One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power (60 page)

Read One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power Online

Authors: Douglas V. Smith

Â

9

.

Â

U.S. Navy LSO School,

http://www.robertheffley.com/docs/CV_environ/Basic%20IFLOLS%20Lecture%5b2%5d.ppt#259,3,From Paddles to IFLOLS

(accessed 15 August 2009).

Â

10

.

Â

Major Richard A. Bauer, USMC, and Lieutenant Leo L. Hamilton, USN, “Naval Aircraft Maintenance Program,”

Naval Aviation News

, February 1961, p. 25.

Â

11

.

Â

Ibid., p. 28.

Â

12

.

Â

Richard A. Eldridge, “A Look Back: Forty Years of Reminiscing,”

http://safetycenter.navy.mil/media/approach/theydidwhat/eldridge.htm

(accessed 24 March 2009).

Â

13

.

Â

Jerry Miller,

Nuclear Weapons and Aircraft Carriers

(Washington, DC: The Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), p. 104.

Â

14

.

Â

Steve Ewing,

Reaper Leader

(Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2002), pp. 198â99.

Â

15

.

Â

“The One Best Way, New Standards for Naval Air,”

Naval Aviation News

, August 1961, p. 6,

http://www.history.navy.mil/nan/backissues/1960s/1961/aug61.pdf

(accessed 28 May 2009).

Â

16

.

Â

Oral history of Rear Admiral Thomas F. Brown III, conducted by Joseph Smith, 5 March 2002 to 24 March 2002. Naval Historical Foundation Oral History Program, 2004.

Â

17

.

Â

O'Roarke, “We Get Ours at Night,” p. 26.

Naval Aviation in the Korean and Vietnam Wars

Gary J. Ohls

THE KOREAN CONFLICT

O

n Sunday, 25 June 1950, the North Korean People's Armyâthe

In Min Gun

âattacked across the 38th parallel into the Republic of Korea (ROK) thereby initiating the Korean War.

1

Numerous provocations over the preceding two years such as raids, sabotage, guerrilla activity, infiltration, propaganda, and economic pressure had failed to bring down the Syngman Rhee government or persuade a majority of South Koreans to support a Communist takeover.

2

Meanwhile, the United States had sent ambiguous diplomatic signals regarding its commitment to Korea, and all of Asia for that matter, beyond its vital interests in Japan and the Philippines.

3

The general weakness of American military forces in the Far East coupled with their withdrawal from Korea after the establishment of the Rhee government in 1948 created an impression among Communist leaders that a conventional assault from the North could succeed where numerous subversive efforts had failed.

4

Additionally, the 1949 Communist takeover of mainland China had reinforced the notion that America would not commit ground forces on the mainland of Asia.

5

The United States had stood by as Mao Zedong's Communists forces defeated the Nationalist Chineseâan America ally throughout and after World War IIâand drove them to the island of Formosa (Taiwan), at some cost to America's international stature.

6

In light of all these considerations, Communist leaders in Pyongyang, Beijing (Peking, as it was then called), and Moscow believed attacking South Korea would be a relatively low-risk operation, which could produce great strategic advantages throughout Asia.

7

During the months leading up to the North Korean attack, U.S. intelligence services observed increasing signs of its possibility, yet the actual event achieved strategic and tactical surprise.

8

Despite the fact that many ROK units and individuals fought courageously and in some cases effectively, their weapons, equipment, training, and leadership could not match that of the North Korean People's Army (NKPA). The ROK Army had no armor to oppose the T-34 tanksâprovided to North Korea by the Soviet Unionânor did they possess antitank weapons capable of stopping them.

9

They had no heavy artillery comparable to the Soviet-supplied systems, and did not have fighter planes or antiaircraft weapons with which to oppose North Korea's Soviet-supplied aircraft.

10

When coupled with the element of surprise, these deficiencies proved far too great to overcome.

