Of Moths and Butterflies (21 page)

Read Of Moths and Butterflies Online

Authors: V. R. Christensen

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #Literary, #Romance, #General

“We’ll go when you are ready, then,” Muriel had said, relenting, though only out of desperation. It was clear Imogen would not be forced, but it was apparent by her too ready dismissal, her refusal to commit to the promise, that she intended to put off the visit indefinitely. Muriel would see the house one way or another, though. She was quite determined.

December 1881

LTHOUGH IT HAD

LTHOUGH IT HAD

been agreed that Imogen was to step back into Society, it was a week or two more before she was actually allowed to do so. In the interim, her time was spent in anxious anticipation, which made the tedium of her daily schedule all the harder to bear. Her aunt’s manner toward her began to grate as well. Muriel was gentle and patient in her daily dealings with her niece, but when certain topics of discussion were broached—her uncle’s house, her suitability for Society, and, most provoking of all, Roger—her manner became more strained, and it was clear in the way that her gaze became icy while her voice remained sugar sweet, that Muriel’s efforts at civility were in conflict with her natural inclinations. Even had her performance been more convincing, Imogen’s experiences did not allow for much naïveté. She was not quite so foolish nor so desperate in her self-love as to believe that every soft word spoken was sincerely and selflessly uttered. Her history had taught her to see those honeyed words as inconsistencies and ones that should raise suspicion before exciting vanity.

Still, Muriel was not quite without cause to hope, for though Imogen could not be courted by kindness, to convince her that she was unworthy of whatever happiness she might ordinarily hope to gain was far too easily accomplished. Imogen believed quite thoroughly in her own unworthiness, and she would not again try for escape as she had done before. Her sojourn had been a lesson in futility. But it had also given her strength. She would endure, and she would hold on for dear life to that which might, should heaven answer her prayers, offer her last and perhaps only chance at happiness. One way or another, she would claim her right to a life of her own.

* * *

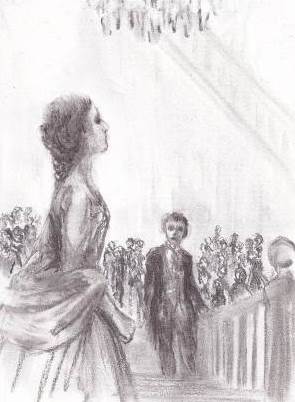

At last the evening of her first outing came. They arrived at the dinner party early enough to allow Imogen the opportunity of reacquainting herself with a few of her distant cousins, from whom she had long since been estranged. Close friends of the family were also present, and in order to mitigate any discomfort Imogen might feel under such awkward circumstances, Julia, with Lara in tow, took her niece under her wing. Imogen could not have known the measure of her aunt’s popularity, never having witnessed it before now. Her power tonight was used to influence others, that her example might be followed in welcoming the companionship that she was so proud of in her niece. It was not all easy work however. There were many whose disinclination to become better acquainted was apparent, and the more the room filled, the more alone Imogen began to feel in it. Even with the silent and ever pre-occupied Aunt Lara beside her.

If only Roger were here, she might then be able to endure it. But he was not. Nor was she surprised to learn that he was attending upon other engagements this evening. She had not seen him again since their reunion, and Muriel’s petitions that she ought not to think of him had grown increasingly frequent. But those admonishments had not the effect her aunt had supposed, for in her loneliness, in her need for companionship, Imogen clung to the idea of him. And it was an escape of sorts, for it pushed the memory of another from her mind. She was not likely to see Mr. Hamilton again. The certainty of it, made her regret. But there was nothing to regret. At least she was foolish to do it. And so she replaced these thoughts with those of another. One who loved her like no other had ever done.

As she meditated, watching the crowd as it took turns watching her, discussing her, weighting the chances of her success (or failure) she struggled to find some glimmer of hope to cling to. There was only one way to do it. She thought of Roger and what he might do for her when once he found a way around her aunt’s contrivances to keep them apart. She knew he would, eventually.

Through dinner, she sat still and silent, receiving as much attention as might a figure of naked Hebe. Everyone aware of her presence, no one daring to be seen considering her. Yet the whispers and the surreptitious glances continued. Imogen bore it all, as she was expected to do, with perfect equanimity.

Dinner this night, and on each evening subsequent, was followed by entertainment. Games, cards, music, or, on occasion, to both her delight and dismay, dancing was the order of the evening. On such nights as music played and couples formed, Imogen was made to quit the party early, before the temptation toward any too frivolous merry-making should overcome her. She envied the couples, admired the exercise, but knew (and her aunt did not spare herself in reminding her) that these diversions were not hers to enjoy. She was still in mourning, after all, though half-mourning, at that. And she had no desire to set herself up for further humiliation. By now she had had her fill of company, at any event, and was grateful for any excuse to get away.

If the joint aim of her aunts was to assure themselves of their niece’s acceptance into their social circle, the sheer frequency of her engagements over the following weeks should have provided for it. But such endeavours seemed not to bear the kind of success Imogen, or her aunts, had hoped for. She wished to blend in, to become a fixture, unnoticed but not unwelcome. It was not to be. Without someone to bear her burdens proudly alongside her, her chances were non-existent. Julia could only be presumed upon so far. She wanted, needed, Roger.

Imogen, desperate for some companionship, for

his

companionship, at last summoned the courage to ask after him, and to inquire as to when she might be allowed to see him again.

“You should know, Imogen, that Roger’s prospects are looking well for him,” Muriel said as they prepared for yet another evening out.

Imogen clasped her aunt’s necklace and then looked at her in the reflection of the dressing table mirror. That it ought to have been Muriel helping Imogen to dress had not occurred to either of them.

