On Writing Romance (8 page)

Make sure the names you choose for your historical characters are appropriate for the time (many baby-name books list well-known people and help to date the origin and period of popularity of the name).

Watch out for objects and locations that haven't been invented or established by the time of your story, and beware of modern words, phrases, actions, and attitudes. A Regency hero carrying a briefcase or stopping at a hotel bar for a drink is the brainchild of an author who hasn't done enough research. A historical hero who tells the heroine to get a life is not believable, while a medieval heroine who worries about her self-esteem is an anachronism, since the concept of self-esteem is a twentieth-century one.

If in doubt about whether an expression is appropriate to the setting of your story, consult an unabridged dictionary that lists the first known use of a word or phrase. Slang dictionaries can also be helpful in creating dialogue that fits the historical period.

Another useful tool in writing about historical eras is an old encyclopedia. Encyclopedia Britannica's Web site (

www.britannica.com

) has a Classics section that shares articles from old editions. Britannica also has published replicas of some editions, including a 1771 encyclopedia in three volumes, which went into horrifying detail on subjects like childbirth and the medical treatments of the period.

Logic, consistency, and believability are key when dealing with scientific or pseudoscientific concepts such as other worlds, alien or futuristic societies, time travel, and superhuman characters. Imagination alone isn't enough. Without a solid foundation in reality, the author's alternate universe will not be convincing. There is no substitute for spending time in the classroom (or in equivalent study) to develop a comfort level with basic science.

The author of good science fiction has to be comfortable with the chemistry and physics of this world; then he can use known science as a launching point, following scientific principles and adding his own spin to create a world different from our own but equally logical and believable.

To create believable futuristic societies, it's wise to study past and current sociology, psychology, and political science, then project where past and current trends might logically lead.

If you base your characters' mode of travel to the twenty-third century (or the thirteenth century) on scientific principles, you'll have a much more believable scenario than if you just made something up. In addition, any sort of time-travel method has to be both logical and consistent to be convincing to readers. It isn't enough just to say that the elevator can become a time machine; you will need to explain to the readers how the heroine manages to summon the elevator in 1820 to take her home to 2010.

If you're writing about characters with supernatural powers, it's important to pay attention to legend and common understanding. Read the literature already out there. Your werewolf doesn't have to react exactly like the werewolves of legend, but if he doesn't, you'll need to account for the differences. If you simply ignore the common belief, your readers are likely to think you haven't done your research â and are apt to stop reading.

The more paranormal the world you're creating, the more necessary it is to have logical explanations for everything that happens. Because your readers will be paying closer attention than usual as they try to figure out the rules of your universe, they're more likely to notice if you slip up and violate your own logic or laws.

Once you set up a rule for your world, that rule becomes like a law of physics and you have to live with it â the rule can't come and go depending on how convenient it is to the plot. Once you've set up the conditions that make your time machine work, you can't have it stop working under those same conditions just because you don't want the heroine to time-travel at that exact moment. If your vampires need to seek out a victim with a matching blood type, then you can't later have them ignore that rule unless you have a convincing explanation for why it's no longer necessary.

Sometimes you'll know your material cold â and you'll be absolutely correct â but your readers' previous experience disagrees. You may know there were cattle drives in sixteenth-century Scotland, but your readers are equally sure you must have been thinking of Texas instead. You may know that in big-city children's hospitals, neonatal doctors work regular shifts and are never more than thirty seconds away from a preemie's incubator. But your readers in West Podunk, where there's a ten-bed hospital and one pediatrician on call in the next county, can't imagine it. It's not much comfort to be right if your readers toss the book aside because they're convinced you're talking through your hat.

In cases like that, the burden of proof lies with the author. You not only have to show the cattle drive or the neonatal doctor, you have to convince the readers that you know what you're talking about. You can do that by making the picture so plain that it's impossible not to believe you. Or you can do it by bringing up the doubts yourself â maybe have a visitor in the neonatal unit ask how long it will take to get a doctor â which gives you a reason to explain.

Your readers may still think you're making it up, but at least they'll know you didn't create the scene out of ignorance.

N

R

EVIEW

: Planning Your Research Strategy

Look back at the romance novels you've been reading. What aspects of the stories do you think the authors needed to research?

Where might they have found the information they drew on to write the books?

What research sources will you need to consult before you're ready to begin writing?

What sources might be helpful during the writing process?