11

The blatant nature of the North Korean attack supported by weapons, material, and training from the Soviet Union caused many American leaders to see a similar pattern in which “Hitler, Mussolini and the Japanese had acted ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier.”

12

In the days immediately following Kim Il-sung's invasion of the Republic of Korea, important events took place in New York and Washington D.C. The United Nations passed a resolution that condemned the attack as an act of aggression, ordered North Korea to cease operations and withdraw its forces, and called on member nations to assist the United Nations in resisting the action.

13

The Soviet delegation would surely have blocked this resolution had they not been boycotting Security Council meetings at the time, in protest against its refusal to seat the People's Republic of China.

14

Ostensively the war in Korea would be fought under the auspices of the UN; but in essence, it would be an American conflict despite the small contribution of a few allies.

15

The UN action provided the Truman administration a certain amount of international and domestic cover, allowing the United States to take action that might otherwise be problematic.

Among other things, the president of the United States ordered General Douglas MacArthur to take command of all U.S. forces in Korea, conduct evacuation of American citizens, provide ammunition and equipment to South Korean forces, and move the U.S. Seventh Fleetâunder command of Vice Admiral Arthur D. Strubleânorth from the Philippines. He also authorized the use of air and naval forces to protect all such activity and for a survey team to evaluate the situation on the peninsula and determine what the United States could do to assist the Republic of Korea.

16

The president expanded MacArthur's area of responsibility to include Formosa and ordered the Seventh Fleet to protect that island nation against attack from Communist China.

17

In addition to defending Formosa, Seventh Fleet would also inhibit Chiang Kai-shek from using the crisis as a pretext to attack mainland China, thereby expanding the war.

18

The earliest American combat action of this conflict involved an effort to keep open the air and sea points of embarkation for emergency evacuation. When North Korean YAK fighters attacked U.S. Air Force

F-80 Shooting Star and F-82 Twin Mustang aircraft covering the evacuation of civilians over Inchon, American pilots splashed three of the Communist aircraft and later shot down four more over Seoul.

19

Despite the unpreparedness of U.S. forces, President Harry S. Truman believed he must prevent a Communist takeover of South Korea even if it meant going to war.

20

In Truman's view, this crisis constituted a critical test of will between the two international blocksâfree democracies and totalitarian Communismâthat had evolved since the end of World War II.

21

It was a decision widely supported at the time by the American people and the U.S. Congress.

22

Within days of the North Korean attack, the Truman administration authorized MacArthur to use American ground forces to halt the North Korean advance.

23

Of course, this would be problematic since the United States had chosen to scuttle its military might in the aftermath of World War II.

24

Ultimately, it would take full application of American air, naval, and amphibious capability as well as the activation of four National Guard divisions and numerous reserves to reverse the fortunes of war in Korea.

25

Carrier-based naval air power along with land- and carrier-based Marine Corps close air support would prove crucial in the hard fighting American forces faced during three years of the Korean War.

26

American planes of the Far Eastern Air Forceâunder command of Lieutenant General George E. Stratemeyerânot only engaged North Korean YAKs during evacuation operations at Inchon and Seoul, but also conducted some to the earliest offensive actions of the Korean War. B-29 Superfortresses and B-26 Invaders flew missions against targets in North Korea, andâin conjunction with F-80 Shooting Starsâattempted to provide support to allied ground troops in the South.

27

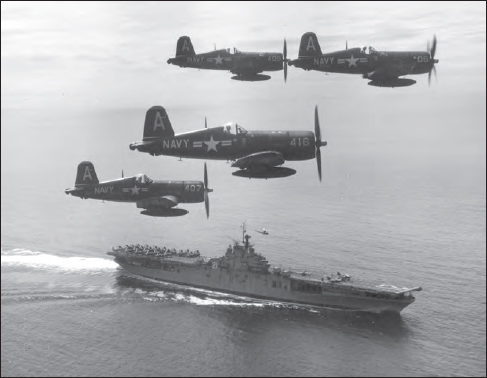

The U.S. Navy also conducted early offensive action with the first major strike coming from aircraft of Seventh Fleet's Task Force 77 off USS

Valley Forge

on 3 July 1950. These carrier planes, consisting of F9F Panthers, F4U corsairs, and AD Skyraiders, attacked the North Korea capital at Pyongyang and other targets, destroying much of the North Korean air force in the process.

