyen

So it is that the rest of the world looks with horror at Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge and wonders how the genocide happened, when the reality is that it could have happened anywhere with the right “inhuman conditions,” to steal Pheng Cheah’s title. Cheah’s thinking illustrates the poststructuralist tendency in one branch of the humanities, which Panh departs from. Cheah, like his influencer, Foucault, argues that it is a mistake to think of the human and the soul as being divine creations. Instead, they are created by power and should be seen as effects of power. This power is not human in the sense that it is not wielded completely by any individual. Power exceeds individuals, and we are subject to it. This is the inhuman condition, according to Cheah. Derrida also influences Cheah, and in a typically Derridean reversal, Cheah argues that the inhuman precedes the human, not the other way around. In conventional thinking, inhumanity is a deformation of an original humanity, which is what leads to the usual sentimental, humanist hand-wringing over the inhuman behavior of various individuals, tribes, parties, and nations. For Cheah, to insist on the priority of humanity is a fundamental misrecognition, leading to a focus on the inhuman as a moral aberration instead of as a condition for humanity. But while Cheah is not interested in the more mundane, moral notion of the inhuman, Panh insists that it is impossible to think of the inhuman only on the philosophical terms that Cheah proposes.

While it is critical to recognize inhumanity as an outcome of civilization and its privileging of the human, one must also confront the inhuman in terms of individual culpability and action, as a deformation of the human, as a question of responsibility that cannot be deflected by a turn to the structuring force of power. For Cambodian society in general, horror consists not only of being victimized but also of victimizing others. To speak of Cambodians in this way is not to deny history or power: the responsibility of the French in colonizing Cambodia, the Americans in bombing the country, the North Vietnamese in extending their war through the country, or the Chinese in supporting the Khmer Rouge even with knowledge of their atrocities. To speak of Cambodians as bearing widespread responsibility for the genocide is not to point to them as culturally unique in their ability to commit murder or allow it to happen. As the writer W. G. Sebald points out regarding Germans, “it’s the ones who have a conscience who die early, it grinds you down. The fascist supporters live forever. Or the passive resisters. That’s what they all are now in their own minds … there is no difference between passive resistance and passive collaboration—it’s the same thing.”

43

What is perhaps unique is that unlike the German or other instances of mass murder, Cambodians of the ethnic majority who killed each other or witnessed each others’ deaths wore the same (ethnic) face. So it is that Cambodians cannot solely blame their crimes on the incitement of outsiders or (ethnic) others, which compels them to look at themselves as one reason for what happened, a task they may have a hard time doing.

The Khmer Rouge rendered others inhuman in order to destroy them with inhuman behavior, but in the aftermath of their rule most of those differences disappeared, leaving it clear that those others were not really other, if we speak only of the ethnic majority. For Panh, Duch is the face of this situation, where the line between human and inhuman has been crossed, as it was for the rest of the former Khmer Rouge, now embedded too deeply in Cambodian society to be extricated easily. But between victim and victimizer exists a population in between—the complicit, the witness, the bystander, the resigned. The Khmer Rouge invoked this population as the reason for their cause—peasants exploited by French colonization and Cambodian hierarchy, then bombed by American planes and misled by the Khmer Rouge. Panh points out that they are still poor. If they were not on the side of justice during the Khmer Rouge era, they are also people for whom justice has not been done in the years afterward. Their situation is absurd, horrible, a low-level and continuous crime that has lasted centuries.

Does Duch laugh because he sees this absurdity? “I could hardly believe it—it was too beautiful, too easy: Laughter bursts out in the midst of mass crime. Duch has a ‘full-throated’ laugh: I can’t think of another way to describe it.”

44

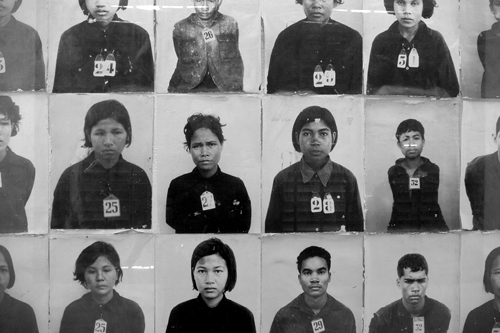

Strangely enough, a laughing face stands out amid all the faces of the dead and the soon to be dead at S-21. It seems inexplicable that anyone could laugh in this place, the most disturbing museum or memorial I had ever visited, including the extermination camps of Europe. This is a drawn face, not a human face, the slash through its laughing visage the universal sign of prohibition, here commanding the visitor not to laugh. The sign itself says

Keep silent

. Sign and face testify that someone has laughed here, and not just Duch. While I was there, teenage foreign tourists laughed in the corridor of the isolation cells. Why do some visitors laugh? Out of nervousness, perhaps, for if one is a foreigner visiting this place during one’s lunch break or on holiday, what is one supposed to say? Or if one is local, perhaps the laughter covers up the tears or the disbelief, a polite way of hiding how distraught or uncomfortable one may be. Perhaps what the laughter mocks is not the dead, but the authority embodied in memorials. This authority is pedagogical, and who has never wanted to laugh at authority and pedagogy? This authority trains visitors in the proper etiquette of memory and mourning. This authority says that

this is not a laughing matter

and to

always remember

and

never forget

. This authority wants us to forget its own power, and how the crimes recorded by these memorials were not committed by monsters and enemies of the state. These crimes were committed by humans whose deeds would have been lionized if their state and side had triumphed. Although laughter may not be a polite response, even an inhuman one, it is possibly understandable, aligning the one who laughs with the devil’s subversion, as Kundera claims in

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

. The laughter of angels, he says, is the sound of those in power. But should one always be aligned with the angels? Rather than just believe that devils are fallen angels, might it not be the case that angels are triumphant devils?

