Old Songs in a New Cafe (8 page)

Read Old Songs in a New Cafe Online

Authors: Robert James Waller

At Dinjan, he and the other pilots slept and took their meals in a large bungalow on the fringe of a tea plantation. Well

before dawn, he was awakened by the hand of a servant boy. Now he stands drinking thick Indian tea on the veranda, looking

out toward the jungle where leopards sometimes go.

An open four-wheel-drive command car arrives, and he rides through the heavy night toward an airfield five miles away. Time

is important now, in this early morning of 1943. Since losing an airplane to Japanese fighters over the Ft. Hertz Valley,

the pilots cross there only in darkness or bad weather when the fighters are grounded. He signs the cargo manifest, checks

the weather report, and walks out to the plane.

Like delicate crystal, our liberties sometimes juggle in the hands of young men. Boys, really. Climbing to the top of the

arch at the front of their lives, some of them flew into Asian darkness, across primitive spaces of the mind and the land,

and came to terms with ancient fears the rest of us keep imperfectly at bay.

There was Steve Kusak. And poker-playing Roy Farrell from Texas. Saxophonist Al Mah, Einar “Micky” Mickelson, Jimmy Scoff,

Casey Boyd, Hockswinder, Thorwaldson, Rosbert, Maupin, and the rest.

And there is Captain Charlie Uban. Khaki shorts, no shirt, leather boots, tan pilot’s cap over wavy blond hair, gloves for

tightening the throttle lock. He waits in the darkness of northeast India for his clearance from air traffic control in nearby

Chabua. There are perhaps a dozen planes out there in the night, some of them flying with only 500 feet of vertical separation.

Captain Charlie Uban, Twenty-two years old, five feet nine inches, 141 pounds. Born in a room over the bank in Thompson, Iowa,

when airplanes were still a curiosity and the long Atlantic haul was only a dream to Lindbergh.

Chabua gives him his slot, and he powers his C-47 down the blacktop through the jungle night, riding like the hood ornament

on a diesel truck, with 5,000 pounds of small arms ammunition behind him in the cargo bay. He concentrates on the sound of

the twin Pratt & Whitney engines working hard at 2,700 RPMs, ignoring the chatter in his earphones,

The plane, with its payload plus 800 gallons of gasoline, is two tons over its recommended gross flying weight of 24,000 pounds.

Gently then, Charlie Uban eases back on the yoke, pulls the nose up, and climbs, not like an arrow, but rather in the way

a great heron beats its way upward from a green backwater.

It gets dicey about here. If an engine fails, he does not yet have enough air speed for rudder control. And he’s lost his

runway, so there is no opportunity to chop the takeoff and get stopped. But he gains altitude, turns southeast from Dinjan,

and flies toward that cordillera of the southern Himalayas called the Burma Hump.

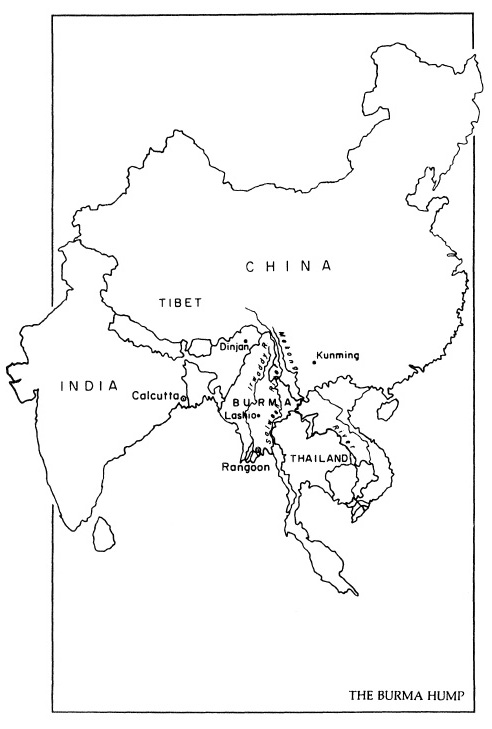

His copilot and radio operator are both Chinese. In the next four hours, they will cross three of the great river valleys

of the world: the Irrawaddy, the Salween, and the Mekong. In the place where India, Tibet, Burma, and Yunnan province of China

all come together, the mountain ranges lining these rivers constitute the Hump.