Establishing Your Framework

Essential Elements

Even if you're a seat-of-the-pants, explore-as-you-go sort of writer, there are a few things you need to know about your story before you start seriously writing chapter one. Unsuccessful romances â especially the many that writers start but never complete â stall out because the writer didn't know enough about the basic framework that holds every romance novel together.

Though it's nearly impossible to have every detail worked out ahead of time, if you don't have a pretty good idea of your framework, you'll be apt to wander in frustration with a story that goes nowhere. Or you'll write chapter one over and over, trying to make it work, until you're heartily sick of your characters.

So what are the basics you need to know up front?

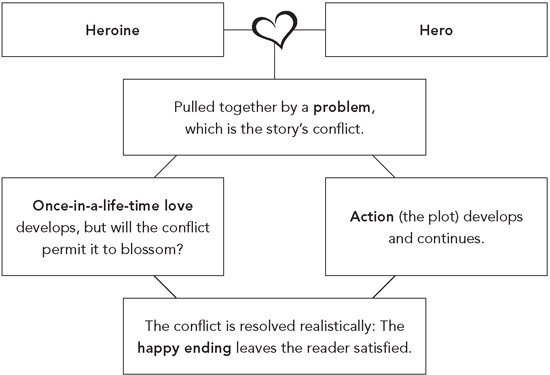

Let's review the definition we established for the romance novel: A romance novel is the story of a man and a woman who, while they're solving a problem that threatens to keep them apart, discover that the love they feel for each other is the sort that comes along only once in a lifetime; this discovery leads to a permanent commitment and a happy ending.

This definition summarizes the four crucial basics that make up a romance novel:

a hero and a heroine to fall in love

a problem that creates conflict and tension between them and threatens to keep them apart

a developing love that is so special it comes about only once in a lifetime

a resolution in which the problem is solved and the couple is united

These things are the girders that hold up your entire story. Like the steel skeleton of a skyscraper, each piece depends on the others. If one is weak or flawed, the whole structure is apt to fall down.

What your hero and heroine have experienced in their pasts will influence how they react to the problem they face in your story. The nature of the conflict between them will influence their relationship and how the sexual tension develops. The traits that make this couple fall in love will influence what the happy ending will be. If the conflict has no satisfactory resolution, it's not going to be a truly happy ending, even if the hero and heroine fling themselves into each other's arms on the last page.

Knowing the basics up front will keep you from reaching the middle of the book with a limp conflict, no sexual tension, and two characters who have absolutely no reason to want to be together.

Without two people to fall in love, there is no story. Since you're asking readers to spend several hours with your characters, it's important to create a hero and a heroine they want to know more about. That means the characters have to be both real (so readers can relate to them on a human level) and sympathetic (so readers feel the time they spend reading the characters' story is worthwhile).

If the readers spend several hours reading the story, most of that time will be in the company of the heroine. So your heroine must be someone the readers can understand, like, and respect â someone they want to hang around with. Someone who seems like a real person.

The hero must be someone the readers can picture themselves falling in love with. But you want them not just to fall in love with him â experiencing that dizzying, glorious rush of emotion â you want them to

stay

in love with him and believe that the heroine will be truly happy with him forever.

The next chapter, which goes into detail about heroes and heroines and how you can develop your main characters, may be the most important chapter in this book. If your hero and heroine don't come to life for your readers â if they aren't people they care about, root for, and want to be happy â they're not likely to spend their precious time reading a book about them.

Knowing your characters is extraordinarily important. If you don't know these people almost as well as you know yourself, then how will you know how they would react to the problems you've created for them â or to each other? You will sometimes hear an author say something like, “I wanted my heroine to be shaken up by the bad guy making a pass at her, but she just rolled her eyes and said, âYeah, right, like

that's

going to upset me.' So I had to figure out another way to make her turn to the hero for help.”

Your reaction might be to wonder if the writer is having a hallucination. After all, the writer creates the character â so how can the character simply refuse to cooperate? What the writer is really saying is that she created a character so believable â so real â that she knows how that person would act or react in a given situation. When she then tries to write a situation that is inconsistent with the character's values or personality, the character just won't go along with the plan.

Chapter four will go into more detail about creating real, sympathetic, believable characters â the first requirement for your romance novel.

While the developing relationship between the hero and heroine (which we'll address next) is at the center of the story, it is not the entire story. If the main question in a romance novel is simply whether and when the hero and heroine will admit they love each other, then the story will be unsatisfying. Readers know from the beginning that they will, because they're reading a romance. Watching two people date, get to know each other, and slowly explore their growing attraction isn't terribly exciting.