28

Throughout the month of July, Task Force 77âincluding the Royal Navy's HMS

Triumph

and several British escortsâattacked enemy targets in both North and South Korea, while Task Force 96 (a surface action group consisting of one cruiser and four destroyers) provided naval gunfire in support of South Korean forces retreating down the peninsula toward Pusan.

29

The F-80 Shooting Star served as the preeminent U.S. Air Force plane in the theater at that time, but it was primarily a fighter-interceptor. Although superior to anything the North Koreans had, these planes were not ideal in the ground support role. Additionally, they primarily flew out of bases in Japan carrying limited ordnance loads due to their fuel requirements. Therefore, they had minimal time on station once they arrived over Korea. As a result, the only substantial air support available to U.S. and ROK ground forces during much of the early fighting came from carrier-based tactical air.

30

The outbreak of the Korean War found the United States near the nadir of its postâWorld War II disarmament. Although the National Security Act of 1947 and its addendum of 1949 purported to strengthen the U.S. military, they fell far short of that goal. Besides, even the most effective legislation could not have overcome the severe budget reductions imposed on the military by Congress and enthusiastically carried out by the Truman administration.

31

Of course, this created enormous inter-Service rivalry for resources, roles, and missions.

32

Additionally, the newly formed U.S. Air Force had made a disruptive play for control of all air missions during the postwar unification battles, including those developed and performed by naval aviation.

33

Many leaders within the defense establishment questioned the need for carrier-based air power anyway, believing that land-based bombers could assume all Navy missions. Secretary of Defense Louis A. Johnson had ungraciously stated to Admiral Richard L. Conolly just six months before the Communist invasion of South Korea, “Admiral, the Navy is on its way out. . . . There's no reason for having a Navy and Marine Corps. General [Omar] Bradley tells me that amphibious operations are a thing of the past. We'll never have any more amphibious operations. That does away with the Marine Corps. And the Air Force can do anything the Navy

can nowadays, so that does away with the Navy.”

34

Johnson underscored his myopic view of defense planning by canceling the Navy's modern super carrier project, USS

United States

, and promoting a strategic bomber of questionable design and excessive cost named the B-36 Peacemaker.

35

The subsequent B-36 debate and controversy had the unfortunate effect of focusing the Air Force's thinking primarily on strategic air power at the expense of tactical capability.

36

To the extent that naval aviation continued to develop in the constrained and conflicted environment of the late 1940s, it did so in an era of technological change, including the transition from propeller to jet propulsion and the consequent need to move toward more capable carriers.

37

By 1950, cost-cutting measures had programmed the Navy to retain only five fleet carriers despite the clear beginnings of a Cold War with the Soviet Union. Of course, the U.S. government had mothballed large quantities of ships and other combat systems at the end of World War II with the intention of refurbishing them for future wars, if and when necessary.

38

In the event, nineteen enhanced

Essex

-class carriers eventually returned to service by the end of the Korean War, fully equipped with operational air groups. This revitalization of naval aviation permitted four carriers to operate continuously in Korean waters while maintaining two in the Mediterranean in support of NATO strategy through the end of the war. Despite Secretary Johnson's arrogant claims of the demise of the Navy and Marine Corps, carrier aircraftâunder Navy and Marine Corps leadershipâflew more than 30 percent of all combat sorties of the Korean War.

39

This naval air power, coupled with land-based Air Force capability, proved essential to American operations against the vastly superior manpower that the Chinese Army brought to the fighting when it entered the war in the final months of 1950.