“I don’t doubt it,” Imogen said in reply.

Muriel arranged the newly placed gems to lay neatly at her throat and examined herself, and then her niece, in the mirror. “You would not want to get in the way of his chances.”

Imogen remained silent, dreading what seemed destined to come next.

“We go tonight to the home of the young lady in whom he has recently, and wisely, placed his hopes.”

The disappointment she felt surprised even her. Imogen stared blankly into the mirror, and saw nothing.

“He could not seriously consider you. You know that?”

Imogen blinked, waking. “Yes, I do know,” she heard herself say. What had she been thinking? Of course it was true. And then considering further, and reconsidering her desire to go out at all or ever, “He will be there, though? You are sure of it?”

“Considering all, I expect he will,” Muriel said as though Imogen were foolish even to ask. Perhaps she was.

Her aunt turned to look at her, and taking her hand, spoke sweetly—too sweetly. “It will be difficult for you, my dear, to find someone willing to look past your faults, but think of all you have on your side. The money makes up for a great deal.”

Imogen paled and tried to recover her courage which had scattered and flown like tares in the wind. While she did so, or struggled to do so, and without success, Muriel finished the last of her preparations and was soon ready.

* * *

Imogen, certain an hour ago that all she wanted in the world was to see Roger, entered the house of Miss Hermione Radcliffe with the desire only of leaving it again as early as she might be allowed. As had become the pattern of these evenings, she, accompanied by Lara, took a pass of each of the rooms before finding for themselves an out of the way place where they might while away the time. She was glad, on this evening more than ever, to do it.

By now certain details of her life and history had begun to be handed about. Some false. Others quite accurate. She had run away from her cruel uncle and had come back disappointed. She had engaged upon an elopement, but had been rescued just in time. She had run away with a fortune stolen from her uncle’s house. She had run away

from

a fortune. But no. That was inconceivable. And the looks and curious stares continued. She was a curiosity, to be sure. The ladies who sought her company did so with a mixture of shocked interest and fascination. They wished to know her story; what was true, what was not. She told them nothing, and they were soon enough on their way. But the gentlemen… The gentlemen persevered, their conversation trite and trivial beyond endurance. She answered their questions vaguely, and when she could bear no more, she fanned herself impatiently and prodded Lara to steer the conversation onto more reciprocally tedious paths. Lara would begin, then, and seemingly with great pleasure, upon recollections of her youth, parties like these, where she was the debutante whose affections were to be sought and won. She laughed and flirted—even with gentlemen half her age, and took great pleasure in it, too. When Imogen turned her attention away, and Lara’s laughter and triviality became too much, these would-be suitors at last understood that their time was up and their chance passed. This was not the way to improve her popularity, Imogen well knew, but she had little patience for such blatantly mercenary efforts. And they must be, to the very last man, mercenaries all, to consider her in spite of the talk.

She had just determined to go in search of Muriel with the hope of departing early, when Julia came to find her. “Roger is here, Imogen. He’s anxious to see you. Will you let me take you to him?”

The elation she felt at the prospect of seeing him—that he wanted to see her—could not be quailed or disguised. “May I, aunt?” she found herself asking of Lara.

“Oh yes!” said Lara, and then stopped. “Oh, no!” and looked to Julia helplessly.

“Muriel has told you, I suppose,” Julia said, turning to her sister, “that you are to shield Imogen from Roger?”

“Yes, yes,” she answered.

“But think, Lara. If Roger welcomes her openly, others will follow, and that is why she has come. Your job is to shield her from those whose company she finds unwelcome. Or those whom you might deem unworthy. You can do that, surely?”

Lara looked to Imogen then, as if considering. She blinked. “What do you think, dear? Would you like to see him?”

“I would like it above all things, Aunt. If you would be so good as to allow it.”

“Then you must,” Lara said. “Go to him, dear. He’ll be quite happy to see you, too, I’m sure.” Thus rescued from her confusion, she released her charge to her sister.

* * *

Archer, on this evening, arrived much later than would have been his desire. He’d at last been released from the confines of his uncle’s library, to which he had been relegated nearly the moment he’d pronounced his intentions to return to Town. Trivial tasks he’d been assigned. And those not so trivial. He’d been directed to examine the last several years’ ledgers, and had done so—at first grudgingly and, later, upon realising the purpose, with an air of resentful resignation. His uncle’s financial affairs—and consequently his own—were far more troublesome than he had ever supposed. He had always known there were debts; he had never realised the extent of them. Despite the hardship, Archer’s education had been a significant expense. There were his living expenses, too, to consider. In addition, there was all that it required to run the house, to pay the staff’s wages and to keep up the necessary appearances. These things added up. And on top of it all were the recent improvements and the employment of a maid they could not reasonably afford to pay. Long hours he had spent at the books, counting, recounting, calculating, trying to make it work out by any means other than the most obvious. Certainly Sir Edmund might marry Mrs. Barton. Her widow’s fortune would relieve them of the greater weight of their burden—for a time. But it would not last. What they needed was something far more significant. It was Archer’s responsibility to make up for these shortcomings. He had always known it. Why had he thought he could escape duty?

Perhaps Miss Shaw’s departure was timely. What he had proposed to do, and had very nearly determined to do, would ruin him and his uncle at once. He could not think of it now. His desires had been irrational. Perhaps on the very brink of insanity, for it could only have ended in disaster. With his nose buried in the ledger, with his mind full of numbers and calculations, plans and schemes both worthwhile and worthless, he endeavoured to forget. And in a stupor of mind numbing facts and figures, and these mingling amidst the effects of some very good brandy, he’d come to convince himself he’d done it.