This is the world of the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC—pronounced “see-knack”). Jointly owned by China and Pan

American Airways, CNAC flies as a private carrier under nominal military control of the U.S. Air Transport Command. In the

flesh, CNAC is a strange collection of civilian pilots from the U.S., Australia, China, Great Britain, Canada, and Denmark.

They are soldiers of fortune, some of the best hired guns in the world at pushing early and elemental cargo planes where the

planes don’t want to go and where most pilots won’t take them. As one observer put it: “All were motivated by a thirst for

either money or adventure or both, and it was impossible to gain much of the first without acquiring a considerable amount

of the latter.”

Some were members of Claire Chennault’s dashing American Volunteer Group—the Flying Tigers—mustered out of various branches

of the U.S. military in 1941 to fly P-40 fighter planes with tiger teeth painted on the air coolers in defense of China. When

the AVG was disbanded, sixteen of the remaining twenty-one Tigers decided to throw in with CNAC.

Dinjan is the penultimate stop, the last caravanserai, on the World War II lend-lease column stretching from the United States

to Kunming, China. Along sea and air routes to Calcutta, and then by rail to Dinjan, moves virtually everything needed to

keep China in the war, including perfume and jewelry for Madame Chiang Kai-shek.

Japan controls the China coast and large slices of the interior. Until the spring of 1942, lend-lease supplies were shipped

to Rangoon, freighted by rail up to Lashio, and moved from there by truck over the Burma Road to China.

Then Vinegar Joe Stilwell’s armies, sabotaged by British disinterest in Burma and by the indecisive, fac-tionalized, and corrupt

government of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, were driven north. With the Japanese owning Rangoon, the railhead at Lashio,

and portions of the Road, China was closed to the outside by both land and water. So it fell to the pilots to ferry materiel

from Dinjan to Kunming. To fly the Hump.

As he reaches higher altitudes, Charlie pulls on a shirt, chino pants, woolen coveralls, and a leather flight jacket. Going

through 10,000 feet he switches over to oxygen. At 14,000 feet, he needs more power in the thin air and shifts the superchargers

to high. Above the Hump now.

In summer, the monsoons force him to fly on instruments much of the time. With winter come southern winds reaching velocities

of 100-150 miles per hour, and he crabs the plane thirty degrees off course just to counter the drift. Spring and fall bring

unpredictable winds, frequent and violent thunderstorms, and severe icing conditions.

He will fly over long stretches where there is no radio contact with the ground, up there on his own, blowing around in the

mountains without radar. “You had good weather information on your point of origin and your destination, and that was about

it,’ he remembers. The primary instruments in use will be Charlie Uban’s skills and instincts,

The winds push unwary or confused pilots steadily north into the higher peaks where planes regularly plow into the mountainsides.

And there are other problems. Ground radio signals used to locate runways in rough weather have a tendency to bounce from

the mountains. Even skilled and alert pilots mistakenly follow the echoes into cliffs.

Electrical equipment deteriorates from rapid changes between the cold of high altitudes and the tropical climate of Dinjan.

Parts are in short supply, navigational aids faulty or nonexistent. But maintenance wizards do what they can to keep the planes

rolling.

Pilots fly themselves into fatigue, sometimes making two round trips across the Hump in one day. Still they go, their efficiency

and competence shaming the regular army pilots in the Air Transport Command. CNAC, with creative, flexible management and

more experienced pilots, becomes the measure of performance for the entire ATC.

General Stilwell wrote in 1943: “The Air Transport Command record to date is pretty sad. CNAC has made them look like a bunch

of amateurs.” Edward V. Rickenbacker, chief of Eastern Airlines and America’s ace fighter pilot in World War 1, studies the

situation, discounts all of the army’s problems with airports, parts, and maintenance, and simply concludes that CNAC has

better pilots.

Charlie Uban is paid $800 a month for the first sixty hours of flying. He gets about $7 per hour, in Indian rupees, for the

next ten hours. For anything over seventy hours, he is on “gold,” $20 per hour in American money.

A 100-hour month earns him roughly $9,000 in 1987 terms. The rare melding of technical competence, practiced skill, good judgment,

and courage always pays top dollar, anywhere. The CNAC pilots chronicle their exploits by making up song verses using the

melody to the “Wabash Cannonball”:

Oh the mountains they are rugged

So the army boys all say.