It's the difficulties that surround

this

couple falling in love at

this

moment â the difficulties that threaten to keep them from reaching a happy ending â that keep the readers' attention. The way in which these difficulties impact these particular characters, putting pressure on them and bringing out their good points and their flaws, is what makes their story exciting.

That's the main way in which romance novels differ from real life â in real life, most of us prefer a calm and peaceful period to get to know each other. But calm and peaceful don't make a gripping book. It's the tension between the characters, caused by the problems they face, that makes the story exciting and unforgettable.

Tension between the characters is conflict, the second of our important framework pieces.

In the excitement of creating your hero and heroine and developing your story, it's easy to confuse plot with conflict. The

plot

is what happens while your two characters are falling in love; it's simply the sequence of events.

Conflict

is the difficulty between the hero and heroine that threatens to keep them from getting together. It arises because of the problems the characters face.

Most romance novels have two types of conflict: the short-term problem and the long-term problem. The short-term problem (sometimes called the

external conflict

) revolves around the initial situation that brings the couple together and keeps them together so they can get to know each other. The long-term problem (sometimes called the

internal conflict

) is the deeper difficulty each character faces â the difficulty that threatens to keep the couple from finding happiness together.

In many beginners' stories, the hero and heroine have plenty of problems. He's having trouble with his business; she can't get along with her father; he's got custody issues; she's in debt. But unless these problems cause tension between them, there's a shortage of conflict in the story.

The hero and heroine don't have to be at each other's throats all the time. In fact, it's better if they aren't always disagreeing. But if they agree on everything, if their relationship is calm and peaceful, then what's keeping them from recognizing and admitting they're in love?

On the other hand, if they can't get along, why doesn't one or the other just walk away? Why can't they avoid each other?

Chapter five will investigate conflict in depth â what it is and isn't, and how to develop realistic and believable conflict.

The need for a romance in a romance novel seems so obvious. After all, the romance novel is a love story â the hero and heroine

have

to fall in love. But if you stop and think about it, this important aspect is trickier than it first appears.

It's easy to write in a synopsis, “As they get to know each other, they fall in love.” But showing that love growing is an entirely different proposition. If it happens too quickly, the readers will be bored. If it happens too slowly, the readers won't believe the happy ending.

Each event in the story helps your lovers see each other differently, discover new traits (good and bad), and get to know each other on a deeper level.

It's much easier to focus on action or to detail the bad guy's plans than it is to portray, step-by-step, the slow flowering of a caring relationship. As you develop the framework of your story, keep in mind the importance of the characters' reactions to each other. What events will best allow each to see new aspects of the other's character? What is there about each person that causes them to fall in love? What makes this couple so perfect for each other (even though it doesn't appear that way at first) that their love story will remain in the readers' minds forever?

Chapter six will go into more detail about the once-in-a-lifetime love, the third pillar of the successful romance.

How is your story going to end? I'm not suggesting you have to know every detail â before you start writing â about how your characters solve their difficulties and live happily ever after, but it pays to have a good idea. Having your destination in mind makes the journey easier.

And if your book is to be a romance novel, then the story must finish with a happy ending â a positive, upbeat, hopeful resolution, which in most cases will involve a permanent commitment between the two main characters.

As you're thinking in terms of framework, you don't have to know your characters' street addresses or how many kids they end up having, but do look hard at any big issues you've raised. If your characters' conflict has involved their lifestyles (he loves the country, she wants the excitement of the city), will they compromise or will one of them give in? If he hates her job, how do they resolve the problem so both can be satisfied? If she's had trouble trusting him, how does he prove himself (or how does she convince herself he's trustworthy now)?

The most important thing about the resolution is that the issues â big and small â that have separated the characters are settled in a way that is logical and satisfying to the readers. Each issue is handled rather than avoided; the solutions are plausible and fitting for the situations and the characters, so the readers can believe that this agreement will last and will continue to be acceptable to both main characters. A satisfying ending comes about because of the actions of the characters themselves, not through the interference of others.

Chapter six will go into more detail about planning the resolution of your conflicts and deciding how the issues you've raised between your characters will ultimately be resolved.

You may not be ready to put on paper all the ideas for your hero and heroine, conflict, once-in-a-lifetime-love, and happy ending. After all, you've just started to find out why these things are important to your story.