45

In the terms of Levinas, the face of the Other calls out for goodness and for justice, demanding that “You shall not commit murder,” especially against what he calls the Stranger.

46

In his quasi-religious language—the Other exists on high, in God’s realm, in infinity

47

—Levinas is on the side of the angels, feeling sympathy for the Stranger rather than the Devil, looking down on an earthbound totality where warfare and imperialism are the law of the land. He wills himself to believe in his ethics, in the idea that “to be for the Other is to be good.”

48

But he concedes that “the Other … is situated in the region from which death, possibly murder, comes.”

49

When the Khmer Rouge arrived triumphantly in Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, they were strangers and others to the city’s population. If everyone on all sides treated their others as if they themselves wore the face of the Other, then perhaps the ethical and moral goodness called for by Levinas would be achieved. But the others who were the Khmer Rouge brought death, and who is to say that the face of the Other worn by them was not just as real as the one Levinas longs for? What if the face of the Other heralded not justice but terror? In our contemporary wars waged for and against radical Islam, could the masked face of the terrorist be the face of the Other to the West? What if justice and terror were one and the same? The Khmer Rouge and the radical Islamists certainly believe that they are on the side of justice, as do the Western states with their beliefs in tolerance, free speech, freedom of religion, and airpower.

No wonder that some philosophers, like many other people, turn away from the possibility of hell and resort to faith in heaven, the future that is yet to come. The philosophical equivalent of faith is the secular belief that the Other compels us to justice (which, in poststructuralist thinking, need never be defined). If we wish to live as a species, we need to hold on to that faith, but we also need to confront our doubt. It is possible that the Other is a killer, and that we ourselves may be killers or complicit in killing. If so—and if Duch is simply another case of the “banality of evil,” the term Hannah Arendt coined to speak of the Nazi Adolf Eichmann—the lesson to be learned from Duch’s example is that the banality of evil has generally been reserved by the West for itself, as a sign of subjectivity, of agency, of centrality, even for the most unimportant of Westerners who functioned as nothing more than cogs in the war machine. Excluding others from the banality of evil denies them that same right to subjectivity found in villianous behavior. In contrast, to make others the subject of the banality of evil is to renounce the patronizing pity of the West, which is tempting for others to themselves assume. Pitying oneself, for others, is always detrimental, for those who believe that they cannot do evil will in the end do evil, which is what happened in Cambodia and in many nations that threw off Western domination.

To put this ethical conundrum of the Other in the most schematic way possible, here is how the various modes of ethical memory work. In the ethics of remembering one’s own, the simplest and most explicitly conservative mode, we remember our humanity and the inhumanity of others, while we forget our inhumanity and the humanity of others. This is the ethical mode most conducive to war, patriotism, and jingoism, as it reduces our others to the flattest of enemies. The more complex ethics of remembering others operates in two registers, the liberal one where we remember our humanity and the radical one where we remember our inhumanity. In both registers, we remember the humanity of others and forget their inhumanity. The liberal register where we remember our humanity is also conducive to war, although war usually carried out in humanitarian guises, as rescue operations for the good other (which may require us killing, with great regret, the bad other). The more radical version, where we remember our inhumanity, is the driving force behind antiwar feeling, as we worry about the terrible things we can do. And yet there is a level of deception in this radical register, too, for if we also see only the humanity of others, and not their inhumanity, we are not seeing them in the same way we see ourselves. So it is that in the name of the other’s humanity, we consign the other to subordinate, simplified, and secondary status in contrast to our more complex selves. While we are capable of dying and killing, of tragedy and guilt, of the whole panoply of human and inhuman action and feeling, the other is only capable of being killed, perpetually pegged as an object of our seemingly well-intended pity. To avoid simplifying the other, the ethics of recognition demands that we remember our humanity and inhumanity, and that we remember the humanity and inhumanity of others as well. As for what this ethics of recognition asks us to forget—it is the idea that anyone or any nation or any people has a unique claim to humanity, to suffering, to pain, to being the exceptional victim, a claim that almost certainly will lead us down a road to further vengeance enacted in the name of that victim. The fact of the matter is that however many millions may have died during our particular tragedy, millions more have died in other tragedies no less tragic.

Rithy Panh’s memoir and films foreground this ethics of recognition and make a daring claim: Cambodia belongs in the center of world history because of the humanity and the inhumanity of the Khmer. This is an important claim for two reasons. The first and most obvious reason is simply that the claim moves Cambodia and the Khmer people from margin to center. This is also the less interesting reason, given that making the marginalized more visible leaves the periphery intact for new others to inhabit. The more important reason is the assertion of inhumanity, for the other’s move from margin to center in Western discourse is most often premised on asserting the other’s humanity. By rejecting this sentimental, heartwarming reasoning, Panh’s work affirms the importance, and the difficulty, of grappling with inhumanity, both the inhumanity of the West and the inhumanity of its others (which is to say, from the perspectives of those others, us). The face of the Other is thus, even in its name, a misnomer. It tempts us to pity others, to see only the singular face of their suffering. In reality, the Other always has at least two faces, human and inhuman.