The army gets the medals,

But see-knack gets the pay…

Not everyone can do it. They arrive as experienced flyers and are trained for the Hump by riding as copilots, committing the

terrain to memory, absorbing the mercurial techniques of high mountain flying, and practicing letdowns in bad weather. There

is no time for coddling. Those who can’t move into a captain’s seat in a few months are discharged. Charlie Uban got his command

in three weeks.

One veteran pilot makes a single round trip as copilot, is terrified, and asks to be sent home by boat. Others will hang on,

but are so intimidated by the Hump that they develop neuroses about it and become ill. Or, bent by their fears, they make

critical mistakes where there is room for none. The Hump, rising out there in the darkness and the rain, is malevolence crowned.

Was Charlie Uban afraid? He thinks about the question for a moment, a long moment, and grins, “I’d say respectful rather than

fearful.”

Fear and magic sometimes danced together in northern Burma. A Chinese pilot was flying a new plane from Dinjan to Kunming.

Over the middle of the Hump, the temperature gauge for one of the engines began climbing. The instructions were clear: “Feather

the engine at 265 centigrade.” Panic arrived at 250 degrees.

With a full load, a C-47 will fly at only 6,500 feet on one engine. So the choices were three. Feather the engine and descend to an altitude that is

not high enough to get through the mountains, let the temperature escalate and burn up the engine, or bail out in the high

mountains. Three alternatives, each with the same outcome.

But the manual had been written by Western minds. Therefore, and not surprisingly, the range of options was unnecessarily

constrained. As the gauge hit 265, the pilot broke the glass covering the gauge and simply twisted the dial backward to a

reasonable level Unable to get at the sender, he chose to throttle the messenger. There is some ancient rule at work here—if

you can’t repair the problem, at least you can improve your state of mind.

At Kunming, the gauge was diagnosed as faulty. The engine was just fine. Remember Kipling’s famous epitaph? “Here lies a fool

who tried to hustle the East.” The C-47, like a lot of others, tried and failed.

If a crew goes down in the Hump region, no search party is sent. The territory is wild and rugged, settled sparsely by aboriginal

tribes or occupied by the Japanese. The snow accumulates in places to a depth of several hundred feet, and a crashed plane

just disappears, absorbed by the snow.

The pilots suffer through it and gather strength from one another, talking quietly when a plane is overdue and cataloging

the optimistic possibilities. After a few weeks, the missing pilot’s clothing is parceled out among the others and his personal

effects are sent home.

Charles L. Sharp, Jr., operations manager for CNAC, is a realist. Roosevelt demands that China be supplied. There is not enough

time for proper training. The weather is wretched, equipment humbled by the task, and the planes, which are cargo versions

of the venerable DC-3s, always fly above the standard gross weight.

So lives are going to be taken. Sharp accepts that. Still, he grieves for the pilots who vanish out there in the snow or thunder

into foggy mountains during letdowns in China or blow up on the approach to Dinjan, and he worries about those who keep on

flying.

Small samples from his logs in CNAC’s war years intone a litany to risk and a chant of regret.

| Aircraft | ||||

| No. | Captain | Date | Location | Crew |

| 53 | Fox | 3/11/43 | Hump | Lost |

| 49 | Welch | 3/13/43 | Hump | Lost |

| 48 | Anglin | 8/11/43 | Hump | Lost |

| 72 | Schroeder | 10/13/43 | Shot Down | Lost |

| 59 | Privensal | 11/19/43 | Kunming:let-down | Lost |

| 63 | Charville | 11/19/43 | Kunming;let-down | Lost |

Between April 1942, when Hump operations started, and September 1945 at the end of the war, CNAC pilots will fly the Hump

more than 20,000 times. They carry 50,000 tons of cargo into China and bring 25,000 tons back out. Twenty-five crews are lost.

The consensus remains among those who understand flying that, given the conditions under which CNAC operated, the pilots were

one of the most skilled groups ever assembled, the losses remarkably small.

Today Charlie Uban is freighting ammunition. Sometimes he carries fifty-five-gallon barrels of high-octane gasoline, a cargo

he prefers not to haul Or he might be loaded with aircraft parts or medical supplies or brass fittings. Occasionally he moves

Chinese bank notes printed in San Francisco and being forwarded to deal with China’s sprinting inflation.